This aquatic Knifefish robot can’t do flips, squeak or save a floundering swimmer, yet it is this shiny little water dagger that will soon replace the U.S. Navy’s pod of highly-trained and adorable dolphins and seals. As with so many things these days, flesh, bone and feeling are being replaced with crisp autonomy. That manual-transmission Ferrari that you worked towards for 30 years? No more—Ferrari’s intelligent dual-clutch transmission will do the work for you. The 2030 road trip you planned to take for that milestone birthday? Maybe bump it up to ensure that human-driven vehicles, not just autonomous Google pods, are still legal on the highways.

Now, that creeping tide of self-sufficient bits and bytes has flooded the Navy, which will shortly evict its mammals in favor of an electric, computerized torpedo: In two years, the Navy’s Marine Mammal Program will end, putting dozens dolphins, sea lions and even beluga whales out of work. For the first time in the better part of a century, America’s illustrious military will count no cetaceans among its ranks. For that, we’re sad.

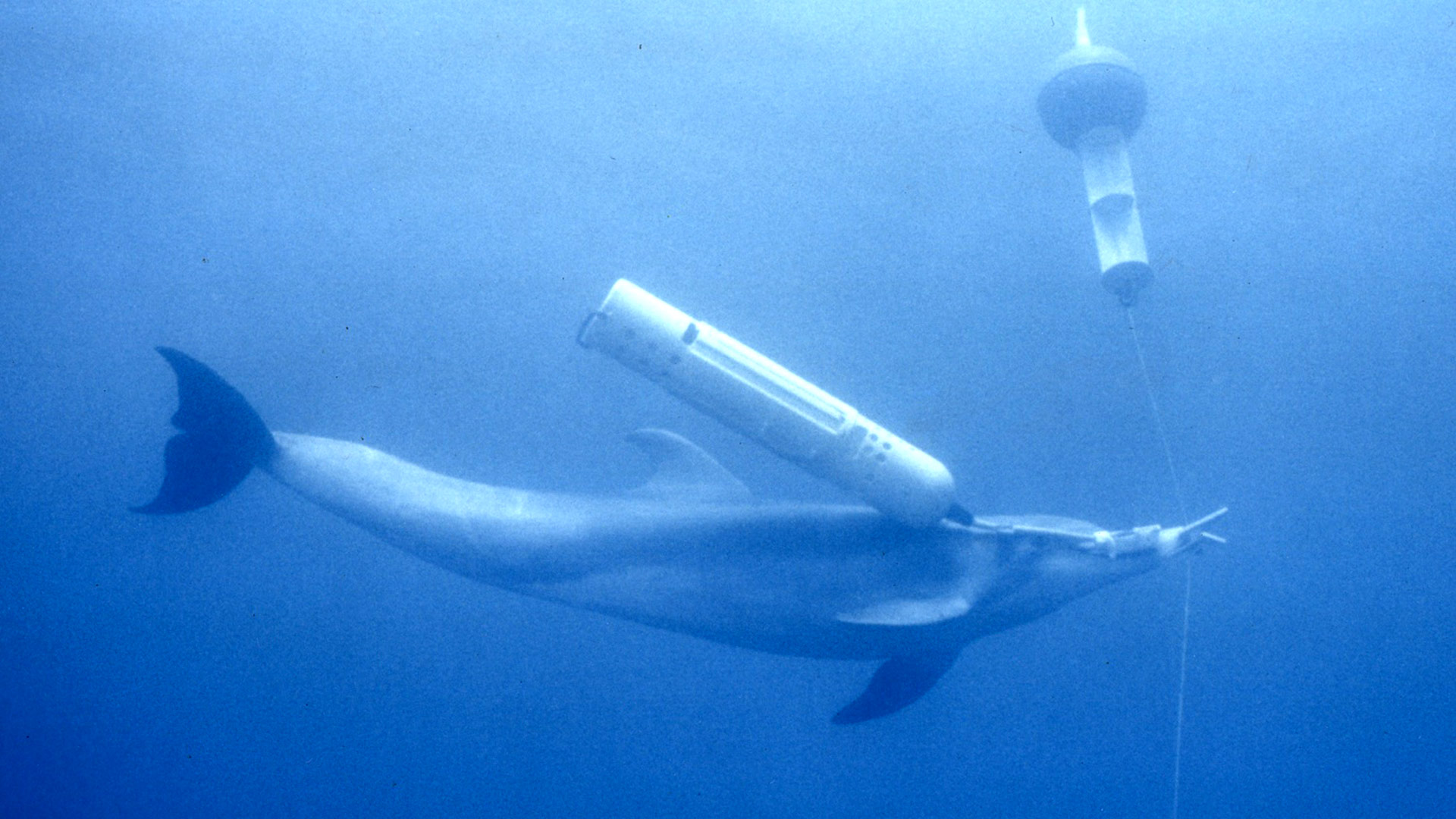

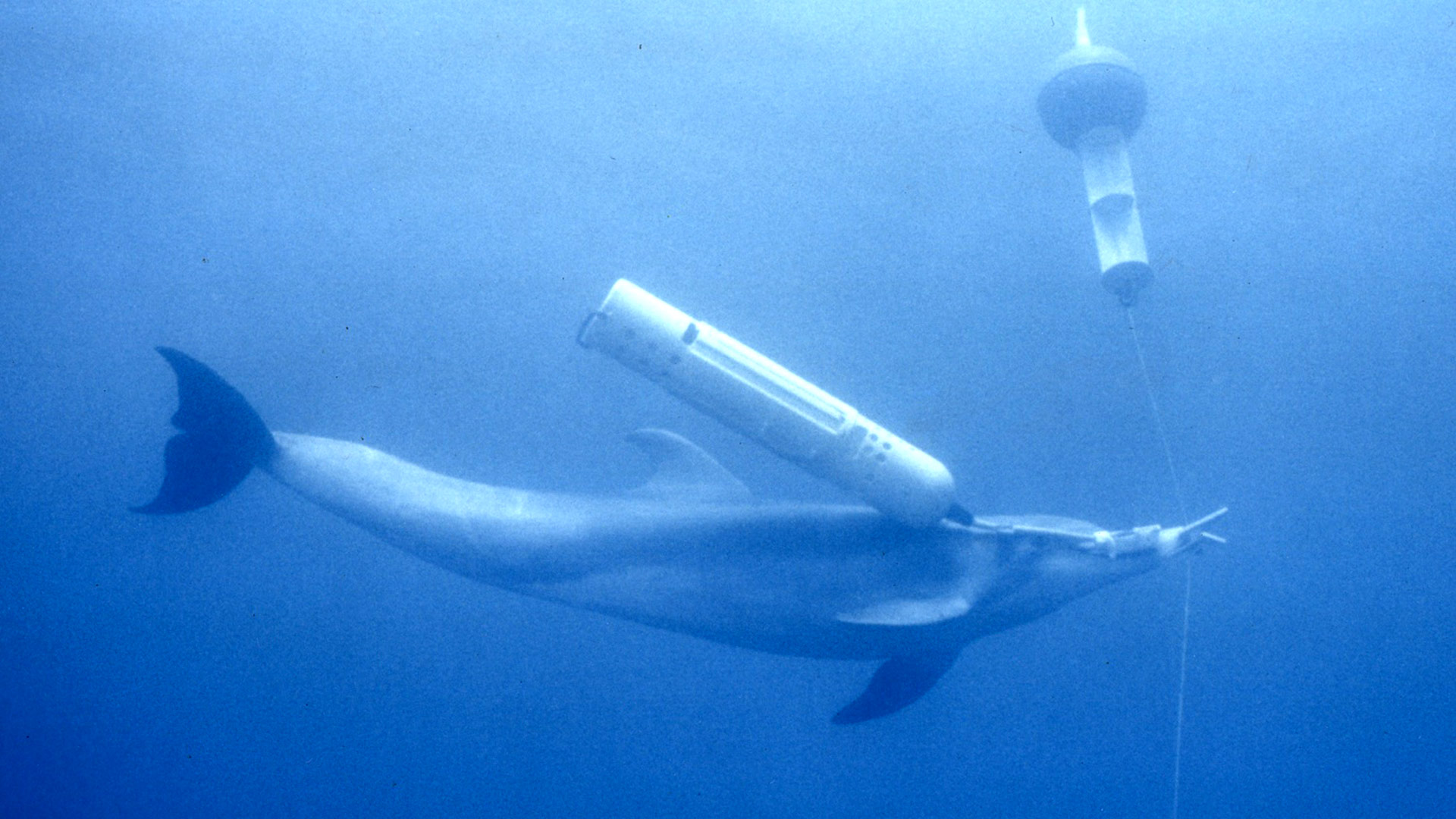

The earliest iteration of the military’s use of sea mammals came in 1960, when a single Pacific White-Sided Dolphin was used by the Navy to research the hydrodynamic properties of the animal’s skin and shape for use in missile production. In working with that dolphin, handlers realized that the animal’s intelligence, trainability and agility could make them invaluable. Dangerous operations like mine-hunting, object retrieval and the flagging of enemy swimmers or subs had, to that point, been undertaken by human divers. Sea lions soon replaced soldiers in boats as sentries in many Navy harbors, though they did not wear hats.

After capturing and training more dolphins and sea lions, the MMP became a classified, black budget program. (Yes, dolphin spies.) In 1967, a training and care facility was set up in Point Loma, San Diego; since then, the animals have been used in combat during the Vietnam and the Iraq Wars, though not specifically, the program is careful to note, in combat roles. The 140 animals at Point Loma can be deployed within 72 hours.

But that will all change come 2017, when the General Dynamics Knifefish arrives. It is a propeller-drive, mine-sweeping robotic torpedo just under 20 feet in length—menacing, in a way even a harbor seal with a camera on its flipper is not. Like a Tesla, the Knifefish uses lithium ion batteries, and can dive for up to 16 hours without a charge. SONAR, a less-sophisticated version of what the dolphins used, detects naval mines and records their location in a database. Littoral combat ships, from which the Knifefish is deployed, then upload the information and destroy the mines. Last year, a Knifefish prototype was used in the search for Malaysia Airlines flight 370. It’s combat readiness, though, has yet to be tested.

Should things, in two years, go south, we will be the first to call for a Red-style reassembly of the mammalian defense pod. Because, while electric torpedoes are cool, dolphins are our brothers in the sea. And now, the latest victims of automation.