Thirteen years ago, Cash For Clunkers offered a unique premise. Help save a floundering domestic auto industry, inject badly needed capital into an economy ravaged by a massive recession, and replace aging guzzlers on American roads with more efficient cars. The federal scrappage scheme targeted inefficient vehicles for destruction following some basic criteria: cars younger than 25 years, with a combined miles-per-gallon figure of 18 or less, and in drivable condition. Beyond that, the cash owners received had to be put towards a new car that would be registered and insured for one continuous year after purchase.

In the end, a total of 677,081 used cars were pulled off the road. For years, rumors circulated of people trading in 1980s and 1990s exotics, luxury cars, and all manner of other future classics, but the full picture of what was lost remained cloudy. Until now—we’ve dug up a little-known, long-lost complete report on every car CFC destroyed. With talk of a new buyback program to push people from internal combustion to electric vehicles echoing through Washington D.C., it’s the perfect time to revisit what happened the last time we cashed in our clunkers.

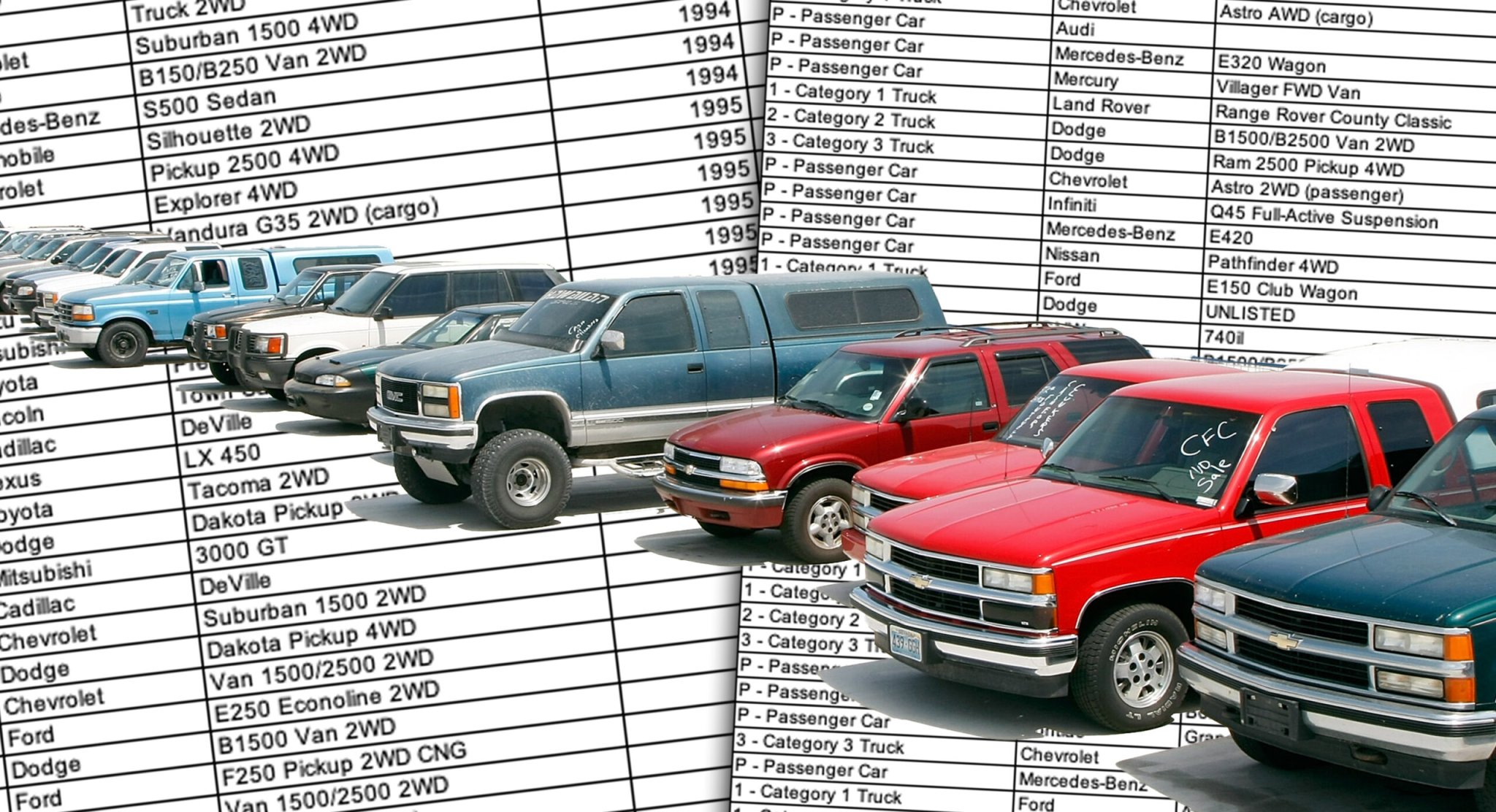

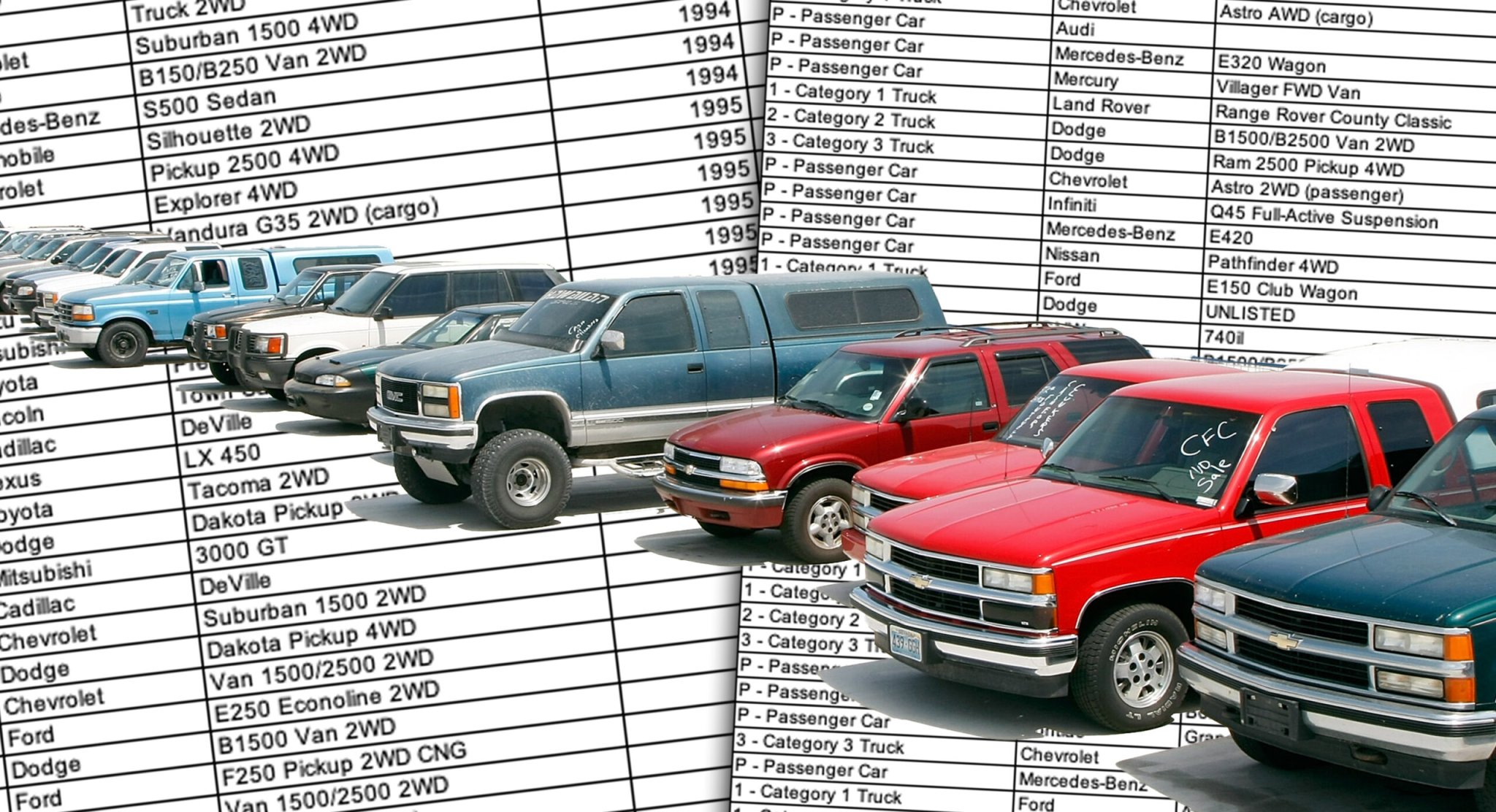

We found the report on a Wayback Machine archive of CARS.gov, the website of the Car Allowance Rebate System, aka Cash For Clunkers. The site has now been offline for more than five years, but the complete record of every one of the nearly 700,000 vehicles destroyed survives. While there was plenty of wailing and gnashing of teeth about CFC claiming a few exotics, that coverage wasn’t based on an audited list to eliminate incorrect entries, duplicates, and other errors.

Now we have finalized data that gives us insight into what was destroyed under CFC—and yes, that includes a number of cars that’ll really make you wince. We’ve got a few stories coming up that will go through everything with a fine-toothed comb, including one on the classics, rarities, and performance cars that met their fates during those heady days of summer 2009.

But first, here is the full list of scrapped cars and trucks. We’ve embedded the PDF below, sorted in alphabetical order by manufacturer. We’ve also set up a public Google Sheet linked here in case there’s an issue with the PDF. Take it all in:

Cash-For-Clunkers-Trade-In-ListI wanted to start by looking at what CFC destroyed the most. But because of how the report is formatted, that’s far from easy. Vehicles are split up by year, make, model, and drivetrain configuration, splitting single models into several entries. Even so, I was able to skim the cream off the top by processing only the top 150. That still gave me a pretty good idea of what cars CFC claimed the most of. And here they are:

- 1995-2003 Ford Explorer/Mercury Mountaineer: 46,676

- 1996-2000 Chrysler/Dodge/Plymouth minivans: 23,998

- 1993-1998 Jeep Grand Cherokee: 20,844

- 1992-1997 Ford F-150: 20,222

- 1984-2001 Jeep Cherokee: 18,329

- 1988-2002 GM C/K pickup: 17,202

- 1995-2005 Chevrolet Blazer: 15,668

- 1999-2003 Ford Windstar: 12,157

- 1991-1994 Ford Explorer: 11,612

- 1994-2001 Dodge Ram 1500: 8,103

While the list is a neat cross-section of the most popular cars in the U.S. at the time, popularity alone isn’t why these vehicles were the most crushed. They were destroyed because CFC was meant (at least ostensibly) to boost the poor fuel efficiency of U.S. drivers’ cars. Not a single vehicle above beat 18 mpg with an automatic transmission, and in aggregate they average barely 16 mpg.

That happens to be pretty much the average for all CFC turn-ins, which the Department of Transportation calculated to be 15.8 mpg. Because CFC worked on a rebate system, where dealers got cash for accepting discount vouchers, the federal government could track the margin of gas mileage improvement for every sale. In doing so, it found the average mpg of replacement vehicles under the CFC program was 24.9 mpg—an improvement of 58%.

But while 700,000 vehicles gaining over 9 mpg sounds like a lot, the U.S. Energy Information Administration noted no improvement to the nation’s motor vehicle fuel economy as a result of CFC. If anything, it recorded a marginal decline from 2009 to 2010. CFC’s effect on U.S. fleet fuel consumption was further diluted by subsequent years of record car sales: since 2010, over 185 million new cars have been sold in the U.S. according to Axelwise.

The program’s effect on our gas consumption was ultimately negligible, and that goes without acknowledging CFC’s other downsides. It cost the U.S. government $3 billion, some of which indirectly supplemented the bailouts issued to U.S. automakers, though much of it went abroad. Apocryphally, CFC was also blamed for a rise in used car prices. But that might be explainable as the outcome of more demand for cheap used cars during the recession.

“Recession” is on economists’ tongues again, so are proposed CFC revivals, sometimes aimed at EV adoption—the latter has been proposed in D.C. according to speculative reports. If the U.S. indeed enters another recession, and a CFC-style program returns, then its proponents must take into account what happened the first time we tried cashing in clunkers, not to mention the differences in market conditions between 2009 and 2022. Then, demand was the problem; today it’s supply, and an EV CFC could quickly turn into a windfall for car dealers and few others.

We can speculate on whether CFC achieved what it set out to do, and we will. But not up for debate is what’s gone, and here’s the final list.

Got a tip or question for the author? You can reach them here: james@thedrive.com