We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn more ›

The ingratiating headline should have told me to avert my eyes. But like a bad car crash, I had to look: “Driverless cars made me nervous. Then I tried one,” read the header in The New York Times.

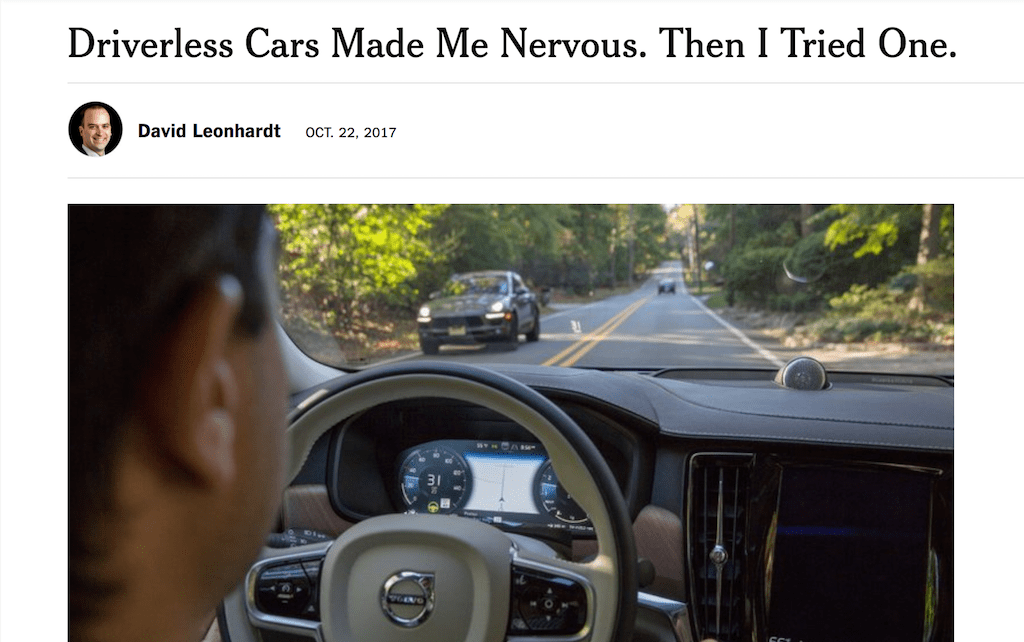

Hoo boy. The photo itself, of a driver’s hands hovering just off the wheel of the stylish Volvo S90 sedan, already suggested what was missing, namely the “driverless car” that has fueled so many media fantasies. That part was easy enough to overlook, especially since (full disclosure) I spent several years as the Times’ chief auto critic. I know too well the pressures and temptations of click-baiting headlines in an age of vanishing ad revenues and laid-off journalists. What I couldn’t overlook was the story, which – once again – promoted the fiction that “driverless” cars are already here or just around the corner; while mashing technical terms into a stew that, sure enough, upset and alarmed the educated, articulate readers of the Times. It was written by Pulitzer Prize winner David Leonhardt, who may write a mean Op-Ed but is surely not a car guy, announcing a nearly ten-year-old Toyota as his daily driver.

Remarkably, the bait-and-switch occurs before the story is even underway, with a photo caption that contradicts the “driverless car” headline, the bold emphasis mine: “A semi-driverless Volvo S90 sedan, on a recent test drive.”

The Volvo S90, of course, is not driverless, semi-driverless, or even one-tenth driverless. So my first reaction was a pang of professional jealousy: Wait, did the Times get access to some awesome Volvo prototype before The Drive? Nope. Just your garden-variety S90. Now, the Volvo is a sweet sedan, and its suite of safety technology is impressively vast. Like too many new luxury cars, it has added a parlor trick, a sporadic ability to steer itself on the freeway, which basically means wobbling between lane markers like a Swedish sailor on aquavit, until you shut that annoying shit off. But I guess we’re at the point that, if a car can roll downhill under its own power, someone will write a sensational story about “driverless coasting.”

Let’s have Mr. Leonhardt take it from here:

“On my fourth day in a semi-driverless car, I finally felt comfortable enough to let it stop itself. Before then, I’d allowed the car—a Volvo S90 sedan—to steer around gentle turns, with my hands still on the wheel, and to adjust speed in traffic. By Day 4, I was ready to make a leap into the future.”

Here I was, being whisked along into that future, when it hit me like a runamok Tesla: This Minority Report technology that Leonhardt was touting was simply adaptive cruise control, with some prosaic lane-departure technology baked in. The writer describes a successful cruise-control stop as though he was John Glenn heading into pioneering space orbit:

The cameras and computers in the Volvo recognized that other cars were slowing and smoothly began applying the brake. My car came to a stop behind the Ford ahead of me. I began laughing, even though no one else was in the car, as my anxiety turned to relief.

Wow. It’s lucky no one got hurt, aside from the Times’

increasingly endangered copy editors. Clearly no one informed Leonhardt that adaptive cruise control, or ACC, has been around for nearly two decades, beginning with Mercedes’ groundbreaking, radar-based Distronic system in 1999. The Lexus LS430’s laser-based unit barely beat Mercedes to American showrooms in 2000, with Cadillac’s XLR the first from an American manufacturer in 2003. Back then, it did seem almost magical: A car that can speed up, slow down and apply its own brakes in response to cars ahead, without so much as a peep or a peek from its human pilot. Here in model year 2018, adaptive cruising is as about as earth-shattering as radial tires, available on even mainstream economy cars, your Fords and Chevys, Hyundais and Hondas. Apparently at the Times, the automotive “future” means partying like it’s 1999.

The next oddity: The writer says that he previously sampled Tesla’s Autopilot, the closest thing yet to semi-autonomy in a production automobile. Yet after sitting through a Tesla’s impressively no-hands performance, it took him four days to summon the nerve to switch on cruise control and let the Volvo slow and stop for a car ahead? Fair enough, we’ll chalk that up to poetic license. To drum up some drama where none exists, the writer hopes to infer that these technologies can be daunting to the uninitiated, but ultimately deserving of our trust.

But then our intrepid test pilot cruises past mere fudging, and toggles up irresponsibility: “I pushed a button for driverless mode.” Once again, Leonhardt must be driving a different Volvo than the rest of us. There is no button for “driverless mode” on the Volvo S90, because that mode does not exist. Quite the opposite. From its marketing to its owner’s manuals, the ever-cautious Volvo – like every automaker, even wild-child Tesla — takes pains to underline that its safety systems demand the driver’s full attention at all times. But since the Times’ alternate Web headline reads “My Adventures With a Driverless Car,” they clearly needed a better adventure than switching on cruise control and lane monitors in a Volvo, the same sedan your Auntie drives to mahjong dates in Scarsdale. Leonhardt, already seeing his S90 demoted from “driverless” to “semi-driverless,” seems painfully aware of the need to avoid being caught out further. He avoids nearly any mention of what the Volvo can’t do, which is most anything a typical reader might consider “driverless” driving. The S90 can’t even change lanes on a highway when cued by the driver’s turn signal, which is something that Teslas, Mercedes and now Cadillacs can do.

Another doozy from the piece, which unfortunately follows the true statement that this technology is improving rapidly: “Within a few years, many cars will have sophisticated crash-avoidance systems.”

Come again? Here is his best chance to laud some of Volvo’s most winning technology, and he blows it: The S90 that Leonhardt claims to be testing already comes standard with a sophisticated crash-avoidance system, including automated braking for cars and pedestrians. Dude, that’s part of the reason your Volvo stopped before it hit that Ford! The same goes for literally dozens of mainstream models that cost far less than the Volvo, including every Subaru with the EyeSight system; and luxury cars so sophisticated that they can identify in real time the species of large hoofed animal — deer, moose, camel, horse – that they’re about to smack, so as to avoid endangering humans over, say, a darting squirrel or stray kitty cat. (PETA may not approve, but it’s likely the correct, interspecies take on the old Trolley Problem).

I eagerly await the Times’ next, spine-tingling glimpse of the autonomous future. Entitled “I Was Kidnapped by a Mind-Controlling Car from Mars,” it will reveal technology that experts are calling a “navigation system,” or “GPS.” This device will use invisible signals from outer space to fix a car’s position on the planet, track its occupants and guide the car toward its final destination, with no help from that emotionally unstable human who can’t fold a map anyway. Crazy, right? Here’s a sneak peek:

Suddenly, I realized that my car not only knew where I was headed, but was determined to take me there, without even letting me stop to relieve myself. This HAL 2000 — or maybe that’s HAL 2035 – then ordered me to “turn left on Lilliput Lane,” in a voice that I found spookily inhuman, and bossy at that. The automaton never once asked for my advice, and was clearly unaware of the trauma that would result, since I attended elementary school on Lilliput Lane and was often bullied on that very street. Clearly, these new “Driverless Directions” are as wizardly as Gandalf on an Interstate quest. Yet who, one wonders, will rule us all? What if this system asks me to drive off a bridge? Would every other driver do it, too? What if Russian hackers, directed by Putin himself, force me to turn hard right, straight to the nearest voting booth?

It’s easy to poke fun at the Gray Lady, but honestly, they’re about the 1000th publication to overplay its hand on autonomous cars. There is some good, if obvious, stuff in the piece. Leonhardt underlines that 37,000 American died in vehicle crashes last year, including most of a family in his own community; and the fact that automation has played a major role in nearly eliminating fatal crashes in commercial airliners, with the last one coming in 2009.

“Technology creates an opportunity to save lives,” he writes. “Computers don’t get drowsy, drunk or distracted by text messages, and they don’t have blind spots.”

And this, regarding the lack of perspective when it comes to the potential benefits of (actual) autonomous cars:

“I expect that we will agonize about using them, out of both legitimate caution and irrational fear. Any driverless crashes will be sensationalized, as has already happened, while we ignore tens of thousands of deaths from human crashes.”

The story cites university research that shows how people illogically resist ceding control to computers. Human subjects consistently gloss over and rationalize their own mistakes, however numerous, yet obsess over the tiniest computer error, to the point that they’re reluctant to use the machine. But Leonhardt undermines his own argument, finding fault with the Volvo system for which he himself creates unreasonable expectations:

“The technology for semi-driverless cars still isn’t good enough or cheap enough. The $50,000 Volvo I was driving — like a Tesla I’ve tried — got confused by unpainted lane lines, for instance, and I had to take over.”

Ah, finally. Welcome to the real world of “self-driving cars,” Leonhardt. The technical term for what you experienced is Level 2 autonomy, and it’s as good as it gets for now. That leaves several years and several poorly defined levels before we can sit back, down mezcal shots at key mile markers, and leave the driving to the robots. The Volvo, in fact, did not “get confused.” It worked as it was designed to, requiring you to retake control instantly when the computers lacked enough reliable data to be certain of its surroundings and make further decisions without human input. And here’s the part I can’t get over: I’m certain that anyone you spoke with at Volvo, from marketing exec to safety engineer, emphasized exactly those limitations, so that you (or the headline-writing editors) wouldn’t go calling it a “driverless car.” And yet that’s exactly what you did. Which, judging by the comments section, left many readers misled, confused, anxious or angry. The Times’ piece ultimately drives home one of the obstacles to driverless anything: Media, consumers and policymakers who know so little about modern automobiles, and how they actually work, that fear, foreboding and uninformed speculation becomes a legitimate response.

As The Drive has shouted from our Brooklyn rooftop, you can’t have it both ways. You can’t extol the world-changing potential of autonomous cars, and then wring your (partially idled) hands when they finally wrap around the wheel, and the truth. Here’s what reporters and pundits need to be telling people: There are no “driverless cars” in showrooms, or “self-driving cars,” or whatever weasel words can snare eyeballs and advertising. Someday, there will be. Some automakers have promised too much, too soon. That bugs us, too, but it’s part of their job. It’s largely the media, led by the usual Silicon Valley sycophants, that keeps hyping cars that don’t exist, and misrepresenting the features that do. That’s not their job. Considering the human error and all-thumbs coverage of this ongoing revolution in automobiles, some “self-writing stories” would be an improvement.