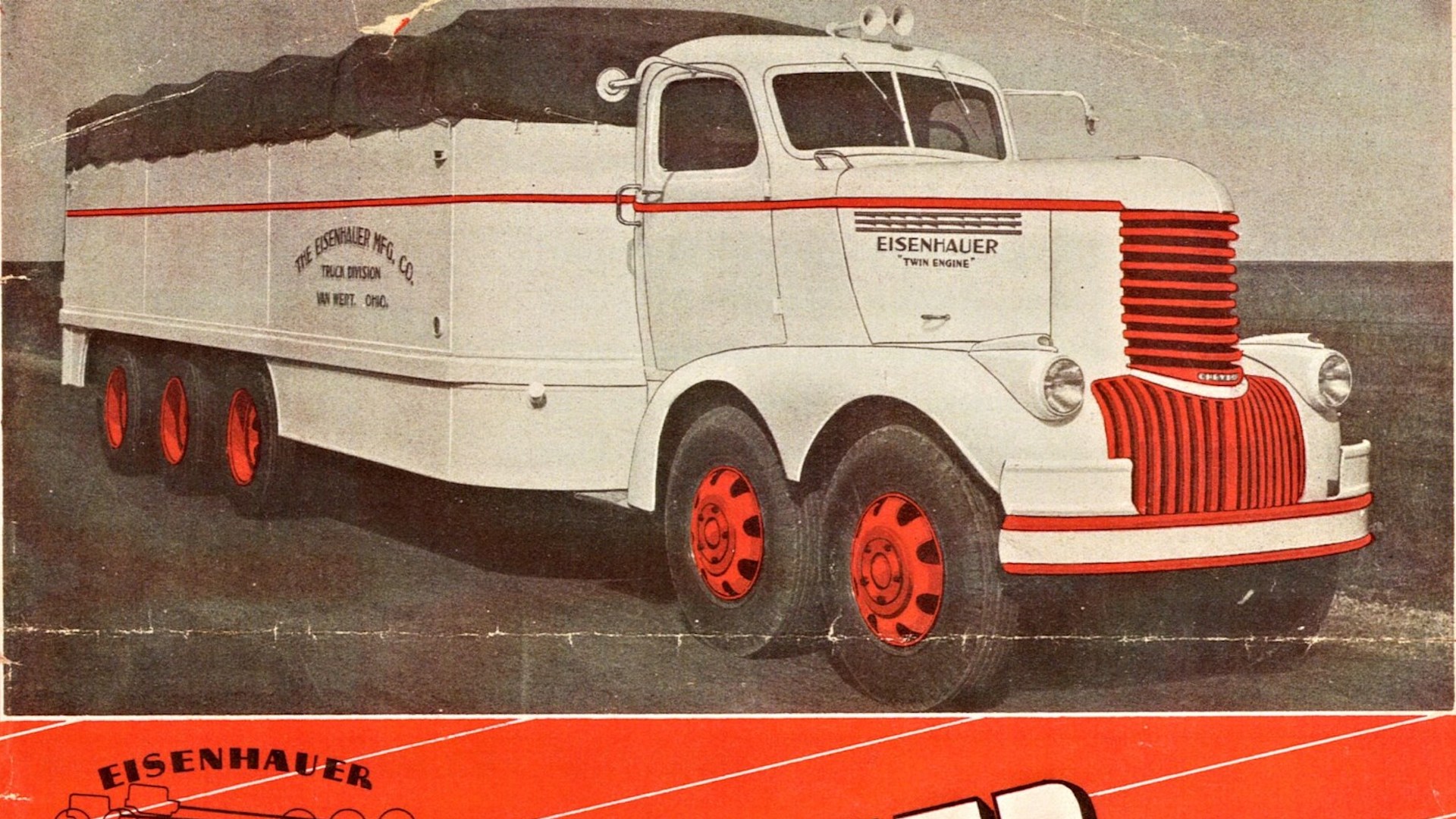

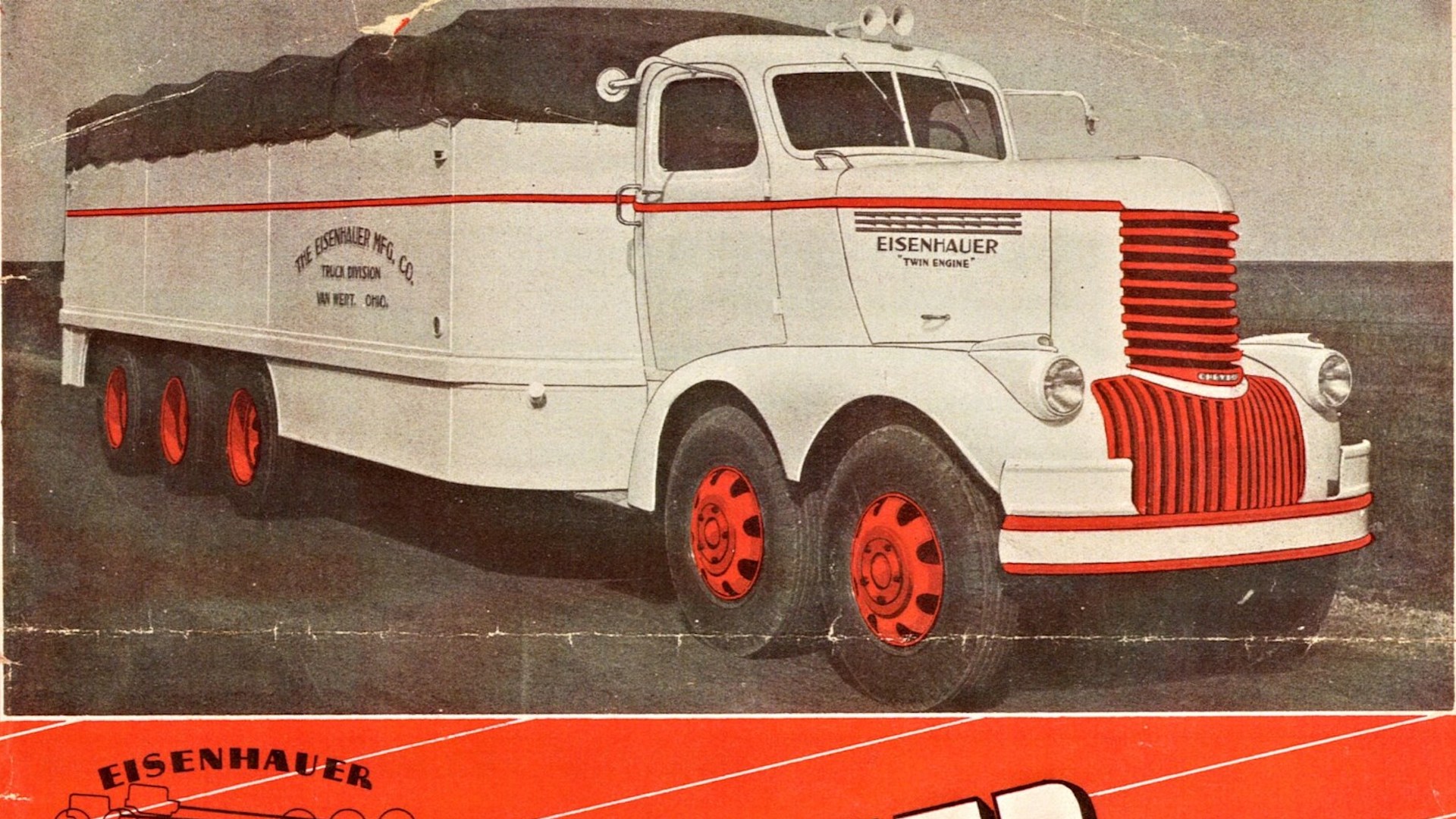

Among other things, the conclusion of World War II in 1945 meant there was suddenly a whole lot less demand for matériel, and that America’s wartime manufacturing industry had to find new sources of revenue. One Ohio-based company, Eisenhauer Manufacturing, decided to try switching from producing tank bogies to building heavy trucks, starting in 1946 with an enterprising prototype with two engines and three steerable axles. The aptly-named Eisenhauer Twin Engine Freighter wasn’t long for this world, but it was an incredibly cool and early example of the spirit of reinvention that would come to dominate postwar America.

And what was Eisenhauer trying to reinvent? The humble semi-truck, of course, which by that time was already a common sight. The Twin Engine Freighter’s dual powerplants were seen as a way to both provide adequate power while carrying a load and economy while traveling unladen, with one engine shutting off for a primitive version of cylinder deactivation. A rigid truck with part-time multi-axle steering, Eisenhauer believed, could be just as nimble but easier to drive than semis, which are tricky to reverse and prone to jackknifing.

Though trucks with multiple steering axles exist today, the Twin Engine Freighter was obviously a failure. But imagine for a second that it wasn’t, that the concept took the logistics world by storm, got copied by competitors and eventually became the mold for heavy duty trucks, the same way Alexander Winton’s 1899 semi-trailer concept set a now-ubiquitous standard. Like any industry, the history of the automobile is strewn with paths not taken. Let’s take a stroll down another good one, shall we?

Triple Steering, Double Engine, One Singular Truck

Eisenhauer assembled its prototype from a pair of medium-duty (or 1.5-ton) Chevrolet trucks, which when glommed together measured 35 feet long, 25 of that being bed. Payload capacity was rated at 40,000 pounds, which would’ve been hauled around by a pair of vacuum-synchronized 235 cubic-inch (3.9-liter) Chevy inline-six engines. One was mounted out front under the hood, while the other sat beneath the driver’s seat in a cab-over configuration. Archived 1946 spec sheets published by the GM Heritage Center rated each at 83.5 horsepower and 182 pound-feet of torque, which they sent down almost entirely separate drivetrains, linked only by common gas and clutch pedals.

Indeed, a single pedal controlled the throttle of both engines, while another actuated their clutches, though each transmission was shifted individually. Presumably, this was done to allow one to remain in neutral, as the Freighter was apparently designed to run on a single engine when unloaded to save gas. Shifting itself was said to be “done by air cylinders” and aided by “differential type synchronizers,” though we have been unable to find photos of the cab to shed light on how that worked. Just speculation on my part, but it may have used pneumatics to automate manual shifting.

From these transmissions, torque traveled to twin Timken two-speed rear axles, the front engine powering the leader of the three, the rear engine the trailing unit, while the center axle remained unpowered. All were duallys, sprung individually, while the rearmost appears to have been mounted on a pivoting subframe, which, combined with a balljoint on the end of the driveshaft enabled rear-wheel steering. It’s unclear how this axle was steered, though it may have simply trailed freely except while reversing, when pneumatics locked it in place. In combination with the two steered front axles, Eisenhauer believed it would give its truck maneuverability comparable to a tractor-trailer setup.

Eisenhauer aggressively paraded its Freighter in front of the public—literally; its prototype led GM’s procession in a parade held June 1, 1946 in Detroit, in honor of the 50th anniversary of local automobile production. It reappeared in Tampa, Florida that September for a trucking show, and then later at the 1949 Michigan State Fair. Widely circulated ad materials boasted that its Chevy basis made 90 percent of its parts serviceable just about anywhere in the country, and depicted a range of body styles, including one truck with an enclosed box and another as a tanker. These, though, were merely airbrushed concept illustrations according to a 2003 issue of the old trucking magazine Wheels of Time that remains the most comprehensive history of the Twin Engine Freighter. There was only one real prototype, which never entered production for reasons the company didn’t disclose and remain unknown to this day.

“Manufacture is delayed because of certain conditions in the industry,” said the company in 1946, as echoed by a 2015 Eisenhauer Facebook post chronicling the truck’s history, labeled “Part 1.” This post was never followed up, leaving the Freighter prototype’s fate a mystery. But it wasn’t the end of the line for Eisenhauer’s five-axle truck ambitions.

Twin Engine Take Two

Just over a decade later, in 1957, Eisenhauer debuted an evolution of the Freighter concept; another five-axle, twin-engine truck called the X-2 (shown here). This one was exclusively a cab-over design and was powered by dual GMC 302-ci (4.9-liter) sixes, sending their 145 horsepower apiece through separate “Hydra-Matic” four-speed automatics. Wheels of Time reported they combined to give the X2 eight forward speeds, though how this worked was not explained. The X-2’s steering was even more complex, too, with hydraulic power steering that connected not just to the fifth axle, but the third as well. Note the lack of a side skirt over the third axle below:

Approximately six X-2s were built, five of which were tested by Detroit-area trucking companies, one of whose test drivers on one occasion reportedly used the X-2’s unique drivetrain to puzzle his fellow truckers. While traveling in a convoy, one of the X-2’s drivetrains broke down, and the truck crept to a stop. After removing the failed powertrain’s driveshaft, the X-2’s driver was asked whether he needed to phone for help. No, he replied, stating he’d coast all the way to his destination. After taking bets on how far he’d make it before running out of steam, he hopped in the X-2’s cab, started its second engine, and proceeded as planned to the befuddlement of the drivers who had just watched him remove a driveshaft.

Eisenhauer, though, couldn’t afford to start volume production of the X-2, and according to Wheels of Time, hoped the U.S. military would bankroll its manufacture instead. It sold a single prototype tanker truck to the Army, which reportedly told Eisenhauer its truck passed field tests, but that production couldn’t be funded due to changes in military budgets. In reality, though, the Army was reportedly never interested in the truck, but rather in testing its unique features; the twin drivetrains, unique suspension, and hydraulically tilting cab (about which little information survives). And any promise these features may have had was overshadowed by the truck’s problems in testing and difficult service.

The X-2 prototype reportedly arrived with significant defects, which were fixed on-site but set the tone for the tests to come. On the frame-twister course, the X-2 didn’t get past the first stage before the front suspension failed, its leaves separated, and its mere 9.5 inches of ground clearance proved inadequate. Driven on a 30-percent sidegrade (or 16.7 degrees), the X-2 was already close to tipping over without a load, and it was about here when engineers discovered the cause of its inexplicable maneuverability problems.

These were chalked up to failed lead suspension arms on both drive axles, whose welds split. Replacements from Eisenhauer reportedly took 100 labor hours to install, far too much time to the Army, and they didn’t fix the problem of serious tire scrub while reversing, which could cause the truck’s engines to stall. At some point, technicians reportedly also found an internal hydraulic leak in the rear-axle steering circuit, though they reportedly believed the X-2 would’ve driven as intended had that not been the case.

Into the Dustbin of History…and Probably for the Best

Eisenhauer wound up repurchasing the X-2 as surplus, before leaving it outside until 1980 when a local farmer bought it to repurpose its tank. The fate of the other five and the original 1946 prototype is unknown, though it’s not hard to surmise why they didn’t stick around. They don’t seem to have been reliable enough for long-haul truck duty, which in combination with complex service may as well be a death sentence for a commercial vehicle. And more speculation on my part, but I doubt it would’ve been capable of highway speeds when fully loaded. Carrying its maximum of 40,000 pounds, the 1946 prototype would’ve had a power-to-weight ratio in the neighborhood of eight horsepower per ton, or less than an M4 Sherman.

So, it probably moved like a tank, even if it wasn’t built like one. For a commercial vehicle, that’s no winning combo, though it’s the kind of thing that’d make it the crown jewel of a motoring museum. Let’s just hope somebody out there knows what happened to the Eisenhauer Freighter, and can tell us whether it ended up in the scrap heap, or survived to become something like a bus line’s promo vehicle.

Know what became of the Eisenhauer Twin Engine Freighter or X-2? Give me a shout at james@thedrive.com.