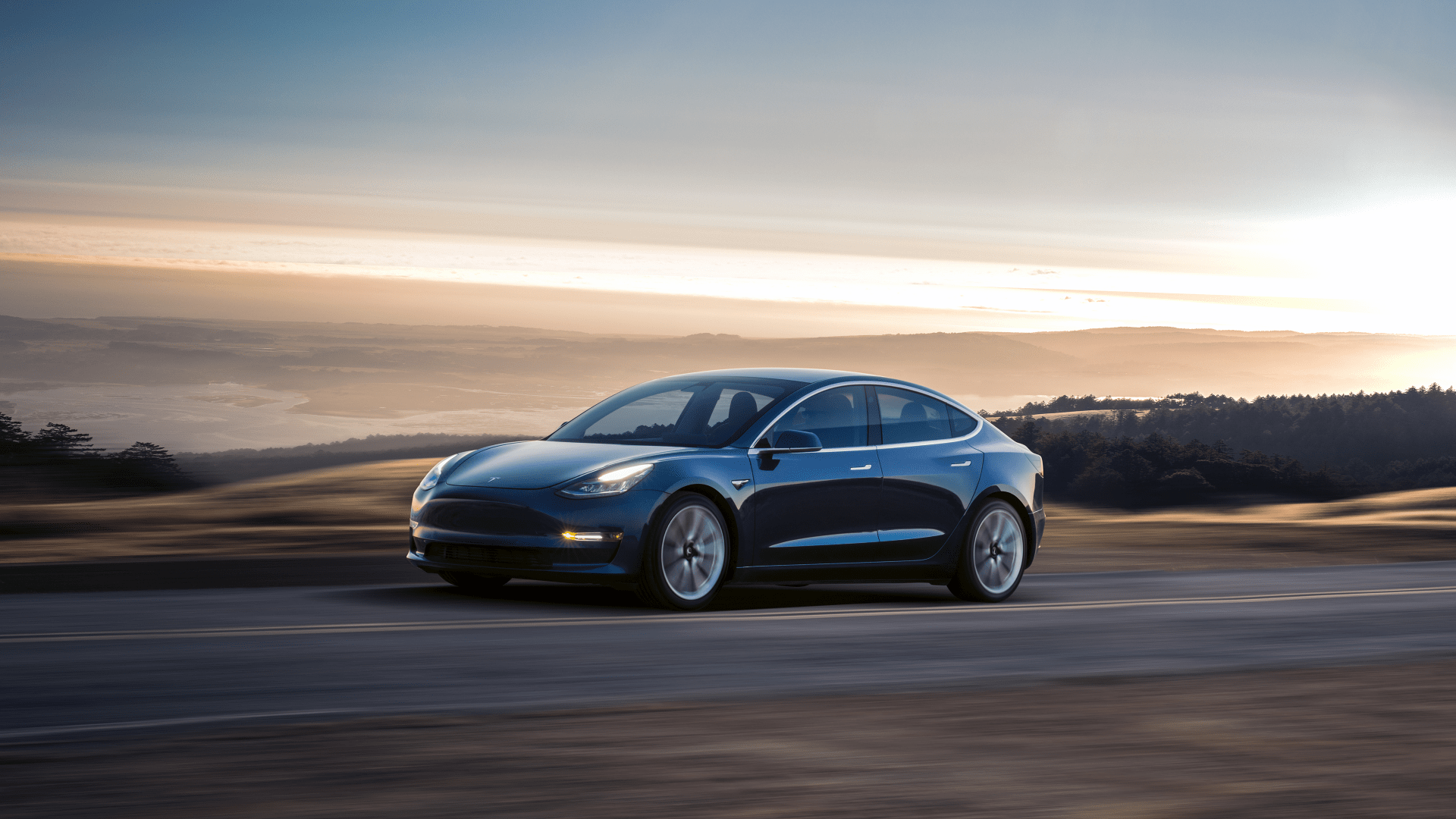

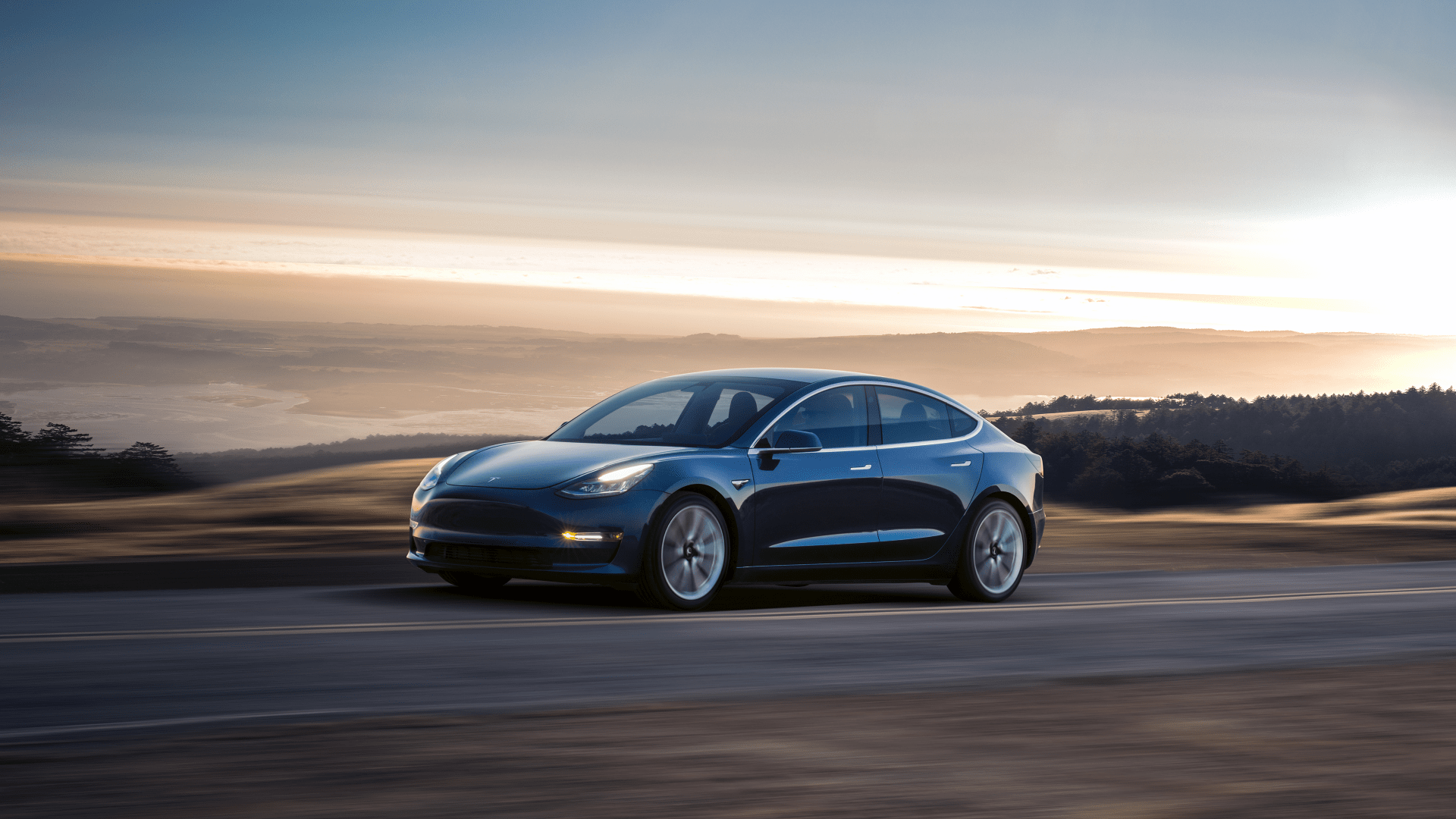

At the CanSecWest security conference, and its Pwn2Own competition, a number of the conference attendee’s eyes were on a gleaming Tesla Model 3. Waiting to be hacked, the car sat stationary in the conference hall. The Tesla’s presence represented the first time the competition held an automotive category. In the end, just a single team of white-hat security researchers entered and proved hacking a Tesla was entirely possible.

Designed to exploit the car in a limited capacity, Amat Cama and Richard Zhu—known as Team Fluoroacetate—utilized a hole in Tesla’s infotainment software and displayed a message across the Model 3’s web browser. According to the team, the researchers exploited a “just-in-time” bug in the infotainment’s rendering element. As a reward, Cama and Zhu won $35,000 and the actual Tesla Model 3 the team hacked. Cama and Zhu went onto win an additional $340,000 by finding vulnerabilities in systems built by Safari, Oracle, VMware Workstation, Microsoft Edge, and Firefox. Tesla, however, had a number of other uncollected prizes available to the researchers attending the conference.

As a means of finding vulnerabilities, companies often offer quite lucrative “bug-bounties” to white-hat hackers and security researchers who find such issues. The practice has become quite common and helps ensure that hackers and researchers have the incentive to offer up their exploits to affected companies. Before the conference, Tesla had announced that it would offer bug-bounties on the infotainment, which Cama and Zhu exploited, as well as hacks for the Model 3’s modem, audio tuner, Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, key fob, phone application, and autopilot with the specific focus on the autopilot and security system’s entrance portals—a bounty of $250,000 was offered on the latter potential exploit.

As electrification endeavors intensify, automotive manufacturers are spending more research and engineering resources—both time and money—focused on the function and exploitability of a car’s electronics. Nearly every system is now controlled by the car’s ECU, and with Over-The-Air updates becoming more routine—as well as in-car phone-based applications, Wi-Fi, LTE services, non-native applications, and out-sourced operating systems—these systems have become a hotbed of potentially exploitable vulnerabilities. With that in mind, security conferences and so-called “Hackathons,” like the Pwn2Own competition, will need to rapidly become required stops for automotive manufacturers and their engineers. Automotive bug-bounties will also grow to be more common; General Motors and Fiat Chrysler both already have operational bug-bounty programs.

The average car is already becoming increasingly complex in its usage of electrical and computer-controlled systems; not to mention the ever-thrumming drumbeat signaling the advancing autonomous age. Tesla’s bug-bounty program should be commended as the company took the necessary steps toward better security. However, unless real development and engineering occur before the car reaches the public, vulnerabilities like the one that Cama and Zhu exploited could lead to more tangible public safety threats. Every manufacturer needs to do a better job at making network and in-car-electronic security a priority.