We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn more ›

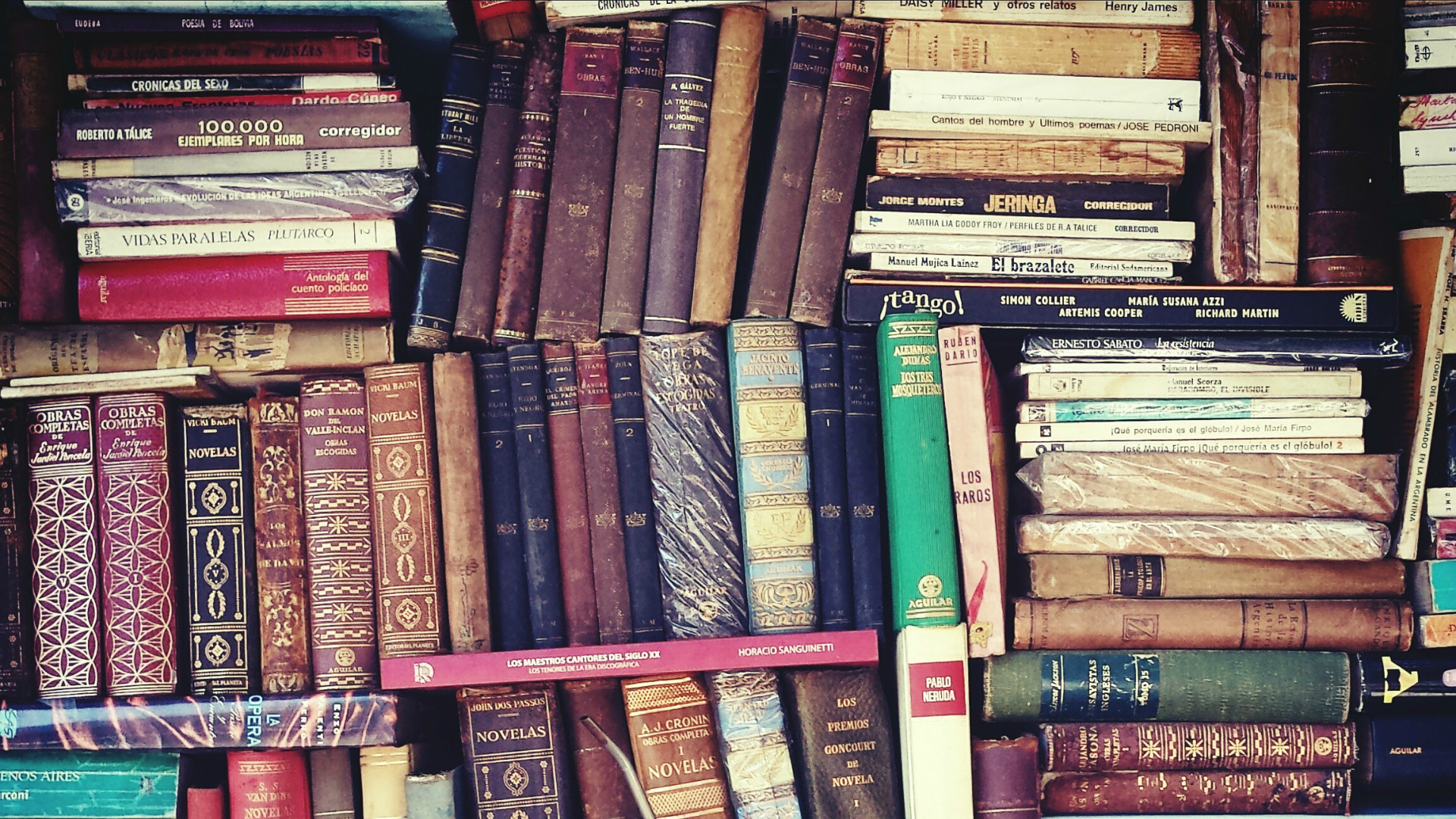

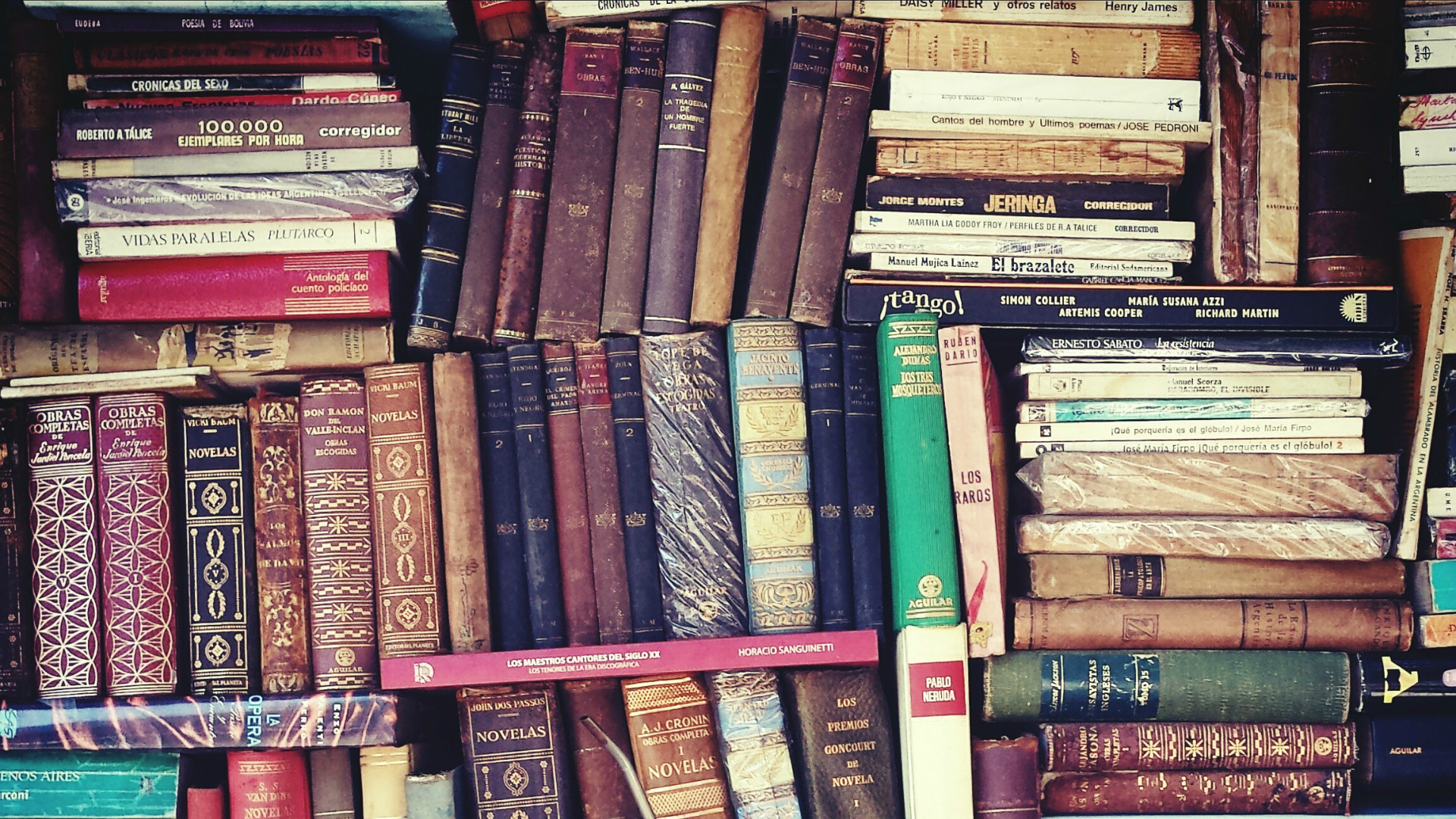

Before it ran off the rails, before the licensed sex toys and gas station keychains and mail-order VHS tapes, Playboy was a bastion of great journalism and incredible writing. Vonnegut, Updike, Nabokov, Mailer—they all contributed to Playboy, and so did Ken Purdy, the preeminent automotive writer of his era. The magazine’s zenith came in the mid-seventies, when circulation crested 5.5 million, and Hugh Hefner published The Twentieth Anniversary Playboy Reader. Last week, I found an old copy buried in the cellar of a used bookstore, beaten to hell and priced at $9. I bought it, and haven’t been able to stop reading since.

Twentieth Anniversary is a 788-page cinder block of an anthology. Stripped of the centerfolds, varnished down to ink on paper, adjectives and verbs, it absolutely shines. William F. Buckley on Soviet Russia, John McPhee on Wimbledon, fiction from Joyce Carol Oates that’ll turn you inside out—it’s all here. But nothing beats “A Nodding Acquaintance With Death,” the landmark profile of Stirling Moss written by Purdy for the September 1962 issue.

It takes place mostly in a hospital, where Moss is recovering from his horrific crash at Goodwood. He’s bloody and brain damaged, arrogant and fantastic and introspective. He speaks Italian in his sleep, flirting with women while dreaming about Monza. He says that he could run a four-minute mile or walk on water if he tried hard enough. He talks about Jack Brabham, Enzo Ferrari, Graham Hill, about car control and crashing. The story is poignant as it is funny and romantic, Grand Prix racing at its best and also its most gruesome, when the mortality rate for drivers was 25 percent. Here’s a sample:

The full terror and the full reward of this incredible game are given only to those who bring the car talent honed by obsessive practice into great skill, a fiercely competitive will and high intelligence, with the flagellating sensitivity that so often accompanies it. In these men a terrible and profound change takes place: The game becomes life. They understand what Karl Wallenda meant when he said, going back up on the high wire after the terrible fall in Detroit that killed two of his troupe and left another a paraplegic, “To be on the wire is life; the rest is waiting.”

…Once a man has gone over, the terror of his nights will be not mortal death, which he will have seen many time and which, like a soldier, he believes is most likely to come on the man next to him and the risk of which is, in any case, the price of the ticket to the game, but real death—final deprivation of the right to get back on the wire. Then, like Moss, he’ll do anything to get back. In the hospital, Moss would accept any pain, any kind of treatment, anything at all that he could believe would shorten, if only by very little, his path back to the race car, never mind the fact that it took a crew of mechanics 30 minutes with hacksaws and metal shears to cut the last one apart enough to make it let go of him.

Hooked? You should be. Take a spin through eBay or the local used bookstore, and find a copy of The Twentieth Anniversary Playboy Reader of your own. The 33 pages of Ken Purdy on Stirling Moss are required reading for anybody who loves cars. The other 755 are just a bonus.