The first-ever death of a Tesla driver on Autopilot sparked journalistic mayhem: Spectacular, 1,000-word pile-ups of fear-mongering and finger-pointing.

Of course Americans are worried about self-driving cars. They don’t understand the cars they drive today. And automotive technology makes them anxious, a mindset exploited by cynical, sensational reporting on anything carrying a whiff of scandal: Volkswagen cheated on diesel testing; your children will soon die of asthma. Takata airbags are defective; get ready for a face-full of shrapnel on your morning commute.

Combine an electric Tesla (already mysterious to many people) with the specter of self-driving cars – which conjure images of unintended acceleration or terrorist hackers – and you have a perfect storm of technophobia and misinformation. I’m already girding myself for a bogus Dateline NBC expose of some runaway Tesla, with ominous music and a fine sprinkling of paranoia.

So it’s vital that consumers recognize a few things: The self-driving future may seem wondrous, upsetting or both, but the cars themselves aren’t magic. The building blocks of self-driving technology have been around for nearly 30 years, meaning the car you drive today likely has some semi-autonomous features. Even in rudimentary form, that technology is already reducing real-world accidents, injuries and by extension fatalities. As our Alex Roy has noted, it all argues for full-speed-ahead development of autonomous cars that could save tens of thousands of lives a year in America alone.

That revolution will take years and mistakes will be made, though the carnage on the world’s roads will decline until we shake our heads in wonder at our old, primitive ways – as we do when we recall riding in cars with no seat belts or protections of any kind.

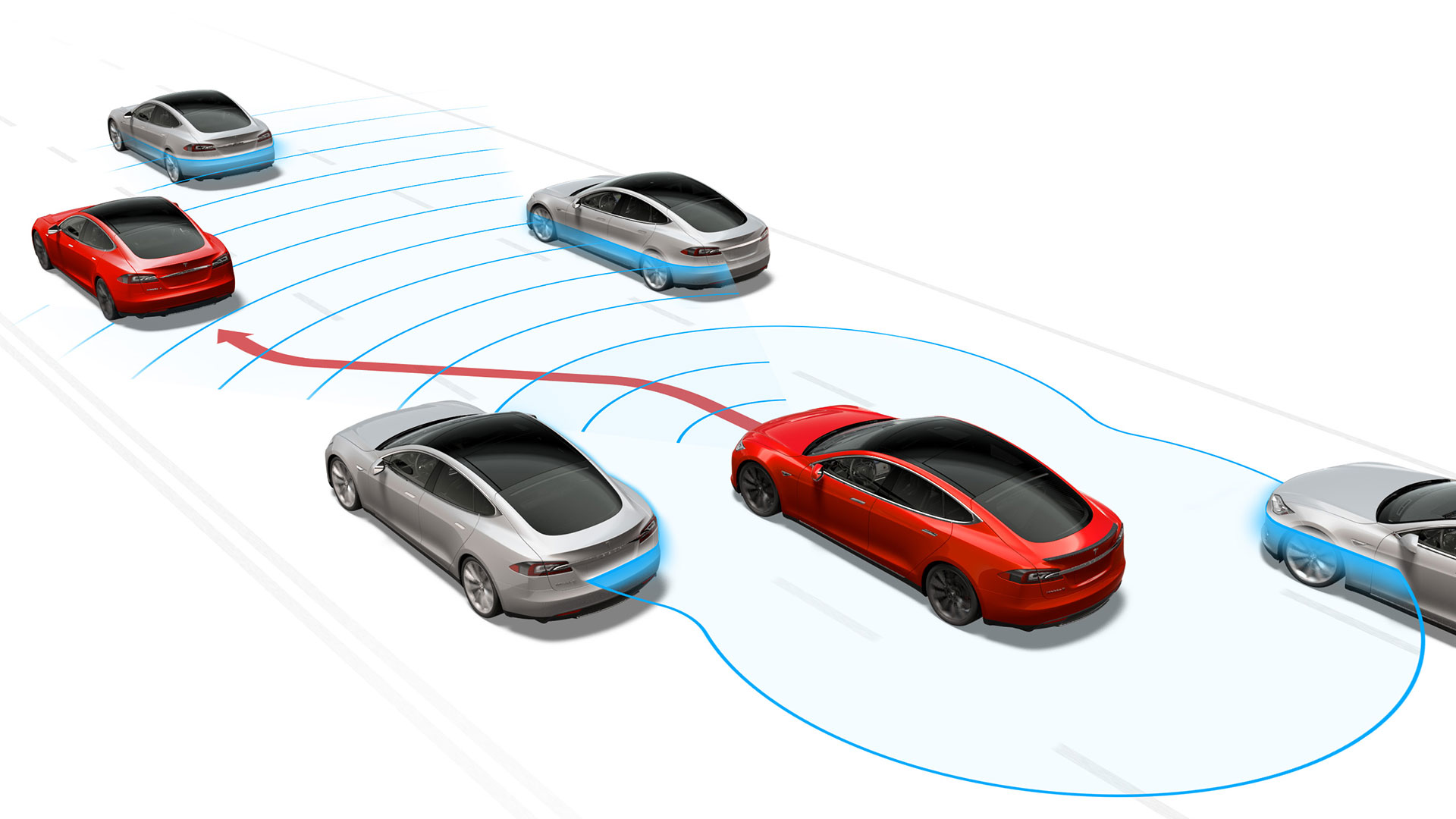

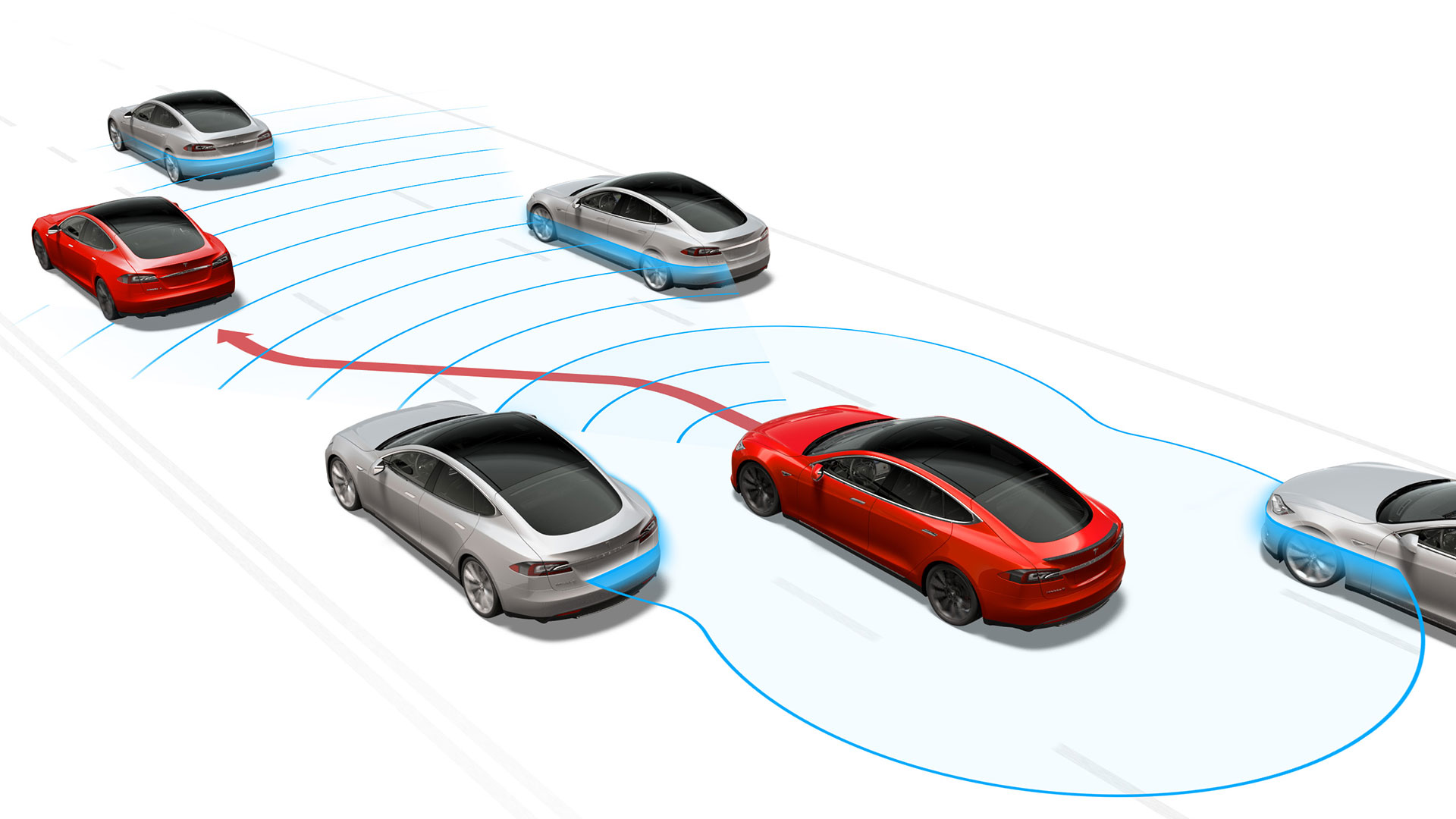

But make no mistake, that revolution has begun, and it traces not to Tesla but to Mercedes, BMW, General Motors and others. Beginning in the late ‘80s, traction and stability control systems began monitoring cars’ movements and adjusting the throttle or brakes to avoid wheelspin and potentially deadly spins. Those systems are nearly universal on today’s showroom cars. Mercedes introduced its radar-based Distronic adaptive cruise control on the S-Class in 1999, the first car that could identify cars ahead, and brake or accelerate on its own to pace traffic. That rudimentary feature, the ability to follow cars nose-to-tail like a line of stable horses, remains the basis of every semi-autonomous system, including Tesla’s.

Showroom successors have added a fairly modest batch of features since: To alert drivers that they’re drifting from their lane; to brake with near-maximum force to avoid cars, people or large animals; and only recently to steer along gentle highway curves within a well-marked lane. Without a rabbit leading it, or blocking its path, even Tesla’s Autopilot would drive straight through an intersection stop sign or red light. Its cars can’t handle 90-degree turns, or deal with sharper, speedier corners on typical two-lane roads.

That’s the most disturbing thing about the accident that took ex-Navy Seal Joshua Brown’s life: His Tesla Model S failed at its most basic task, the assurance that you won’t smack the object in front of you. The accident revealed a literal blind spot in the Tesla system, despite the driver’s shared responsibility in failing to see and react to a looming threat. None of this is reason to stop technical progress in its tracks.

That’s because the semi-autonomous features becoming common on affordable cars – forward collision warnings and automated braking – are already showing the fruitful, life-saving path ahead.

Cars with automated front crash prevention systems are piling up enough data to show significant real-world safety gains. According to one influential safety watchdog, the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, cars with automated front crash prevention systems are seeing up to 35 percent fewer claims for bodily injury. The IIHS based that research on nine systems from five manufacturers, including Volvo, Subaru and Honda. Claims for collision and other property damage are falling as well. It’s too early to judge fatalities, however, because systems like Volvo’s City Safety are mainly avoiding or mitigating injuries and damage in lower-speed, around-town collisions.

That said, “These systems are preventing front-to-rear crashes in everyday traffic,” says Adrian Lund, IIHS president. “We know there’s going to be benefits, but we don’t yet know the full extent,” Lund says.

Automakers aren’t waiting to find out. In March, spurred by the IIHS and the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 20 automakers voluntarily agreed to make automated emergency braking standard on all new cars by Sept. 1, 2022. It’s an extraordinary consensus, representing 99 percent of the new cars on American roads. And it shows how much confidence automakers have in technology that they’ve been developing and refining for at least two decades.

Some naysayers of semi-autonomy, including Consumer Reports’ would-be takedown of Tesla’s Autopilot, are already working from a familiar playbook. They’re suggesting that drivers en masse will gain a false sense of security, or take reckless chances behind the wheel. The same arguments were levied against anti-lock brakes, air bags, and even seat belts. but they’ve got it as backwards as ever.

Certainly, a self-driving car is different from a seatbelt. In a recent late-night Interstate drive in an Audi Q7.

I was relying on its own semi-autonomous system when a deer popped up from the ditch and made me jump out of my skin. Sure, that happens to drivers all the time. But I realized I was less prepared to take evasive action than usual, having let the Audi largely do the driving for an extended period.

Distraction is an issue, the IIHS’ Lund says, including that tricky netherworld where a car can’t handle a certain situation and asks the driver to quickly reassert control. Even without a robot co-pilot, driving can be a near-automatic task, he says, as in those times when you pull into your driveway and realize you don’t remember how you got there.

“Your brain is only going to put as much into the task as required. The more the vehicle does for you, the less attention required. So your mind wanders,” Lund says.

Fortunately, some early research suggests that forward collision and lane-departure monitors don’t make drivers pay less attention or take on secondary tasks, such as things like checking text messages. Those studies haven’t yet dealt with more-advanced systems that manage steering, speed and braking, according to Lund.

More research is needed. But to claim that human inattention or irresponsibility makes semi-autonomy unsafe is like trying to ban seat belts because some idiot will always refuse to buckle up.

Regarding the tragic Tesla accident, Lund says that a semi-trailer blocking the highway is a situation that could flummox many drivers.

“When you’re driving, you’re putting situations into mental categories, but here’s a category it doesn’t really have, a trailer across the entire road,” Lund says.

In this case, both Tesla’s Autopilot and the daydreaming pilot were flummoxed. And Lund says improved systems might identify intersections or other potential hazards and cue drivers to be more vigilant.

“If there’s one thing we learn from this, it’s that there may be special situations you need to be alerted to,” Lund says “Situations where extra caution is needed, where the system rings a chime or whatever to bring the driver back.”

“The key is to make sure that, where you can take your hands off the wheel, the system only allows that where you’re very confident you’re not going to run into something unexpected” he says.

Yet Lund notes that 100 drivers a year plow into a semi that’s sideways across the road, often under-riding its trailer. Roughly half of those crashes occur in broad daylight. In other words, people manage to drive straight into the sides of trucks with no help or hindrance from an Autopilot. In the vast majority of crashes, the human remains the weak link in the chain. When it comes to semi-autonomous cars, the only thing to fear is us.