Most automakers avoid the term “appliance” like the plague, as it’s come to define the kind of characterless car that exists to get people from A to B, nothing more. But that hasn’t always been the case—in fact, there was a time when just about every major American car company was all-in on the appliance business.

Back in the mid-20th century, your average home was stocked with stoves, washing machines, air conditioners, and especially refrigerators built by various divisions of Ford, General Motors, AMC, and more. It might sound odd today to think of buying an International Harvester fridge or a Chrysler home A/C unit, but it once was a common sight thanks to a unique mix of socioeconomic factors that all converged in the postwar era.

Of course, we’re no longer cooking dinner on stoves designed by GM and fetching ice cream from our Ford-made freezers. By the late 1970s, every single domestic automaker had sold off their appliance divisions—many to the same corporation—as their efforts began to spoil. So why did so many automakers expand into entirely new industries in an effort to conquer the modern American home? And what caused them all to leave it so rapidly?

Cold Start

To get the full picture, we have to rewind back to 1918, when GM founder William Durant personally invested in the faltering Guardian Frigerator Company, which had produced the world’s first refrigerator cabinet a few years earlier but failed to make any money off it. Durant renamed the business Frigidaire, then used his stake to engineer a sale of it to General Motors shortly thereafter, and Frigidaire became a full subsidiary in 1926. Frigidaire’s association with GM allowed it to borrow similar mass-production techniques that were revolutionizing the auto industry, with sales growing and prices falling as a result. The company emerged as a major innovator, pioneering new features and layouts, and the name “Frigidaire” soon became a generic term to describe all refrigerators, regardless of brand. (Think Kleenex or Band-Aid.)

The Chrysler Corporation’s foray into refrigeration started at a much larger scale, during Walter P. Chrysler’s construction of the new Chrysler Building in New York City in the late 1920s. Unsatisfied with existing commercial air-conditioning equipment, he tasked company engineers with finding a better solution to cool what was briefly the world’s tallest skyscraper. Eventually, their efforts led to the Airtemp Corporation, incorporated in 1934 and then reabsorbed into Chrysler in 1938. Airtemp branched out to railcar air conditioners and other HVAC equipment, later on moving into the residential air conditioning business as demand grew in the postwar period.

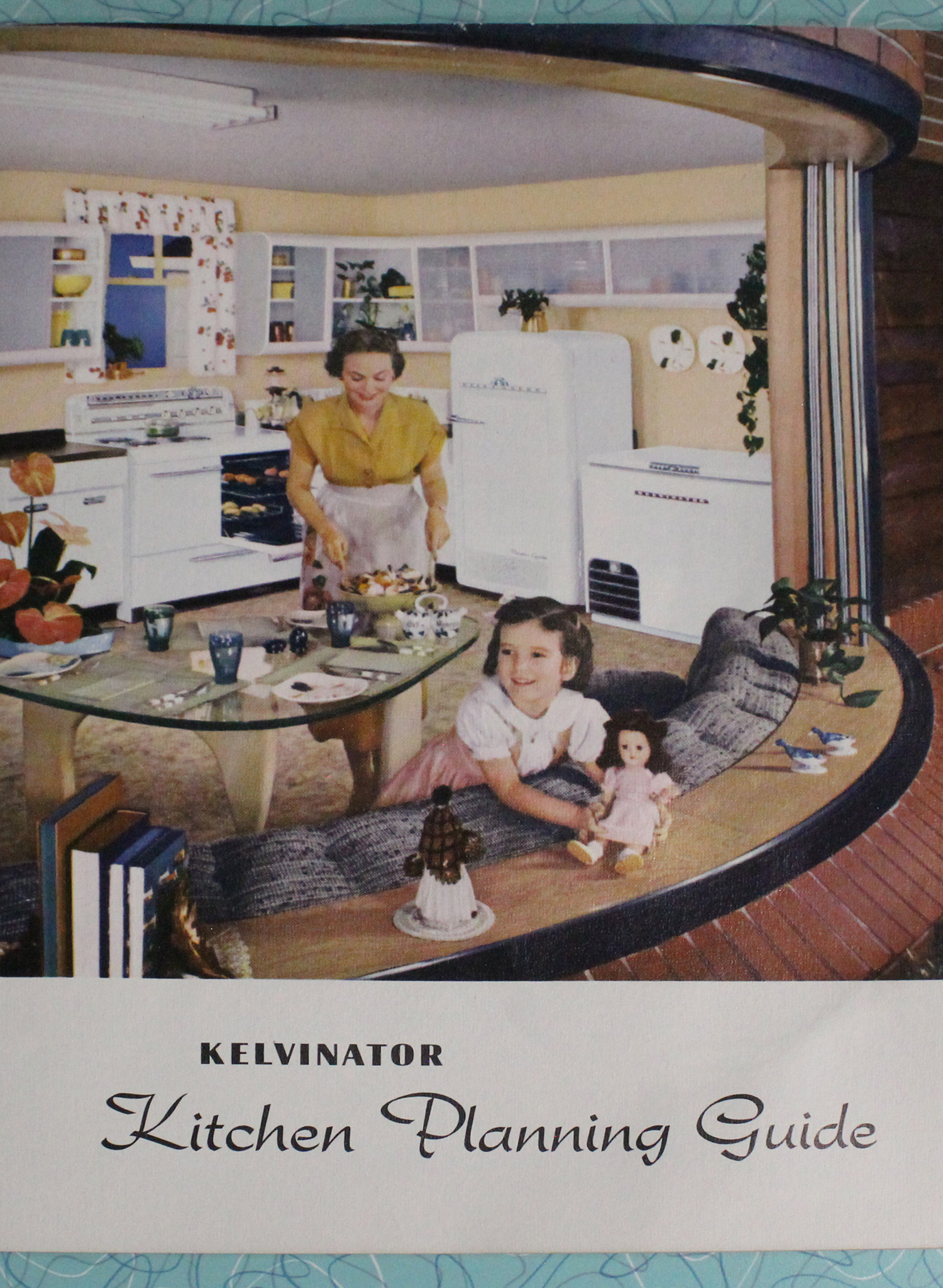

Then there was Nash Motors, which eventually became AMC and a real force in the home kitchen through its Kelvinator line of appliances. In the late 1930s, founder Charles Nash was looking to retire and wanted a man named George W. Mason to take over for him. However, Mason refused to leave his role as president of the Kelvinator Corporation. Established in 1916 and named in honor of British scientist Lord Kelvin, Kelvinator started out by producing separate electric cooling units to retrofit into existing iceboxes, before producing the industry’s first entirely self-contained refrigerator in 1926. Unable to pry George Mason away, Charles Nash agreed to merge their two companies in 1936 if Mason would take charge of both. Thus, Nash-Kelvinator was created, and the prewar auto-appliance alliance boom was on.

Innovation and Expansion

Meanwhile, serial entrepreneur Powell Crosley took an opposite approach, going from appliances to cars. After selling car accessories, he started manufacturing radios in 1919, which led to other home appliances, which led to his company introducing the first refrigerator with shelves built into the door (appropriately called the Crosley Shelvador) in 1933. The success of his appliance business would later help finance a separate automobile manufacturing business he started in 1939.

As electricity service spread across the country in the 1920s and ‘30s, the popularity of household appliances exploded. Even through the Great Depression, sales continued to climb as New Deal programs brought electricity to rural areas for the first time. Manufacturers expanded their product lines beyond refrigerators into freezers, stoves, ovens, air conditioners and more. Plus, automakers began to realize the untapped potential for their divisions to collaborate.

By the 1930s, aftermarket companies had begun installing custom air conditioners in cars, but the Packard Motor Car Company became the first automaker to include it from the factory. For 1940, buyers had the option of “mechanical refrigeration,” which cost around $275 and added a system built by Bishop & Babcock Manufacturing that blew cooled air around the car’s interior. Cadillac followed with a system in 1941 and Chrysler in 1942. These early A/C units were expensive and bulky, requiring extra equipment to be installed in the trunk or behind the rear seat, taking up space.

Progress was soon interrupted by America’s entry into World War II in 1942 and the domestic manufacturing upheaval it caused. As with their vehicle divisions, automakers turned their appliance factories over to wartime production. Soon they were cranking out guns, ammo, aircraft components, and more. Their technological expertise even served the war effort directly; Kelvinator’s British operations helped test airplane equipment at low temperatures, Crosley built radio proximity bomb fuses, and Chrysler’s Airtemp even assisted in the Manhattan Project.

A Red Hot Market

After the war, consumers were hungry for, well, everything. Nearly five years without new cars or appliances sent demand through the roof. Sixteen million returning veterans were ready to start new lives back home. The recently passed G.I. Bill provided financial assistance with college tuition, home loans, and more (though discrimination prevented all Americans from benefiting from these programs equally). The middle class began to balloon in size, with new houses and entire suburban communities springing up all over the country.

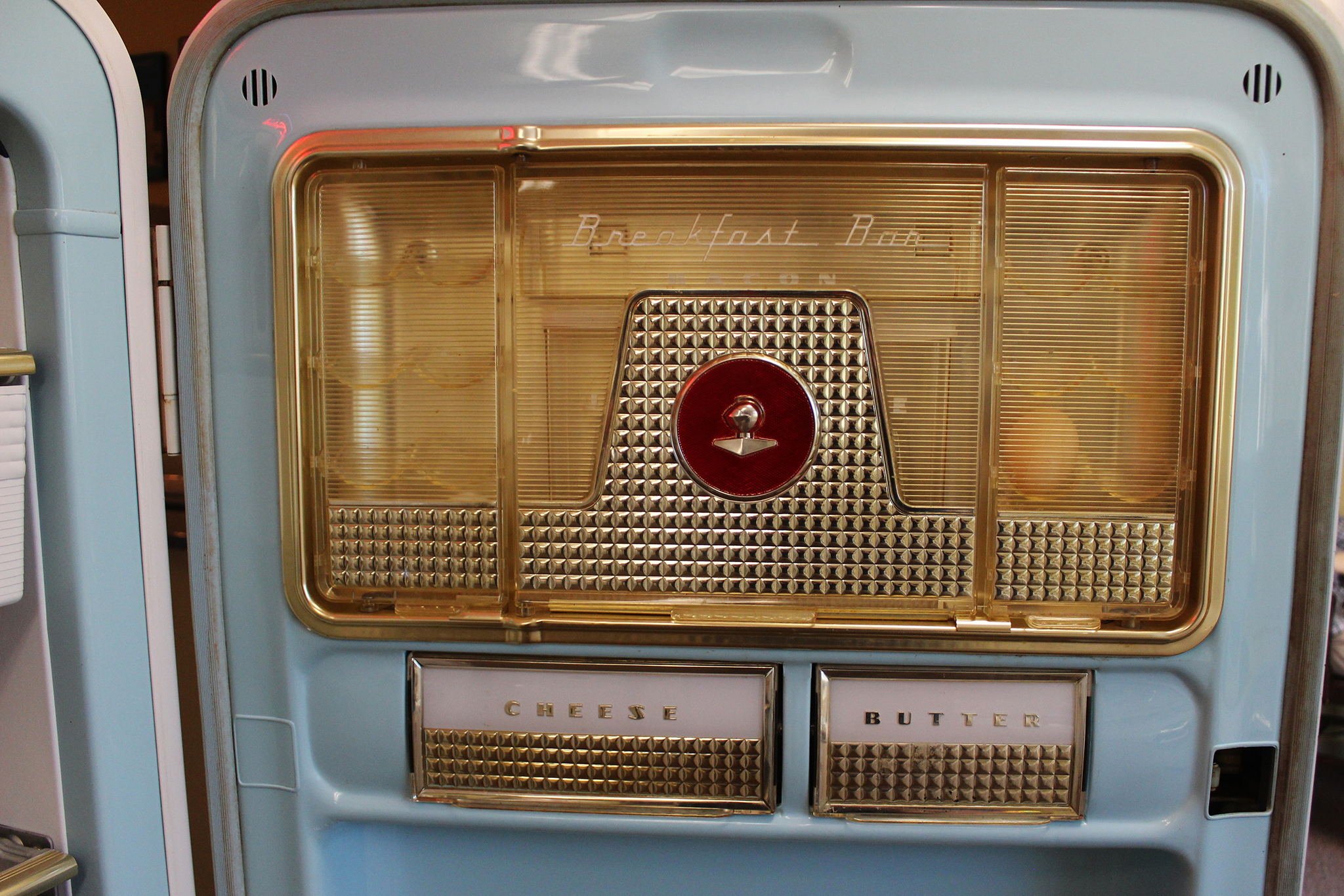

Of course, people were looking to fill their nice new houses with new appliances and new cars in their driveways, and corporations were eager for their slice of the market. Still wholly owned by GM, Frigidaire innovated with new fridge features like auto-defrost and new colorful designs. Kelvinator launched a line of steel cabinets to go with their existing equipment, making it possible to build an entire kitchen with Kelvinator-branded products. Appliances became fancier, with catchy names like “Foodarama” and gorgeous designs that looked more like art-deco movie theaters than a place to store butter and eggs.

Ever the outlier, Crosley sold his entire appliance company to AVCO in 1945 to focus solely on building cars (and owning the Cincinnati Reds). The automotive venture sadly fizzled out by 1952, but his name continued to appear on radios, TVs, and refrigerators until 1956.

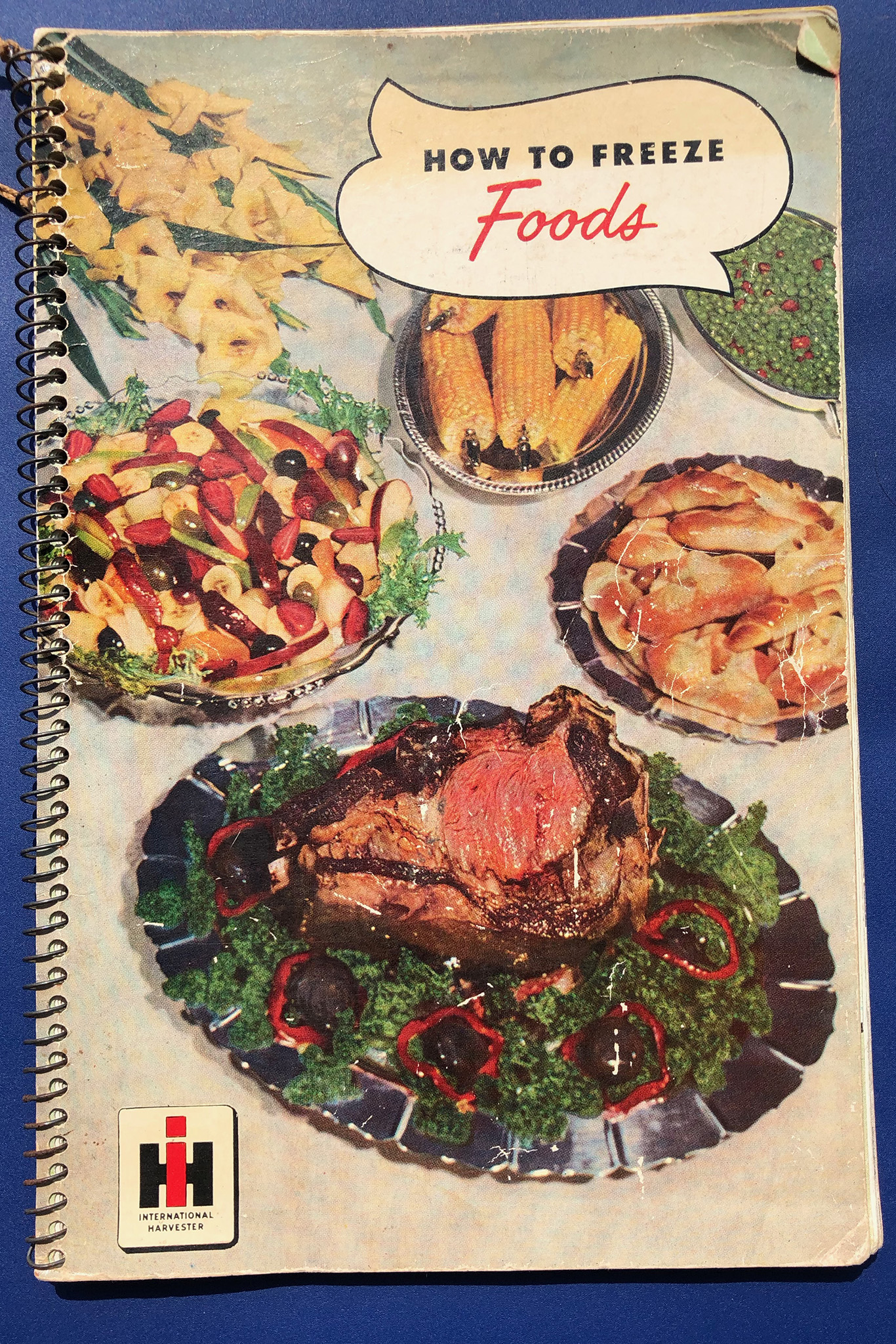

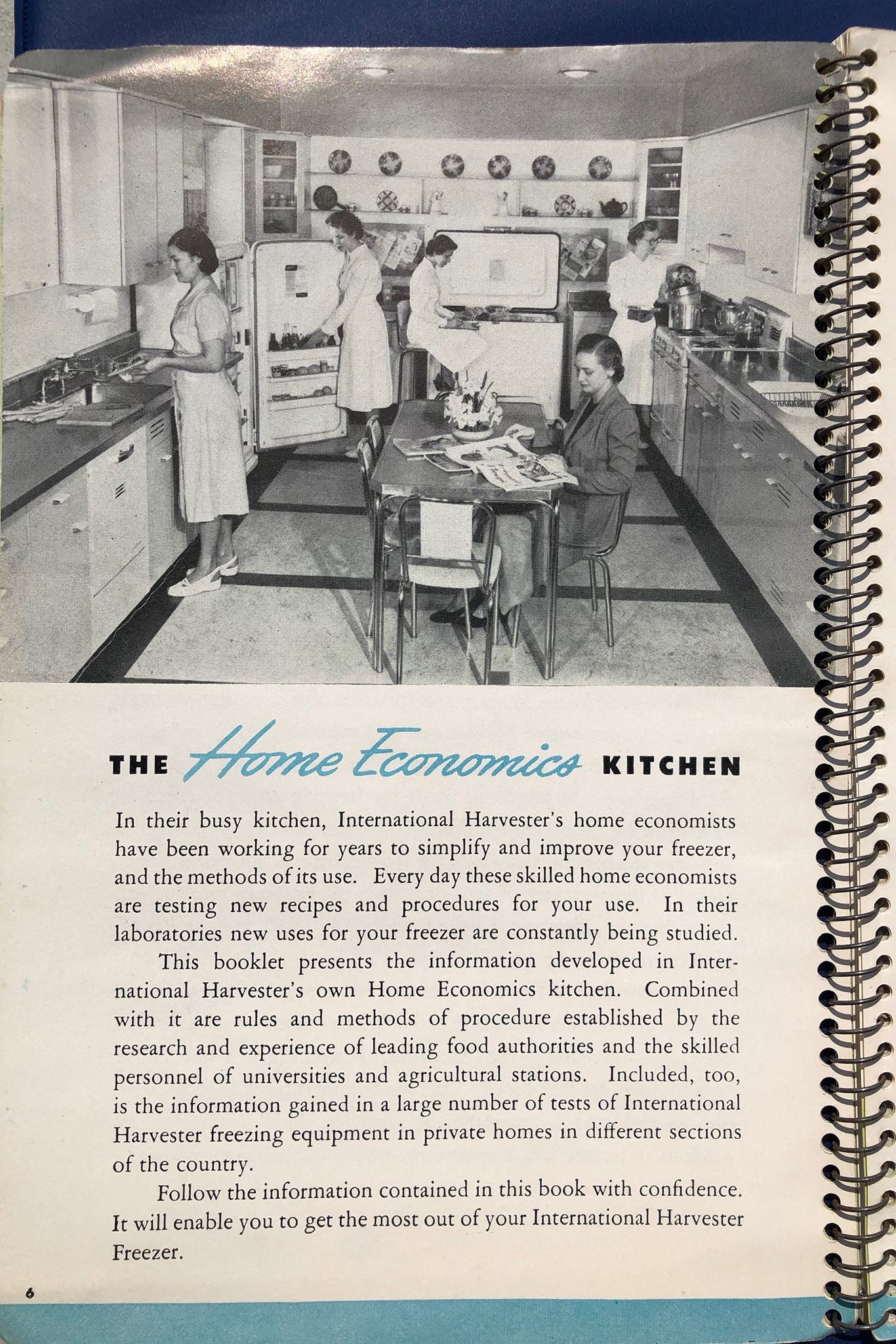

While Crosley was getting out, International Harvester—best known for building farm equipment and large trucks—couldn’t resist the temptation to jump in and launched its own refrigerator and freezer lines in 1947. It seemed like an odd move, but IH already built large-scale cooling and pumping equipment for dairy farms, so home appliances weren’t a big stretch. But instead of suburban markets, IH specifically targeted rural areas, claiming their products were “femineered” with the needs of farm women in mind.

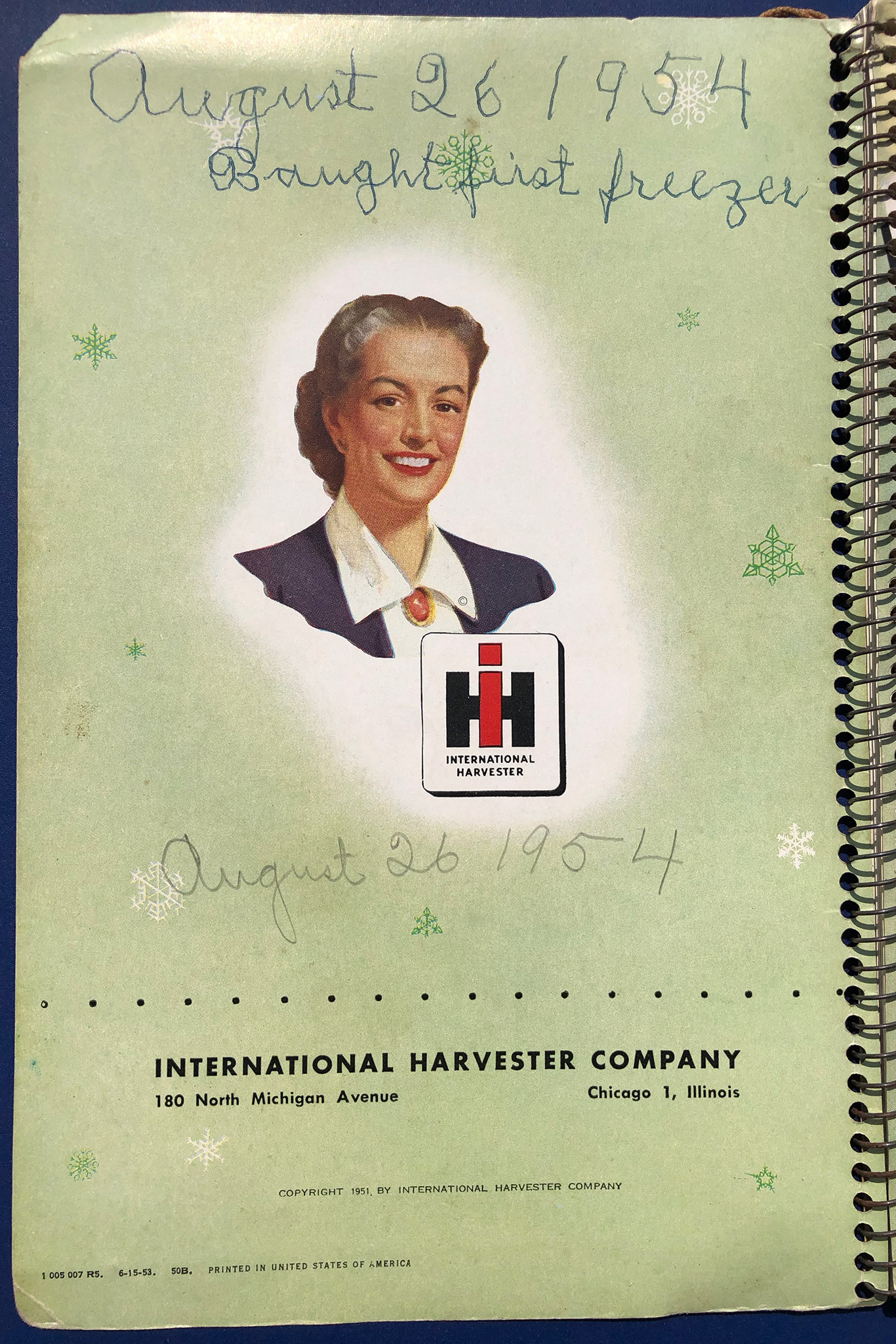

Fictional spokeswoman Irma Harding appeared in colorful ads, encouraging home cooks to give up the laborious process of hot water canning and switch to freezing their vegetables instead. IH hired dozens of saleswomen to drive around the country and promote the ease and benefits of freezing produce to rural audiences. It all sounds a little hokey, but to families not used to the convenience of electric refrigeration, there was a genuine learning curve. (Note the photo of the pamphlet with the handwritten note saying the family bought their first freezer in 1954!)

IH was not alone in this endeavor to educate the public. Multiple manufacturers published cookbooks promoting all the delicious things you could make in your upgraded kitchen. Promotional films extolled the time-saving benefits of new appliances, painting a white-washed image of 1950s domestic bliss. Idealized (and often sexist) though the advertising may have been, appliances did reduce the time and toil of household chores. This genuinely improved lives, especially for women.

Sadly, International’s appliance division lasted less than a decade. As with cars, the postwar boom eventually cooled and the market became increasingly competitive. IH bowed out of the appliance business in 1955, selling the entire division to Whirlpool. It was a sign of things to come.

Eye on the Weather

Air conditioning’s slow proliferation across new cars continued after the war, although the bulk and expense of systems still limited their appeal. Frigidaire began manufacturing units for GM cars in 1953, and Chrysler introduced Airtemp A/C units on 1950s Imperials (although some were built by outside suppliers). Automakers were definitely still figuring out the kinks; cars back then typically had separate systems for heating and cooling, with the A/C vents looking tacked on in the cabin and its plumbing consuming valuable trunk space.

Nash, relying on the expertise of its Kelvinator appliance division, introduced a major innovation in 1954: the first automotive A/C system fully contained under the hood of a car. Pontiac soon followed, although its system was designed by GM’s Harrison Radiator division, not Frigidaire. Nash had long been a leader in automotive heating and ventilation with their ground-breaking Weather-Eye system, and soon they became a leader in vehicle air conditioning as well.

This carried on after the company’s merger with the Hudson Motor Car Company in 1954, which created American Motors Corporation. It wasn’t long before other car companies followed suit and introduced their own under-hood air conditioners. What was once a rare, exotic feature was becoming more common.

Buying and Selling

The idea of an auto-appliance alliance must have seemed irresistible at that time, as Ford finally jumped into the pool with its purchase of Philco in 1961. While better known for radios, televisions, and other consumer electronics, Philco produced refrigerators and freezers as well, including a unique model with a double-hinged door that opened from either side (Which, unfortunately, often resulted in the door falling off completely as the hinges wore out.) Studebaker, then on a crazy diversification binge in its final years, purchased Franklin Manufacturing in 1962, which built private-label appliances that were rebadged as other brands.

By the mid-’60s, GM, Ford, and AMC all had major home appliance lines. Only Chrysler hadn’t ventured into refrigerators, but its Airtemp division was still building plenty of A/C systems for both residential and commercial use.

It’s perhaps no coincidence that the 1960s saw the creation of some of the most beautiful designs in appliance history. Advances in engineering allowed machines to become smaller, slimmer, and cleaner looking. GM designer M. Jayne van Alstyne became studio head of Frigidaire and ushered in a new era with the groundbreaking 1962 Frigidaire Flair electric range. With glass oven doors that swung up out of the way and a sliding drawer for the burners, its smooth, space-saving design became symbolic of what we now know as mid-century modern design. Kelvinator launched a new line of “Originals,” which featured a slew of decorator trim choices from classy to cartoonish to downright gaudy.

But the fun didn’t last, as those appliance divisions began to experience economic conditions that would later hit their automaker parents. Rising manufacturing costs in the U.S., combined with competition from cheaper imported products, were making businesses a lot less profitable.

Studebaker ceased car production by 1966, and it sold off the Franklin Appliance division the following year as it continued to restructure itself into irrelevancy. At the same time, AMC was sinking further and further into the red, and its new management decided to sell off Kelvinator in 1967 to raise some desperately needed cash. It wasn’t for naught, as the sale helped fund new cars like the AMC Javelin and AMX, plus the eventual purchase of Jeep from Kaiser Industries.

Still, things were moving fast; in 1968, the Cadillac Fleetwood Limousine and the AMC Ambassador became the first American cars with standard air conditioning, though many more offered it as an option. By 1969, 54 percent of all cars sold in the country had it either optioned or as a standard feature. A/C was no longer a luxurious novelty; it was almost a given.

There’s Always a Bigger Fish

Interestingly, Studebaker and AMC both sold their appliance lines to the same company in the 1960s: the mysterious-sounding White Consolidated Industries. WCI was a former sewing machine manufacturer that had rebuilt itself as an appliance company with a “slash and burn” business model. It acquired other companies on the cheap, implemented brutal cost-cutting, and watched the profits roll in. At Kelvinator alone, almost three-quarters of the administrative staff were fired in the first month after purchase. WCI would go on to buy Philco, though not directly from Ford, who first sold it to GTE-Sylvania in 1973.

Finally, after holding out the longest, GM capitulated and left the appliance industry, too. GM management spun off the automotive portion into Delco Air Conditioning in 1975 and sold the legendary Frigidaire division to WCI in 1979. Only Chrysler’s Airtemp avoided the clutches of WCI, instead ending up as part of another air conditioner manufacturer, Fedders. Meanwhile, the former Airtemp factory in Bowling Green, Kentucky was purchased by GM and rebuilt as its now-iconic Corvette plant.

The reasons why automakers abandoned the appliance business are numerous, but for GM and Ford, a large part of it was due to the economic stagnation of the 1970s. Weak sales and rising costs meant the cash flow was tight, and selling an unprofitable division to a willing buyer was a quick way to funnel capital toward automotive operations, which were also undergoing massive changes in the ‘70s. As the appliance market matured, it continued to become more and more commoditized. Products became less distinct, and consumers flocked toward whoever had the lowest prices. This, in turn, created razor-thin profit margins.

After years of gobbling up other companies, White Consolidated Industries found itself with a case of indigestion. The business of “consolidating” all those divisions, plants, and product lines scattered around the country was difficult. In the process, WCI caught the attention of a Swedish manufacturer by the name of Electrolux, and soon the king of acquisitions itself was acquired in 1986.

Defrost Cycle

For a time, the simultaneous manufacturing of automobiles and appliances did make sense. (And for conglomerate companies like Mitsubishiu, with its unique keiretsu structure, it still does.) Over the years, various divisions were able to share design and engineering staff, marketing materials, manufacturing capacity, and even showroom space. Had it not been for Kelvinator, Frigidaire, and Airtemp, the proliferation of in-car air conditioning may have taken much longer. Ultimately, however, changing economics led the two industries down separate paths, and keeping them together proved unsustainable.

Today, Electrolux still owns most of the brands mentioned in this story, but the trademark situation is a bit confusing and differs based on where you live. You can still buy a Frigidaire for your kitchen in the U.S., but the Kelvinator name is only used on commercial kitchen equipment. If you live outside North and South America, however, Electrolux will sell you a personal Kelvinator or even a Philco fridge, but they look completely identical save for the logo on the door. Some of those products are still made in the U.S., so at least they’ve got that going for them.

International Harvester icon Irma Harding reappeared for a retro-themed cookbook in 2014, which was sold through Case IH tractor dealerships. (There was also a vintage IH fridge on the TV show Friends.) Airtemp still exists, and though its post-Chrysler history is a little complicated, the brand still offers a line of air conditioners, heat pumps, furnaces, and more. The Crosley name has been resurrected twice, for appliances and retro-styled audio equipment.

The era of buying a new appliance with a Blue Oval or a GM Mark of Excellence is long gone, but for a dedicated community of vintage appliance collectors, it’s still a point of pride to have their brand loyalty extend from the garage into their kitchens. It’s a reminder of the past, when home goods were about more than just a race to build things at the lowest possible prices. Seeing the wonderful appliance collection at the Rambler Ranch car museum actually inspired me to write this article, and I’m still particularly envious of owner Terry Gale’s slew of Kelvinator items that prominently feature a “Product of American Motors” badge.

Today we think of an appliance as just that, an appliance. It’s a tool to do a job. But for many Americans in the 20th century, they were much more. Appliances were labor-savers that made family life easier. Appliances were time savers that helped make Women’s Liberation possible. Appliances were live savers that allowed for better nutrition year-round. Appliances, just like automobiles, were status symbols for a new age of American prosperity.

After recording her first mega-hit song after years of scraping by, country music star Patsy Cline famously said, “Ain’t nobody taking my Frigidaire and my car, now!”

Notice how she mentioned the Frigidaire first.

Got a tip? Send us a note: tips@thedrive.com