“I drove a Grand National around all day,” Sung Kang tells me one Thursday evening over the phone. He’s talking about his 1987 Buick Grand National. It’s black. Its name is Buddy.

“Yeah, it’s all sorted,” Kang goes on. “People want to steal that car, so I went and put on a new quick-release steering wheel. It’s slowly becoming a JDM-like muscle car. That’s the beauty of LA—I was just pinching myself today.” He’d called his friend in the morning and talked about how he wanted a quick-release steering wheel for the Buick he could just carry off if he walked into a store. His friend had one, so he drove down and had it installed.

“It just looks money. It looks so sick,” Kang says. “And all the employees were just hovering around the car, salivating. That’s amazing: A bunch of strangers—different ages, different ethnicities, different classes, different income brackets, different positions—are all there smiling and hanging, being cool with each other, over a car. I brought this Grand National over to put a quick-release in and made everybody’s day. It’s just so weird, simple, right? Beautiful.”

[May is Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month. Here at The Drive, we’re celebrating it by lifting up and highlighting AAPI voices in the automotive space. Our hope is that in driving visibility, we can help make the car community an even more welcoming space—to convince those who perhaps have not always felt like they belonged that they absolutely do belong here. Diversity in perspectives and backgrounds only strengthens the group as a whole. It is why representation matters.]

If you didn’t know any better, this could have been Kang describing a deleted scene from The Fast and the Furious: Tokyo Drift. Kang famously plays Han Lue in the Fast franchise, a character who will make a comeback in the upcoming F9 film that will hit theaters on June 25. I used to wonder if Kang seemed so cool because he’s spent over a decade playing Han. Now I know, indisputably, it’s the other way around.

“As an actor, I rejected the idea of being known for one character for a while,” Kang says. “But Han only represents good things—positive things—of what people would love to have in their older brother or sister: loyalty and inclusiveness, not having to worry about money, having cool cars. All that stuff.”

For Kang, being Han allowed him a way to both scratch his car hobby itch and give the fans what they want. “It was interesting being able to walk in Han’s shoes in the real world. It gave me access to the car community,” Kang explains. “You basically be enthusiastic and cool, just like the simple characteristics Han has. Be inclusive, don’t be an asshole, don’t judge people based on their money and how expensive their car is. Just be chill. People love you, you know? So you have a key to the city.”

Fans can rank their favorite Fast film amongst themselves, but the perennial themes that safeguard Tokyo Drift against the test of time are undeniable. Besides the authenticity of the tactical stunts and the respect for drifting culture, the story was one of family, loyalty, friendship, brotherhood, and doing the right thing “within a world of make-believe,” as Kang calls it.

When Tokyo Drift came out in 2006, it was already rare to see Asian representation on the big screen that wasn’t Jackie Chan or Lucy Liu. It was even rarer to see Asian representation that was not being forced to do campy Asian stereotypes or talking with racist accents. In this regard, Han was a breath of fresh air. He wasn’t Asian as seen through a white lens. He wasn’t a nerd or a kung fu fighter. His garage was a place you found yourself wishing you could hang out in, and him someone you aspired to be.

Now, 15 years later, I ask Kang if he knew at the time what sort of impact he’d have on other Asian automotive enthusiasts.

“No, not at all,” he says. “The idea of it blowing up and actually having an impact was so far removed from my and Justin [Lin]’s thinking because it was a matter of survival at that time. It was like, ‘Man, I’m lucky to have a job.’ That was a rare and lucky opportunity we got to be a part of and it just so happened there was success. The stars were aligned.”

Lin, as Kang tells it, was insistent that Han’s character stayed three-dimensional and would not be there “for an Asian reason.” He was there to protect Han. The resulting cultural impact was a byproduct that came later. It’s something Kang regards as a gift. “The bonus is you’re a part of a community that you looked up to because of a movie you were in as an actor. All of a sudden, you’re Han. You’re an idea people need.”

Kang grew up in Georgia, where he describes American cars and car enthusiasm as “part of the fabric of everyday life.” He watched the people in his neighborhood working on their Impalas, Camaros, Firebirds, and Thunderbirds. “They changed the oil at home. There was a whole ceremony of buying a car. They took care of their cars, so I had neighbors I was able to watch and learn the process of restoration from, and understand badging and the difference between different models,” he says.

From the movies and TV shows that inspired him to pursue acting—Knight Rider, Dukes of Hazzard, Bullitt—came also a love for the automobile.

“I always found the idea of a car—cool cars, certain cars, race cars, sports cars—just super romantic and for the wealthy and privileged,” Kang says. “We didn’t grow up with that opportunity to have those types of toys. I never had money to have hobbies like cool cars and drift cars and stuff.”

Kang’s entry into the car community didn’t start until later on in life. Up until then, “I looked at it from afar, like in a magazine. I couldn’t afford to do that stuff and I didn’t have the time,” he says. “I was hustling to be an actor. I wanted to have a voice and I went after it. People think you wake up and you’re in a movie. It doesn’t work like that.” Kang recalls having to work a bunch of jobs, going to acting school, doing theater, appearing in free and short films, going to audition after audition (and never getting many of them). “Each job you get, you learn what not to do, what to do, and over time you build your resume.

“Then you put the color on it,” Kang continues. “It’s statistics and just less opportunities, but the people in the system today are changing things, so we’re in a great place. But struggle and humility—understanding how to serve people, that you have to work for your money, being turned down—is a necessity. You have to go through a crisis, I think, to be an artist that is interesting.”

Kang’s made it. He has impact now. A voice. But he doesn’t forget what it took to get here. “Challenges are part of the whole journey. Those are the tracks that lay down where you are today and your perspective,” he says. “You have to play that role of the actor, a famous person, or celebrity. You have to create it because no one teaches you how to be that. It’s all relative to you. What’s important to me? Cars. But how do I parlay influence from Hollywood into that, use it as a tool for positive contribution, opposed to just like for me? Like, ‘Look at me. I’m doing cool stuff. I have cool cars’? It’s hard to exist that way on a personal level for me.”

So Kang uses his influence to build a community around himself.

“Building a car with a team of people is like making a movie,” he explains. “I’m just a piece in the machine, and I have to know what exactly my contribution is. Influence helps. You build a Z, and your name is Joe Schmo, it’s a Z, right? But then I build it and all of a sudden it creates commerce for everyone. The parts are sold, there’s enthusiasm, more people come into the community, and there are more cars being built.

“There’s more sharing of the good guys. I don’t know shit about cars. I can’t build a car by myself, but I do know talented people. Good people. That’s a skillset I have. I know how to bring them together. I know how to make just the mundane idea of building a car super exciting.”

In Kang’s eyes, it’s important to inject excitement and enthusiasm into the car community. “It’s something that people need, you know what I mean? Who gives a crap when a car’s getting painted? But I make it exciting because Han shows up.”

Kang’s personal automotive endeavors are all detailed via his site Sung’s Garage, which is also splashed across Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube. It’s a corner of the car internet that feels instantly accessible and relatable—one that gatekeeps no one and makes everyone feel like they have a place in the automotive community. This is absolutely by design.

It’s clear Kang is hyper-aware of the influence he has, so he does his best to uplift and encourage others. “I realize the power I have when this idea of Han validates your car,” he says. “Like, some kid comes up and they have whatever car. It can be a cool one, new one, old one, a piece of junk. If I say, ‘That’s a pretty cool car,’ it makes their day. That is an amazing gift, to be able to make somebody happy by saying, ‘Your car is pretty sweet, dude.’ That’s crazy, you know? They’re so happy, like it validates their existence in the car community, the fact that I give them a thumbs-up. It’s so weird.”

Interactions such as these must have happened to Kang countless times over the course of the years, yet he still sounds delighted and slightly disbelieving when he talks about it.

“I know it’s not normal,” he responds. “I mean, even if it happens 10 times when I go and do car stuff, I still live day by day in my regular world and in Hollywood. It’s nice to see people light up because of a car.”

Kang doesn’t target the usual suspects when building up his personal car community. “For me, it’s always the underdog and the marginalized,” he says. The people nobody wants to have lunch with and are still looking for their place in the world, in his words.

“I think that’s why my friends are all kind of misfits,” he continues. “They’re like these weird bodies, and you would never expect them to be geniuses in their field, or heroes. They’re like cowboys and women of honor, [with] simple principles that happen to be people of color, that maybe don’t speak English that well.”

Kang says his mentor is Erick Aguilar, a half-Mexican man from Guatemala and is like “the Mr. Miyagi of Datsuns.” Aguilar is the one who teaches Kang everything.

“I love hanging out with people like him because nothing is polished,” Kang says. “His shop is not super fancy. It’s in the hood. But the kids and people that come through are, like, gardeners and the sons of immigrants, the housekeeper that just wants to get into cars but doesn’t know anybody that can teach them JDM. Here, there happens to be a guy who speaks Spanish and will buy you ice cream and answer any question. It’s like a fucking movie.”

Kang owes it to the Fast movies and Han that he has access to places like Aguilar’s shop. “Naturally, I’m inquisitive and curious,” he says. “I’m always looking for an older bro. I’m looking for my own Han. And so when I find those guys, it inspires me to speak to the underdog. That’s why I don’t fuck with supercars and Ferraris. It’s not about balling and flossin’. It’s about relatability. It doesn’t matter what you look like or where you’re from, or if you’re not Asian. It’s okay to be messing with Datsuns, but if you’re going to do it, go to the highest level. Be a master.”

From his own experience, Kang recalled just needing to see his face on the screen to believe he could be an actor. Seeing people who look and talk like you existing in places you would want to inhabit—in professional sports, on stage, behind the wheel of a car—does wonders for the possibilities you can imagine for yourself.

“If I want to be a movie star, I need to see that guy,” Kang explains. “I know a lot of dudes in the [Latinx] community—they want to mess with Datsuns but there’s this kind of, like, resistance, because they’re like, ‘Is this a community for me? Will I be accepted?’” But with people like Aguilar opening the doors, the community becomes just a bit more welcoming to others.

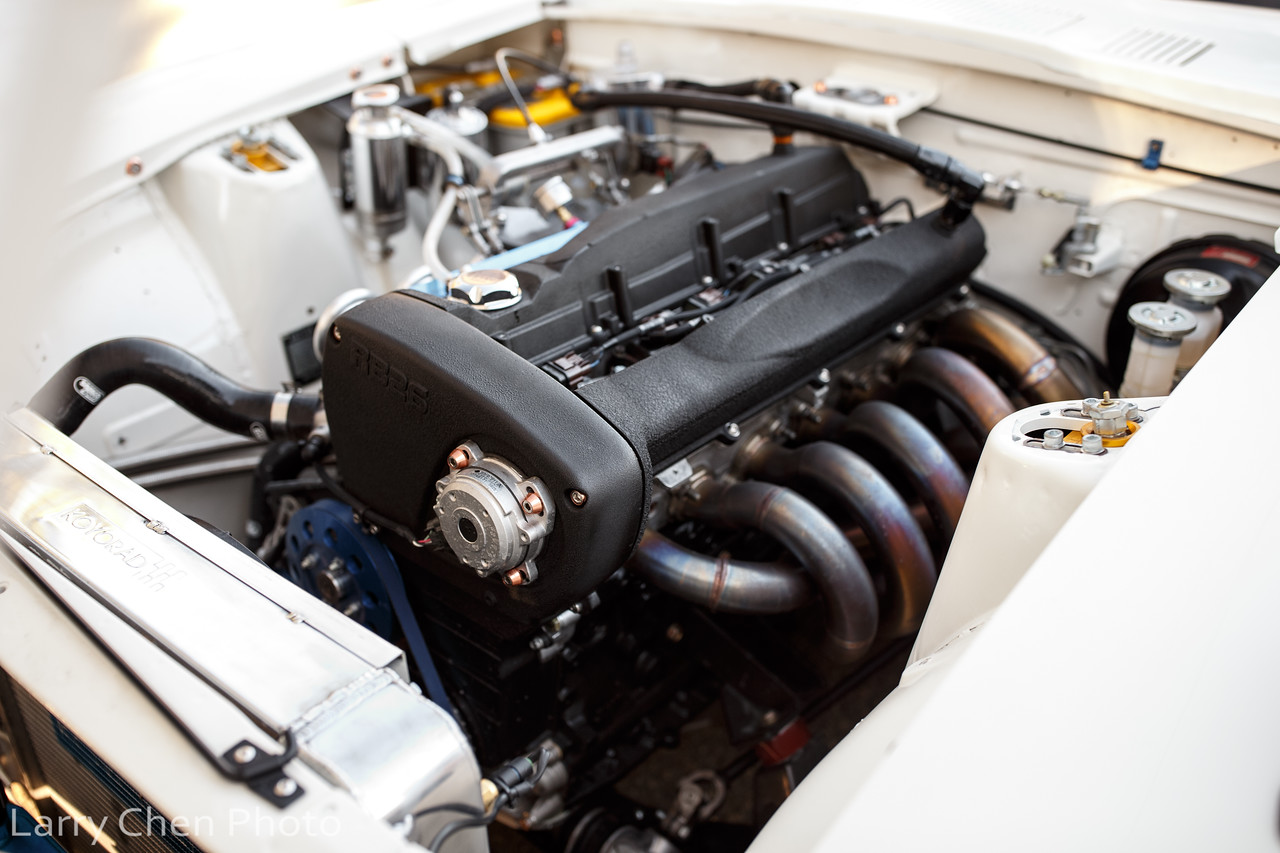

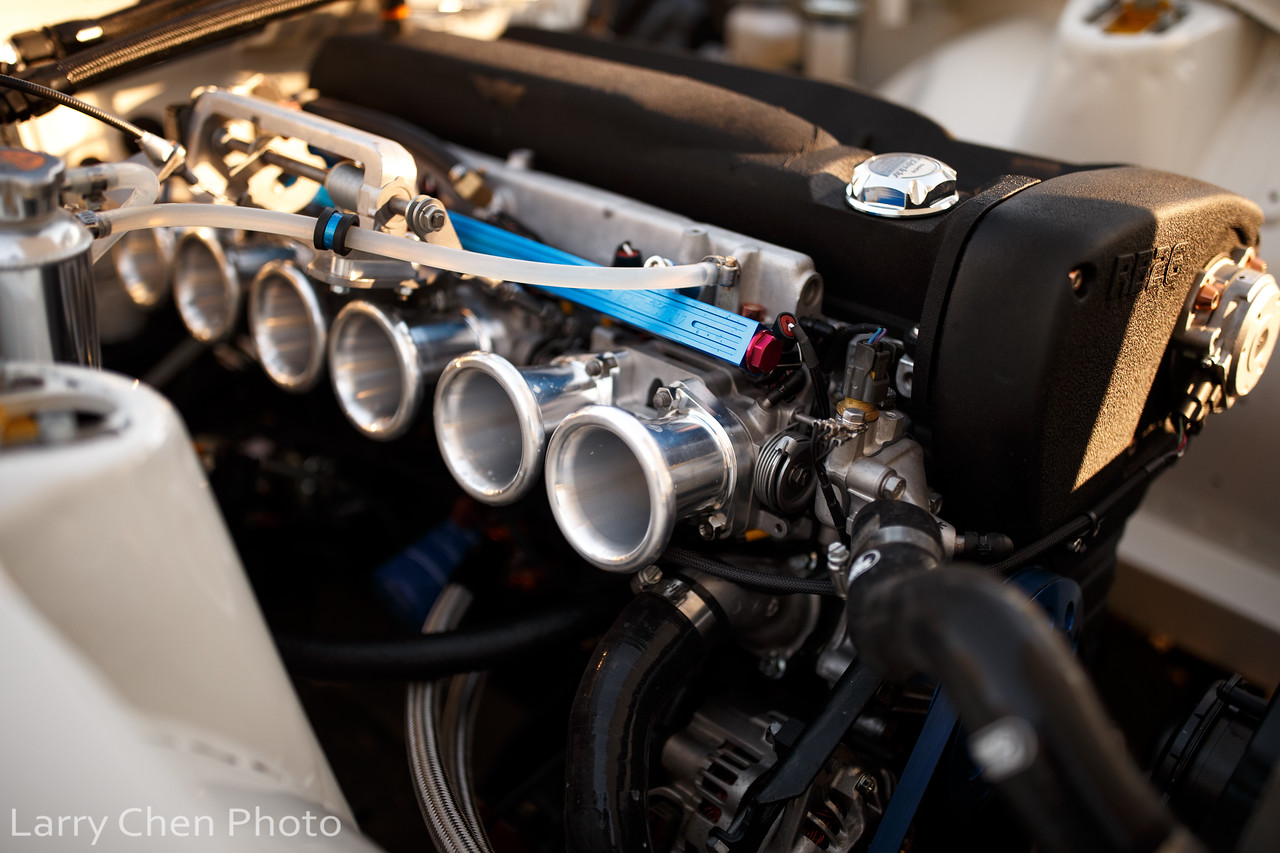

Currently at his garage at home, Kang has a 1974 Porsche 914 with a V8 swap, which he calls his “COVID project.” It was someone’s unfinished dream that Kang bought off a used car dealership. Aguilar and a bunch of Kang’s friends went through it and got it running again. “They all got together and put their brains together to get this thing back on the road. It’s so beautiful,” Kang says.

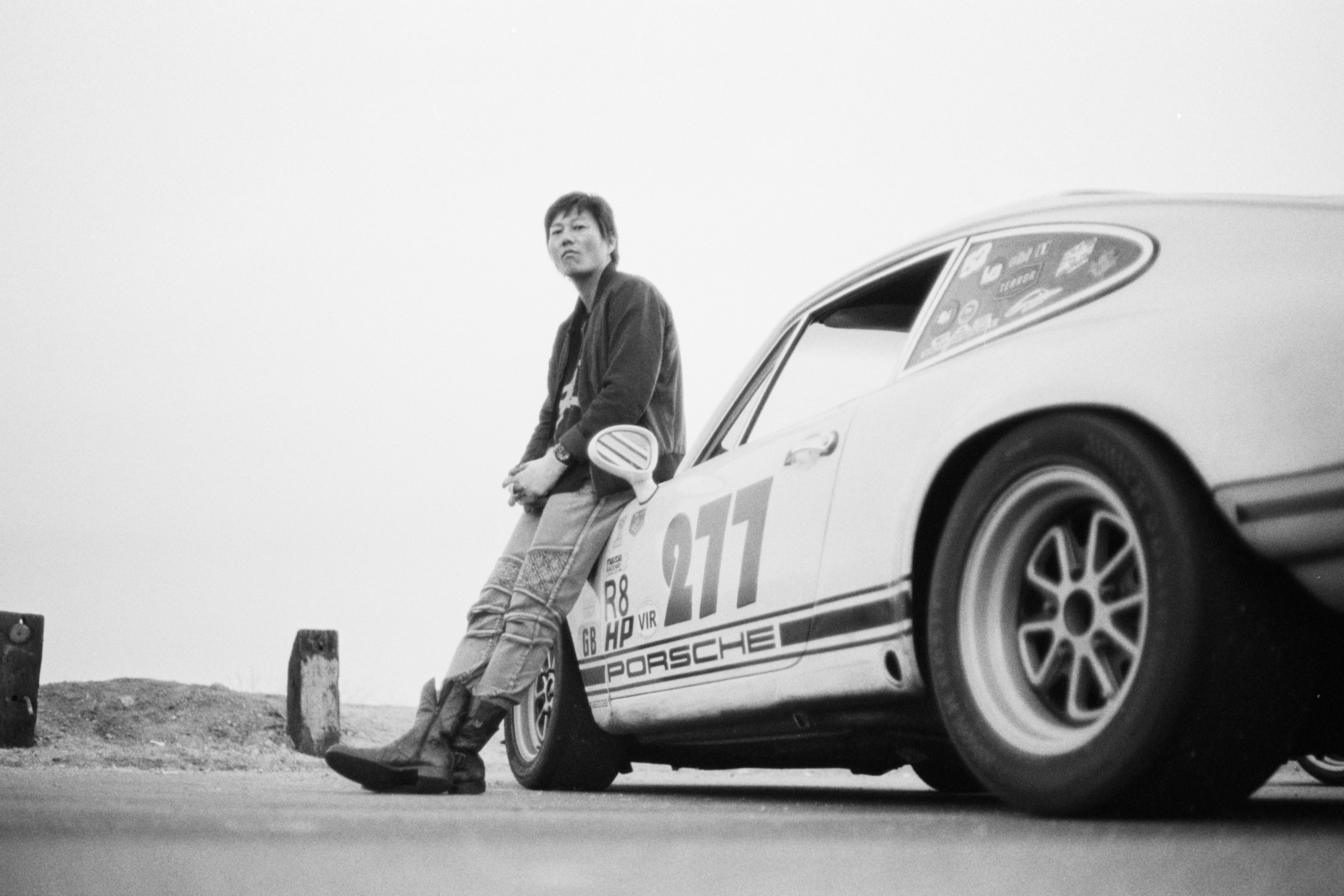

Then there’s a 1971 Datsun 240Z—an East African safari homage. Its name is Doc. “I call it the master class in a 240 resurrection in every way,” Kang says, ticking off everything he’s done to it. “From body to paint, rust repair to full engine rebuildings, but then making everything plus. So I called the whole car the 240Z-plus.”

Finally, there’s the Grand National, which had been sitting since 2006 when Kang found it. (“It was all fucked up.”) He recalls the special feeling of getting the Buick running again and showing it to its original owner to get approval that he’d passed the car off to the right people.

The Fugu Z—a beautifully modified 1973 Datsun 240Z that was originally found on Craigslist—lives over with GReddy Performance Products and gives Kang a reason to go hang out with Ken Gushi and Kenji Sumino, GReddy’s president.

The cars give Kang “places, pods, and tribes to go and hang out with,” he says. “That’s what I love, is that eventually they all connect and then they help each other. In Hollywood, you can feel so alone because it’s project by project.”

Building that community and base are important to Kang. “You need community. You need a base. You need something to go back to and just say, ‘These are real-life problems, but we’re pretty blessed to get to mess with some dope cars and create.’ Imagine,” he says, “I’m dead 100 years from now and some 13-year-old looks at that car, wherever it is. They talk about this guy, who was the actor in this Fast movie long ago. When we’re dead, hopefully that car lives on. And that’s awesome. A car build is like getting to leave a statue.”

More recently, though, some of those real-life problems have caught up with Kang. He made an appearance at the Stop Asian Hate rally and drive with Sean Lee a few weeks ago but told me, prior to that, it was difficult for him to speak on the topic or presume to wear a cape of justice. He’d seen the news and the social media posts about the anti-Asian wave of violence and considered himself far removed from it—until he suffered a racial attack about a month ago.

“Three dudes started calling me chink,” Kang recalls. “It was going to get very violent quickly, and it just worked out that no one physically got hurt. But it was like a cancer. I went home and it turned into hate. And then for about a month, I was walking like a shell of myself going, ‘Where do I exist? I don’t belong.’ I thought everybody was cool with me, but these dudes calling me chink with so much hate and venom in their eyes based on what? Because of my eyes?”

As a 50-year-old man, Kang thought he’d achieve a place and position in life where he didn’t have to deal with that anymore. The run-in showed him that the hate is still “right in [his] front door.”

Kang remembers waking up with a flood of guilt. He started questioning everything, calling his social media “all this bullshit.” He wondered, “How am I actually contributing to these real-life issues? I’ve been walking around like in a daze—delusional in Hollywood la-la land.”

As Kang describes it, borderline depression and self-doubt followed, which swung back into anger, fear, paranoia, and finger-pointing. He even caught himself wondering who the enemy was while at work.

But that’s not who Kang is and that’s certainly not the kind of person he wants to come off as. There are people he doesn’t want to let down. He doesn’t ever want someone to meet him and think, “Oh, that’s the actor from so-and-so. Well, he’s kind of distant, and he’s defensive, and he’s a little paranoid, or he’s a little to himself.” Or, “He’s not inclusive, and he’s not cool. He’s not the Han that we think.”

This makes nothing better, Kang insists. “That’s actually just spreading the cancer of negativity. It’s so fucked up. You go, ‘Somebody’s trying to bash your head in because you’re Asian?’ There’s no rationale to that. It’s just fucked up—devil evil shit—so how do you rebound from that?”

Kang sees himself as the guy who starts conversations and makes people eat chocolate and enjoy the romantic notion of being part of Hollywood. He felt the hate-filled altercation taking that away from him and realized that’s how they win.

“This hate is so venomous, and there’s no rhyme or reason to it,” he says. “But the answer is not divisiveness and looking at each other with suspicion or as the enemy. It’s a cancer that you have to beware of. If you drink that thing, man, it fucks up your life. I feel lucky I have family and friends that have been there with me to give me perspective and go, ‘Okay. You do have a place. You do have family. You do have community. People do want you around. Your ethnicity and your face is not a negative. It’s just shit that we’re going through right now.’”

So what is there to do? “You still have to keep your chin up, your chest out, and you have to be the best version of yourself. It just happens that you’re Asian. That’s how we change things. Strive to be even more positive. That’s the only answer. Positivity is the answer. There is nothing else.”

We all need our heroes and there are people who indisputably look up to Kang as theirs. “It’s a blessing and a privilege to be able to walk as a hero, and to try to be a hero in life,” he says. Kang doesn’t call himself a hero, specifically, but he does want to set an example, to be seen as someone others would want to be.

Earlier in our chat, Kang talked about building a car as a lasting statue. But it’s clear the real statue is the legacy he’s already created.

Got a tip? Hit me up at kristen@thedrive.com