When I bought my first car, a Toyota MR2, I did so without even considering the United States’ mid-engined alternative, the Pontiac Fiero. On account of its rep for catching fire, being tricky to drive, and popularity with kit car goobers, it’s more often than not the butt of a joke. Plus, it was an ’80s General Motors product, which was about as far as you could get in every way from the sport compacts of Japan’s golden age—cars like my MR2. As I’ve grown older, though, and my horizons broader, I’ve found myself wondering: Was I missing out on something? In spite of the Fiero’s reputation, was it actually good and a worthy alternative to the more esteemed MR2?

I got my answer from a couple of hours’ track time in what’s probably one of the best Fieros out there: The venerable number 90 of Salty Thunder Racing, a 24 Hours of Lemons team. While the series may be known for its $500 race cars, this two-time class winner is no hunk of junk. It’s about as good an example of a Fiero as they come, and it convinced me that Pontiac’s mid-engined sports car is an overlooked classic.

1985 Pontiac Fiero Race Car Review Specs

- Purchase price: $500

- Powertrain: 2.8-liter V6 | 4-speed manual | rear-wheel drive

- Horsepower: 200 (approximate)

- Curb weight: 2,480 pounds

- Provenance: Two Class B wins in the 24 Hours of Lemons

- Quick take: Mid-engined, analog, and often scoffed at, the Pontiac Fiero is an under-appreciated bargain by modern sports car standards.

Another GM Icarus

GM’s Chevy Corvette protectionism has claimed many victims over the years, and the Pontiac Fiero was one of them. After a rough few years of unrealized potential (during which it developed its reputation for catching fire), the Fiero finally blossomed in 1988 with a comprehensive suspension overhaul. The time was ripe, then, for GM to kill the car, as it so often does with its best creations, leaving the Fiero’s true upper potential unexplored. As a result, the mainstream remembers the often Fauxrrari-fied Fiero as a car for people who couldn’t get what they really wanted—a Countach, Corvette, or even an MR2.

But even imperfect cars have their diehards, one of them being the head honcho of Salty Thunder Racing, Jeff Hanka. He bought this Fiero several years ago for just $500 with the intent of turning it into a Lemons car. Over several years of trial and error, he has gradually ironed out the Fiero’s flaws and improved its performance, dipping into OEM parts bins wherever possible.

Yack 2.8

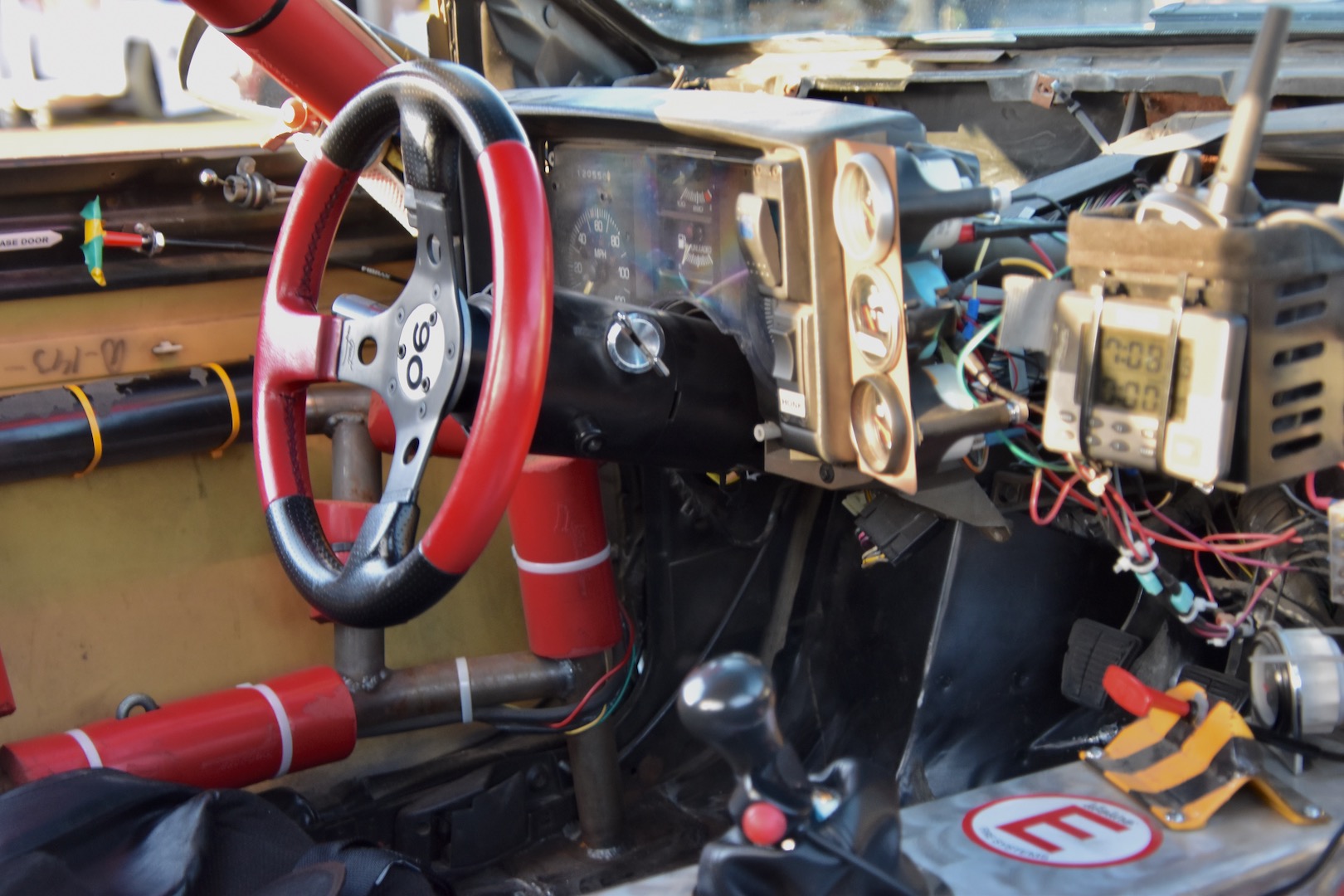

The result is the spec of Fiero I raced, which he calls Yack 2.8. It’s only a coincidence that its build number matches its displacement of 2.8 liters. Its V6 is brought to life by a hot cam, ported heads, a bored-out throttle body and intake manifold, and short-tube headers. It only makes an estimated 200 horsepower, but that’s plenty competitive in Lemons, and as any spec racer could tell you, more than enough to separate the wheat from the chaff.

That power travels through a four-speed manual transaxle to heavier-duty hubs from the front axle of a GM J-body (think a Chevy Cavalier) and widened 255-section tires, pressed down by a spoiler from a Dodge Shadow. It needs that kind of rubber because of its tail-heavy 43-57 weight distribution, which is part of why the Fiero was known for pirouetting when drivers mishandled it. That was also because the pre-’88s lacked rear sway bars, which Hanka addressed by moving the stock 23-millimeter bar to the rear, and upgrading the front to 25 mm. Up there are also an IMSA-style chin spoiler and Embrace Racing flush HID headlights, improving aero, and an aluminum radiator for better cooling and reduced weight.

The Fiero was never a heavy car to begin with, and this one’s particularly svelte at 2,480 pounds with fluids. It is weight carried well by a combination of Eibach springs, KYB shocks, and poly suspension bushings. “Five hundred dollars, my ass,” the joke goes in the Lemons community, as if anyone’s car has ever cost that little—the reality is everyone’s thousands deep in safety gear alone. Because brakes qualify as safety equipment, they’re budget-exempt, though this Fiero’s aren’t anything exotic. All four corners just have GM Metric 2.5-inch calipers (used in multiple grassroots spec series) and rotors from the rear of a Chrysler LeBaron.

Green Flag

I got to see what this loyally prepared Fiero could do at Colorado’s High Plains Raceway, the site of one of the best Lemons races in the country. It’s also a track where I’ve also driven the Fiero’s direct competitor, the first-gen MR2.

From the sweeping right-hand pit exit, it was already clear the two cars didn’t handle alike. Bone-stock, MR2s are a strange blend of by-the-stern handling and blunted front ends to reduce the risk of Initial D wannabes spinning into trees. This Fiero, on the other hand, was surprisingly on-the-nose; it felt like it was rotating on a point just ahead of the shifter. Having this point of reference made it easy to begin exploring the bounds of the traction circle, all while keeping Hanka’s advice in mind: Don’t push it too hard, and it won’t bite.

It was an easy rule to follow, as over my first one-hour stint I learned that as long as I took care of the Fiero’s front end, everything else would be okay. My duty was to pay close attention to the front tires’ load through the small-diameter steering wheel, which had the effect of accelerating the rack and amplifying its feedback. Having just 225s up front, it didn’t take a feat of strength to hold it through the sweepers, where the car was glad to tell me when my steering input approached too much.

Accordingly, the first time I truly exceeded the front end’s limits was not in a corner, but under heavy braking on a straight. The judder of the race pads against the rotors made it difficult to tell when I was close to locking the brakes, and when I did, they did so on both axles, causing an alarming rear-end twitch. A subsequent lockup a few laps later produced the same result to a scarier degree: This was the Fiero’s way of telling me it wouldn’t tolerate being grabbed by the scruff of the neck.

I’ll admit, I wasn’t as confident in this Fiero’s upgraded brakes as I was in my MR2’s, which I could hit later in spite of its tendency to lock the front wheels. Of course, I have much more experience in that car, so the weak point may not be the car, but rather myself. It may also have something to do with the Fiero’s corner entry speed, which was higher than my MR2’s on account of its punchier drivetrain.

Those 200 hp have sailed this Fiero past me more times than I can count, and reasonable torque meant that I could take the entire track in third. But I preferred heel-toeing into second for slower corners: a graceful motion into hairpins, but clumsier in mid-speed corners, where my downshifts were jerkier. The inconsistency suggests that—again—this is a me problem and not one with the Fiero’s four-speed manual, whose short shifts made it a cinch to find gears. By contrast, MR2s aren’t known for having good shifters.

Only a few times did I bother shifting into fourth on the back straight, having been told I didn’t need to. I’m not so sure about that; while shifting at 6,000 seemed to be the rule, I don’t think the engine made much power past 5,500. The V6’s homely sound didn’t tempt me to hold on to revs, either, but it was a noise I grew fond of regardless as the laps and successful passes we racked up.

As they did, I gradually grew more comfortable taking corners faster, braking harder and later, even testing out trail braking in a way I never have in an MR2. I eventually got familiar enough that I could make the rear end waggle into slower corners, tightening my line. A sharper driver than I could do it more consistently, but I didn’t want to risk getting that wrong when Salty Thunder was challenging for the class lead. Besides, both the car and I were happy to take things at eight-tenths, knowing that nine were for better drivers, and that 10 were downright perilous. Even at that pace, I set a personal lap record of 2:25, a good four seconds quicker than I’ve ever lapped in my team’s MR2.

Don’t Fiero the Reaper

I know the Fiero I drove isn’t representative of every one out there. Most of them aren’t rolling around on race-proven suspension with almost 50 percent more horsepower than they made stock. Most are gutless, Iron Duke-powered dogs, and far too many have embarrassing Ferrari 308 body kits on them. It doesn’t matter. We don’t romanticize old cars with any consistency, and we’re glad to overlook the MR2’s numerous flaws because … Japan.

But the fact is that almost every car has more performance to bring out, like Hanka has with his Fiero, resulting in an analog, mid-engined driving experience more rewarding than many modern performance cars. My opinion of the Pontiac Fiero—as someone who has raced both in and against it in its direct rival—is that it’s a good, under-appreciated classic sports car.

Knowing that, I now realize how idiotic I was to have argued with a Fiero owner over whose car was better in the comments section of an old /DRIVE video. The dispute missed the point: While we chose different cars, we should have been united in our appreciation of affordable mid-engined machinery. The world could only be a better place if both our cars are good, and they are.

Got a tip or question for the author? You can reach them here: james@thedrive.com