We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn more ›

We’ve said it again and again: every garage needs a 3D printer. If our word isn’t gold for you, just take a look back at The Great Ford Maverick 3D Print-Off where Peter Holderith and I designed some sweet accessories for Ford’s most affordable pickup. In that case, Ford was helpful by publishing the blueprints for the truck’s Ford Integrated Tether System (FITS), but other automakers aren’t so generous.

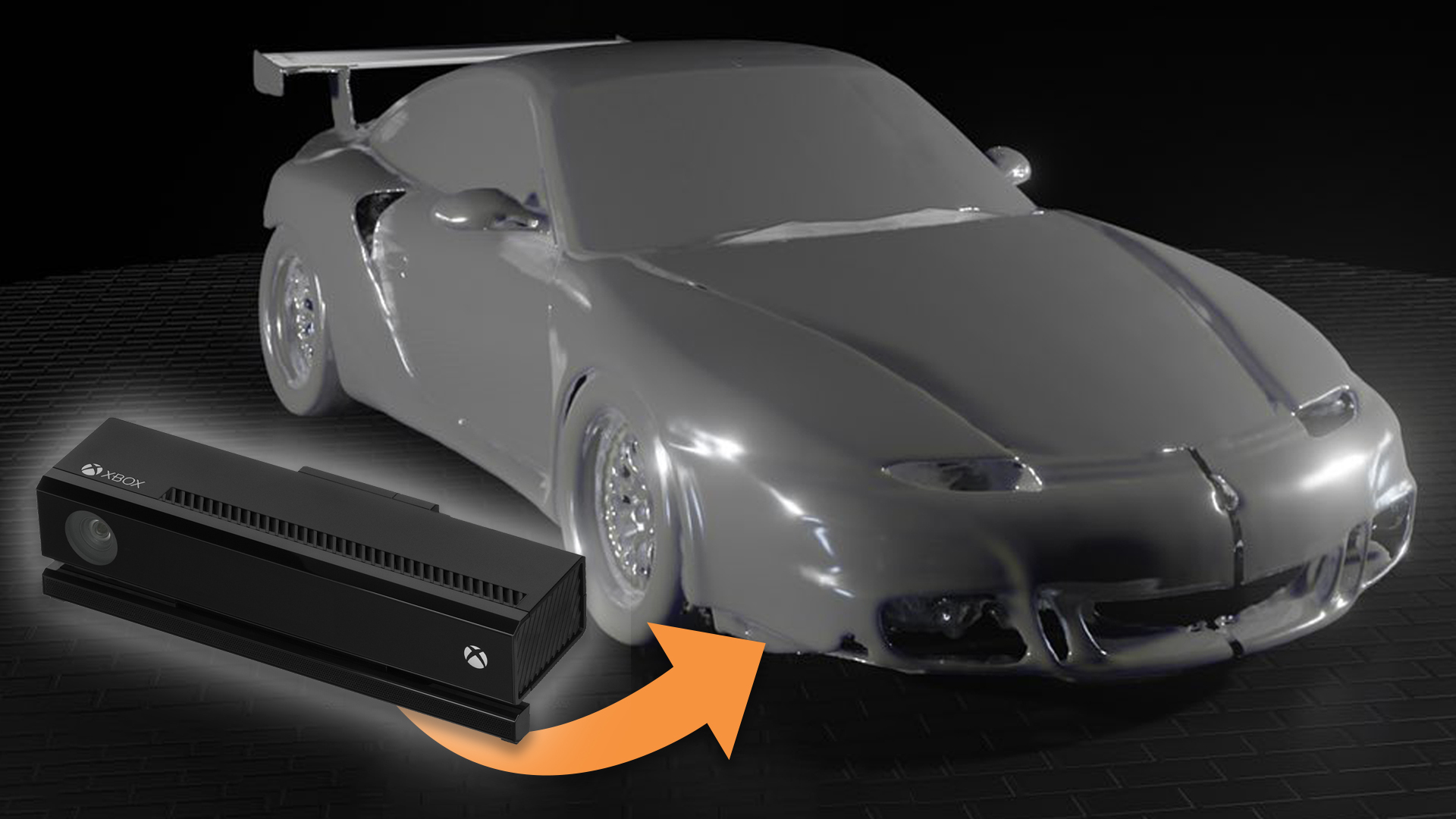

To fix this, DIYers have resorted to reverse-engineering their cars. Some break out the calipers and contour gauges while others who are a bit more tech-savvy have resorted to 3D scanning. Surprisingly, it doesn’t take much money or the newest tech to get started in the scanning world. In fact, you can simply pick up a discontinued Xbox Kinect unit to get started.

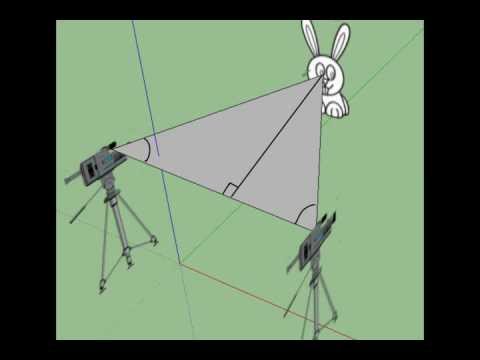

Before we get into what people are doing with these cheap devices, it’s important to understand how they work and why they provide so much more of a benefit over a flat photo. The reason that a regular camera can’t be used is that standard imaging sensors are essentially monoculars. They have no native way to measure depth.

To solve this problem, many robotaxi start-ups use lidar technology. Lidar sends out beams of light to form a point cloud; that’s a set of points along cartesian coordinates in space which represent a 3D object. In Tesla’s case, multiple cameras can be used to form a stereoscopic view of the world and artificially measure distance, though it’s often debated how accurate software can create these measurements compared to purpose-built sensors.

The magic in Microsoft’s Kinect sensor is almost like a hybrid of both solutions. While not as robust as a lidar sensor, the Kinect uses beams of light (like the lidar) as a method to gauge the distance of an object. It also uses a two-camera setup, where one camera uses a standard vision sensor, and the other is used to view the grid of infrared beams that are projected by sensors mounted inside the Kinect. By mapping the location of dots projected by the infrared grid, the sensor is able to overlay both feeds to form a single image with depth information baked in.

Now that we understand roughly how the Kinect works, let’s check out just how enthusiasts are using it to build their dream cars.

DIYers and builders alike are primarily using these Kinect-produced scans to either reverse-engineer parts of the cars or make it easier to model against complex shapes and contours. For example, one Miata owner used it to make new headlight buckets, another used it to design a spoiler for their Audi, brake ducting, switches, center consoles (with gauge pods cutaways), replacement door handles, and even entire intake manifolds.

Plenty of other examples can be found in some of my favorite car-related 3D printing Facebook groups, like “3D Printing Auto and Moto” and “Miata 3D Printing Association.” But there’s one particular project I’d like to call ours which I’ve showcased before; Crucible Coachworks’ Porsche 911 slantnose build.

Ryan Krause, the builder of this 996-turned-flachbau, has been posting updates on social media for some time. Throughout the years, he’s outlined just how classic metal shaping techniques can be used alongside modern 3D printing—and the Porsche’s retro look is a perfect example of how those two can be blended together.

Krause started his 3D printing adventure with old-school measuring tools. Modeling eventually became complex when he needed to design headlight buckets, grilles, and other custom parts. This was before the build amassed hundreds of thousands of followers on TikTok and Instagram, so Krause did what any other budget-conscious 3D printer would do; he bought a Kinect.

Here’s the basic workflow of how capturing a model and designing a part works. First, Krause used Skanect to capture a 3D model with the Kinect sensor. After it was captured, he imported the model into Blender to clean up any anomalies and then brought the simplified model into Fusion 360 where he scaled it to size. Then, it was all about designing the prototype of his next part.

It’s not all roses and sunshine with the Kinect, though. With a big enough model, scans become sluggish or lose tracking. He would eventually upgrade to a purpose-built, still budget-friendly option, the Creality CR-Scan 01. It allows for more accurate scans. He used these scans to produce prototype turn signal lenses, ducting, and vents, as well as headlight buckets for his various Porsche projects.

If you’ve been looking for a new hobby to complement your car addiction, I’m once again going to recommend 3D printing. Once you learn how to make your own parts, you become pretty much unstoppable—or at least limited by your ability and access to materials. So what are you waiting for? Get out there and start printing.

Got a tip or question for the author? Contact them directly: rob@thedrive.com