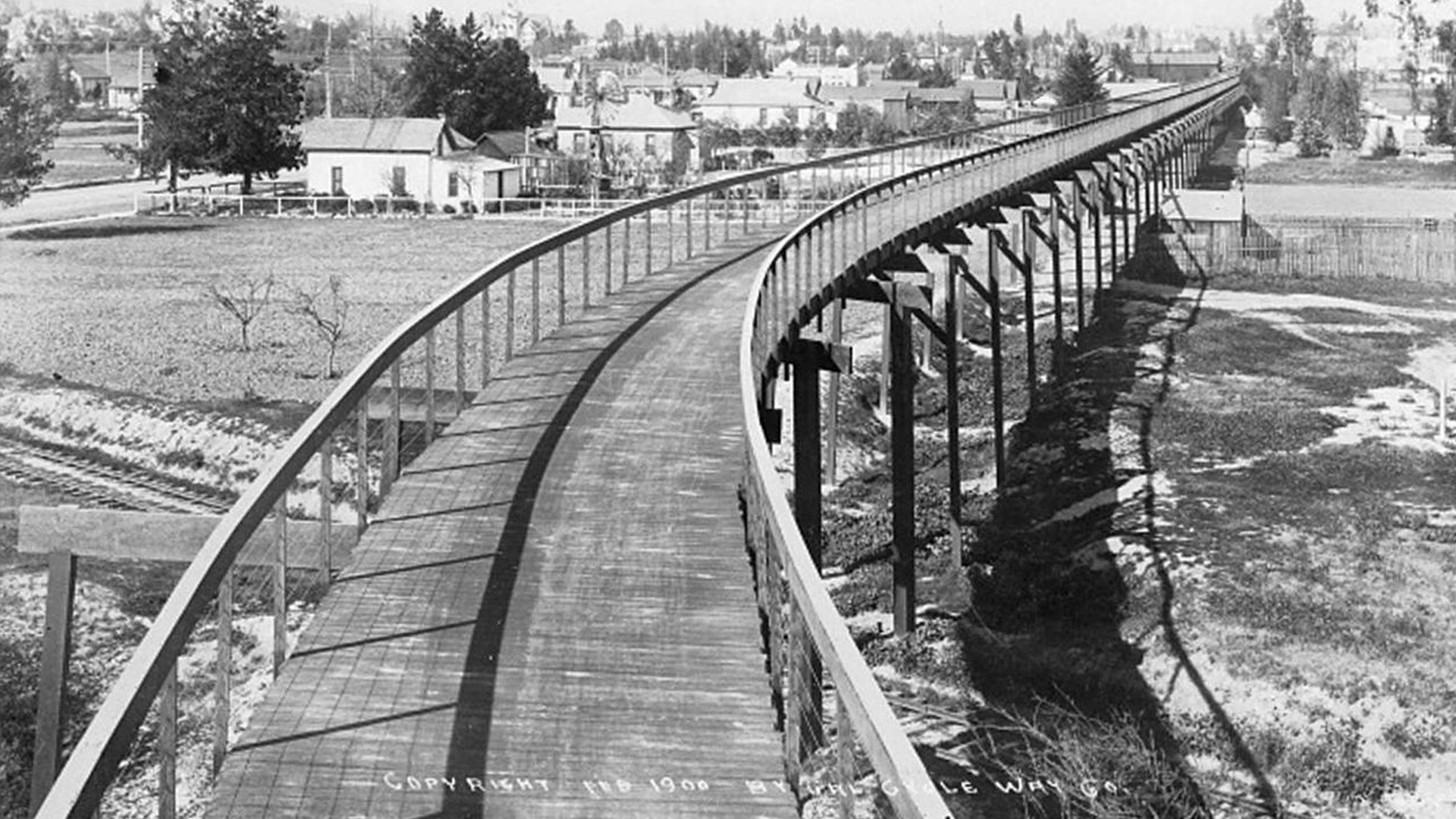

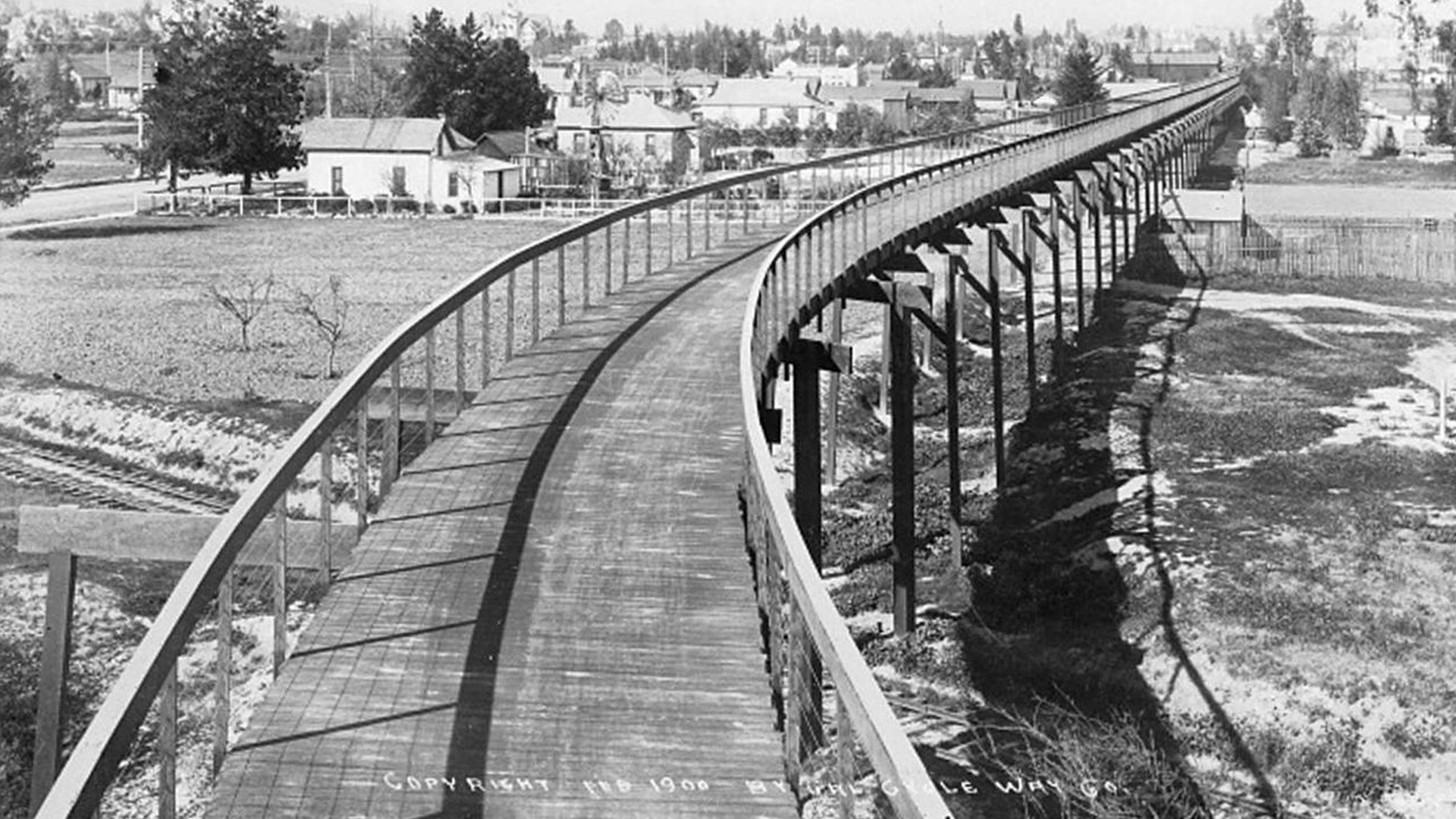

The year was 1899 when the U.S. dreamt up its first elevated cycleway; a sharp-witted idea to connect Pasadena, California to downtown Los Angeles via a raised wooden toll road constructed solely for bicycles.

It was genius, and Pasadena’s mayor at the time, Horace Dobbins, was hailed as an innovator for conceptualizing it all. Publications claimed the California Cycleway’s effects on industrial activity would single-handedly increase the country’s prosperity. To put it into perspective, the first interstate highway wouldn’t be built for another half-century in the U.S.

Well, we now know that’s not how it played out, but the idea was rather good. Cyclists would travel along the Arroyo Seco and reach their intended destination quickly, free from horses and Los Angeles’ newly built trolley system that began operation just a few years prior. The development of the cycleway happened during the golden age of bicycling, and Pasadena’s entire infrastructure was built around the two-wheeled contraptions.

Then came the introduction of the automobile in the early 1900s. By 1908, Henry Ford introduced the Model T and Pasadena’s rich pedal-centric culture began to shift. Bicycle shops soon became motorcycle shops, and subsequently turned into four-wheeled automobile dealers.

Needless to say, Ford’s creation was a hit and the cycle-built infrastructure soon gave in favor of cars.

A century later, Los Angeles has made the top 10 list for most congested cities in the entire country—though the hour-long bicycle commute from Pasadena still only takes 20 to 25 minutes by car.

While the rest of the modernized world seemingly blended its automobile and pedestrian infrastructure, the U.S. ate up its newfound love for vehicles. Today, that leaves major cities reworking their streets for more alternative forms of travel, whether it be cycling or e-scooters.

Should elevated cycleways make a comeback? Some of the world thinks yes.

China, for example, sandwiched bike lanes underneath its overhead Bus Rapid Transit lanes in the city of Xiamen. This led to a 4.7-mile (7.6 km) stretch of bicycle-only pathway that citizens can use for the exact same safety reasons the California Cycleway was conceived, albeit a bit more modernized since it stretches across a six-lane highway and two smaller (yet busy) roads.

BMW got into the action next with its E³ Way concept in 2017. The automaker envisioned a modular toll road for two-wheelers set up in busy city centers. The concept put cyclists together with e-bike and e-scooter riders, giving a raised platform for easy travel. The path would ride alongside busy highways and bridges, yet remain covered to keep the riders free from noxious emissions while still providing a safe and direct route to busy hubs around the city. And, as an added benefit, the roof could be equipped with solar panels to provide electricity for charging stations at designated platforms.

The biggest hurdle has to be the massive cost to construct these elevated structures. The price of the Xiamen cycleway remains a mystery, but even transforming on-ground pavement into bicycle-friendly pathways comes at a mighty expense. France previously pledged $350 million (300 million Euros) to create over 400 miles of “pop-up” cycleways in Paris, with Mayor Anne Hidalgo noting that the city planned to eventually remove 72 percent of its on-street parking which would make the city more cyclist-friendly.

Is there a case for building these types of elevated cycleways into new public infrastructure? Sure. Cars are larger and heavier than ever, and there are no signs of that slowing down anytime soon. Creating more alternative options for commuting in urban infrastructure will likely help encourage people to commute differently, and bicycle sales are certainly booming. But the real question to ask is: Do the benefits truly outweigh the undoubtedly massive costs of the project?

Got a tip or question for the author? Contact them directly: rob@thedrive.com