Good Monday morning and welcome back to Speed Lines, The Drive’s roundup of what matters in the world of cars and transportation. Somehow, we are halfway through June, although it feels like we’ve been living in 2020 for 1,000 years. Today we’re talking about the plot to take down Nissan-Renault megaboss Carlos Ghosn, delivery robots and the new “normal” for automakers.

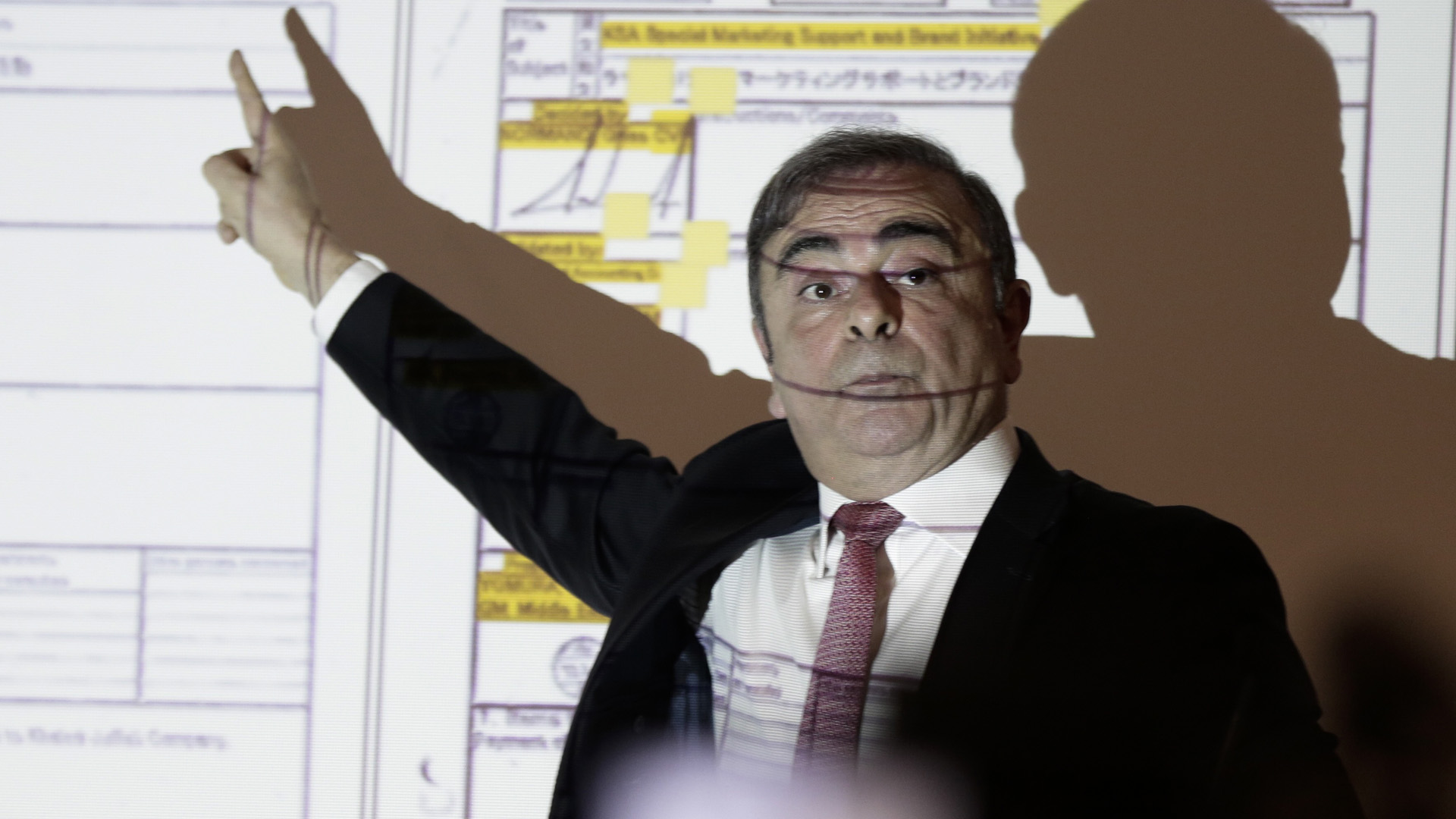

The Plot To Dethrone Ghosn

Carlos Ghosn, who once ran one of the world’s largest car companies and is now in exile in Lebanon after being smuggled out of Japan in an instrument case, always said he was set up. He maintained he had become unpopular within Nissan, one part of the car empire he ran, as he sought to further cement that company’s ties with its alliance partner, Renault. Both Nissan officials and Japanese authorities disagreed, saying Ghosn was in fact misappropriating company money and underreporting his income, leading to criminal charges as a result.

But Bloomberg has a bombshell story today featuring internal communications at Nissan that seem to legitimize the idea of a plot against Ghosn; a plot that began almost a year before he was arrested, orchestrated by senior managers who wanted more autonomy on the Japanese side of things.

From that story:

At the center of those discussions was Hari Nada, who ran Nissan’s chief executive’s office and later struck a cooperation agreement with prosecutors to testify against Ghosn. Nissan should act to “neutralize his initiatives before it’s too late,” Nada wrote in mid-2018 to Hitoshi Kawaguchi, a senior manager at Nissan responsible for government relations, according to the correspondence.

[…] On Nov. 18, 2018, the day before Ghosn was seized on a private jet at Tokyo’s Haneda Airport, Nada circulated a memo to then-CEO Hiroto Saikawa, according to people familiar with the document. Nada called for termination of the agreement governing the alliance and the restoration of the Japanese company’s right to buy shares in Renault, or even take it over. Nissan also would seek to abolish the French automaker’s right to nominate Nissan’s chief operating officer or other more senior positions, people familiar with the memo said.

[…] Nada told CEO Saikawa in April 2018 that Ghosn was becoming increasingly agitated about Nissan’s performance and comments by his handpicked successor, who said he saw “no merit” in a merger between Renault and Nissan. “He can create a major disruption and you may become a victim of it,” Nada wrote to Saikawa. The following month, Nissan issued a profit outlook well below analysts’ estimates.

Nissan and Renault (and now Mitsubishi) have a deep contractual partnership, but they are not the same company; no merger ever took place. It’s a partnership with a great deal of power struggles and friction, complicated at times by the French government’s 15 percent stake in Renault, because socialism. Though it’s been a largely successful alliance over the past 20 years, the Japanese side of it has wanted more control and authority. The working theory is that Nissan managers worked to oust Ghosn by any means possible when he sought to further cement ties between the two entities.

Obviously, worth a read in full. And the question now is, what does all this mean for Ghosn’s charges? It’s unlikely those are going anywhere.

Has Autonomy Found A Business Case With Delivery Robots?

The COVID-19 recession has torpedoed a lot of capital meant for the development of autonomous vehicles. But even before this year, AVs had a questionable value proposition. Every automaker and tech company wanted in on that space, but no one was really sure how it would actually make money.

There’s always opportunity in crisis, however. And COVID-19—along with the public’s general reluctance to go outside, or into crowded stores, or to gather in large groups—may pave the way for autonomous delivery robots as a useful and lucrative use of that technology. Basically, with retail dying anyway and people not wanting to go out, delivery vehicles may be the answer to the AV moneymaking problem, according to a fascinating new story in Automotive News:

“The time for delivery robotics is here,” said Reilly Brennan, general partner at Trucks Venture Capital in San Francisco. “If you can handle a handful of shopping bags at a decent speed, this is the time for that. It wouldn’t surprise me to see some robotaxi startups shift to parcel and freight.”

[…] Ford has said it will postpone its launch of a commercial AV service that offers both passenger and package-delivery components so it can recalibrate those plans because of COVID.

“We can’t ignore the change in consumer behavior we have seen during COVID-19,” said John Rich, director of autonomous vehicle technologies for Ford Autonomous Vehicles. “It has impacted everything, from the way we work to how we shop. This change in consumer behavior, whether permanent or temporary, is something we must fully understand.”

It’s not a guaranteed thing, and it assumes we’ll be living with COVID-19 (or similar pandemics) for a long time. But it has potential, probably more so than making robot passenger cars or robot taxi cabs. Fully 34 percent of U.S. vehicle miles traveled are for commercial activity, and 15 percent is for personal shopping; all of that could shift to autonomous deliveries if we’re going to be stuck inside long term. Worth a read in full.

The New Normal May Mean Fewer Choices

There’s a lot to digest in this Automotive News story about the new “normal” in the auto industry: supply chain disruptions, safety protocols, strong consumer demand for trucks and so on on. But the part that stands out to me is the cost-cutting efforts we’ll soon see from every automaker now that we’re fully in a recession.

What that means, according to General Motors’ own CFO, is less complex lineups and less configuration and customization among models. Automakers will prioritize the vehicles, and the packages and options, that are guaranteed to sell. In other words, don’t expect a lot of risk-taking anytime soon. From the story:

Parts shortages because of the pandemic might motivate automakers to reduce the complexity of their lineups and prioritize configurations that sell quickly. For all automakers operating in the U.S., there were more than 605,000 configurations built in 2019, excluding vehicle color, according to J.D. Power. Thus, each unique configuration accounted for an average of only 22 retail sales.

Unwanted configurations usually sit on a dealership’s lot until they can find a buyer with the help of generous incentives at the end of the model year. GM said it has begun eliminating configurations and aims to reuse and share more parts across brands and segments. The simplification effort could be a long-term strategy to cut costs, [GM CFO Dhivya] Suryadevara said.

“We’re just scratching the surface of that,” she said. “And as we go forward here, as the market continues to get more competitive, we’re going to have to make sure that we are as efficient as we can be.”

Having said that, the part about sharing parts across brands doesn’t bode well for Cadillac, for example, which had already been struggling not to be seen as nice Chevrolets anymore.

On Our Radar

JLR parent Tata Motors sees weak first quarter as lockdowns hit sales (Reuters)

Tesla’s US-made Model 3 vehicles now come equipped with wireless charging and USB-C ports (TechCrunch)

Volkswagen expects very bad second-quarter, positive 2020 adjusted operating profit (Reuters)

Read These To Seem Smart And Interesting

Internet Archive Will End Its Program for Free E-Books (NY Times)

Meet the Gun Club Patrolling Seattle’s Leftist Utopia (The Daily Beast)

U.S. Blood Reserves Are Critically Low (WSJ)

Your Turn

Carlos Ghosn: Was this all a setup?