The aftermath of World War II saw the popularization of both car and air travel, and it was inevitable that someone would think to combine the two. People didn’t just want to fly to their destinations; they wanted to take their cars too. That led to the creation of a new type of plane, the ATL-98 Carvair, which was thought at the time to herald a new niche of air travel.

The Carvair’s story actually started 16 years before its first flight, all the way back in 1945 according to Mentour Pilot. The Bristol Aeroplane Company had just launched the Type 170 Freighter, a small, rugged cargo aircraft meant to carry loads like a three-ton military truck. It arrived too late to contribute to the war, but just in time to meet growing postwar demand for short-haul flights between continental Europe and the British isles. One of its operators eventually realized the oddly shaped aircraft—which was meant to carry a truck—could fit cars instead, and the air ferry was born.

Though popular in subsequent years, the Bristol air ferries weren’t perfect. Chiefly, they were so small that if one of the ticketed cars canceled, the flight could lose money. To low-cost airline pioneer Sir Freddie Laker, the solution was obvious: Make it carry more cars. Developing an all-new successor to the Bristol would’ve been a daunting task for Laker’s company Aviation Traders Limited, but Laker was about to have a stroke of luck.

By the late 1950s, jet aircraft were taking to the sky en masse, replacing hundreds of perfectly good, but unwanted piston-engined aircraft. Douglas DC-4s and their C-54 military counterparts were dirt-cheap, but still widely supported and easy to work on. That made them perfect for adaptation into the ATL-98 Carvair. (Car-ntrary to their punny names, Convair doesn’t seem to have been involved at all. I haven’t seen a picture of one transporting a Chevy Corvair, either.)

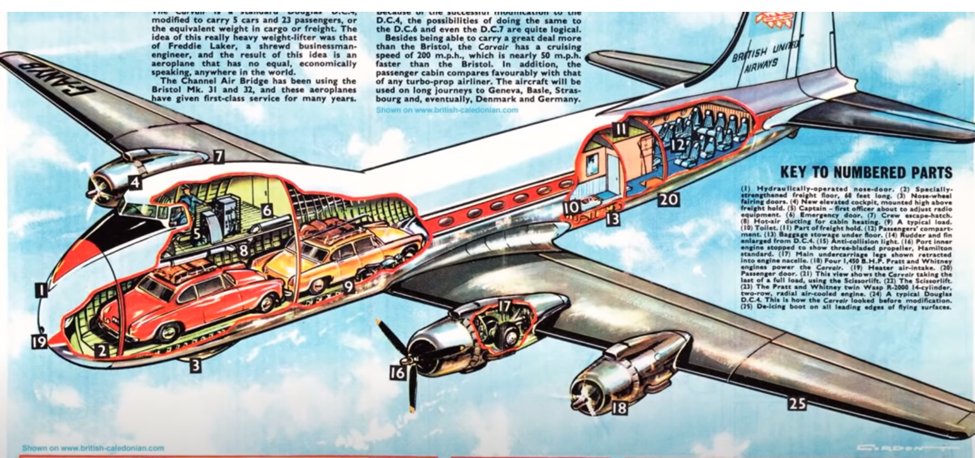

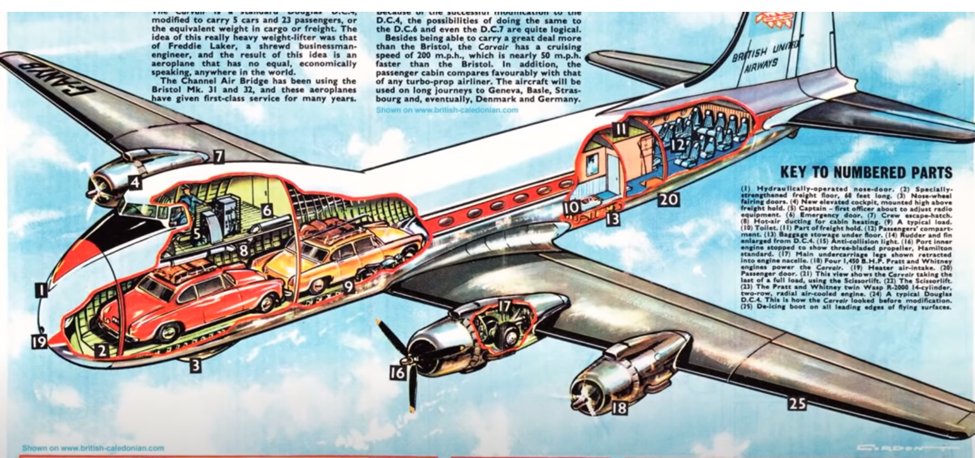

The Carvair had its front end modified to elevate its flight deck, while its nose was fitted with a swing-out door for loading cars. Its cargo bay was better suited for large contemporary cars than the Bristol it replaced, while the rear of the fuselage featured an enlarged vertical stabilizer and rudder for stability. The result was a plane that could accommodate varying numbers of cars and passengers based on configuration, though the most common setup apparently held five cars and 22 passengers. Conversion was also reportedly more expensive than the donor plane, though the entire machine supposedly cost the modern equivalent of $3.6 million.

A prototype first flew on June 21, 1961, beginning an unusual, broad, and decades-long career for the quaint Carvair. The 21 Carvairs built were used in air ferry service by numerous airlines on multiple continents, but also by the International Red Cross and the oil industry. One even appeared in James Bond film “Goldfinger,” where it was used to transport Auric Goldfinger’s gold-bodied Rolls-Royce Phantom III.

Prior to its first flight, the Carvair was hoped to be a stepping stone to bigger, better air ferries that could be based on the later DC-6 and DC-7. It was reportedly believed these would arrive on a similar time frame to the Carvair, replacing it about 15 years into its service life. But while the Carvair indeed flew with commercial airlines into the 1970s, it was never followed up.

Plane manufacturers were supposedly wary of investing in new planes for an ultra-niche market, which was under challenge by faster seaborne ferries. More accessible car rental probably hurt too, not to mention fast hovercraft ferries that—at least for a time—seemed to combine the best of both worlds. On a longer timeline, construction of the Channel Tunnel and heightened airport security probably kept the air ferry in the dirt.

That doesn’t meant the Carvair is a long-dead, forgotten piece of history though. Carvairs actually operated into the new millennium, as they were just easy to keep running. While eight have been destroyed in crashes over the years, and none have flown since 2007, at least two are on display in different parts of the world. For even that many of such an odd, relatively unknown clash between the automotive and aviation worlds to survive is practically a miracle. After all, plenty of more widely beloved, more iconic vehicles haven’t been as lucky.

Got a tip or question for the author? You can reach them here: james@thedrive.com