There is a simple explanation for the latest Tesla Autopilot crash. It is not as simple as blaming the “driver,” although that’s where legal responsibility falls. It’s also not as simple as blaming Tesla Autopilot, which isn’t a technology but a brand comprised of an evolving set of functionalities. It is the same explanation as every other crash attributed to Tesla Autopilot that has ever occurred, and every crash that will occur in the future as long Tesla or anyone else offers such systems.

The explanation is that “series” automated driving systems—of which Tesla Autopilot is one of only two good ones—cannot eliminate these types of crashes, even if they work perfectly.

Why? Because they’re not designed to.

Series automation temporarily substitutes for human input rather than augments it. As I stated a year ago, the more such systems substitute for human input, the more human skills erode, and the more frequently a ‘failure’ and/or crash is attributed to the technology rather than human ignorance of it. Combine the toxic marriage of human ignorance and skill degradation with an increasing number of such systems on the road, and the number of crashes caused by this interplay is likely to remain constant—or even rise—even if their crash rate declines.

These persistent crashes define the half life of danger: unless and until a universally autonomous/self-driving car arrives, which by definition requires no human input anywhere, anytime, no improvements in automated driving can totally remove the risk of a crash.

Between now and universal autonomy/self-driving, however, there is an alternative to the series systems we currently see on the road. It’s called parallel automation, and it has a well established history in aviation. The most advanced commercial and military aircraft combine series and parallel automation, and in concert with professional training have made our skies orders of magnitude safer than our roads.

There is no Tesla Autopilot problem—at least, there is no problem unique to Tesla Autopilot. There is, however, a grave conceptual problem inherent to all series automation, magnified by media scrutiny of Tesla Autopilot at the expense of deeper, broader comprehension of automation, and masked by misunderstanding that starts with language.

Automation ≠ Autonomy

Critics love to cite Musk’s co-opting of “autopilot” (as in, the autopilot in an aircraft) for the Tesla Autopilot branding as misleading, but that merely conflates one misunderstanding with another. Aviation autopilots come in many forms, but none of them make aircraft autonomous. They’re automated. Aviation autopilots don’t make decisions. They execute them by automating repetitive tasks, and they still don’t automate them all—at least in practice. Human pilots remain “in the loop” due to tacit cultural and deliberate technical constraints. Why? To make high-level decisions, and to manage system failures and edge cases. Sully Sullenberger‘s Miracle on the Hudson is a perfect example of how human pilots manage edge cases. The crew of Air France 447 is a perfect example of how human pilots can fail to manage edge cases.

Human failures don’t make the case for more automation, they make the case for better automation.

Anyone who believes aviation autopilots or Tesla Autopilot are autonomous hasn’t looked inside an aircraft cockpit and asked themselves why there are seats.

Does this absolve Tesla of responsibility for using “Autopilot” for their branding of a car-based automation suite? Legally yes, but effectively no. Yes, in the sense that Tesla Autopilot does automate many repetitive driving tasks, and includes a system to warn users of when that automation may cease. No, in the sense that some people ignore warnings, conflate automation with autonomy, overtrust systems they don’t understand, and often lack the skills to safely retake control even when they do.

Automation and the Problem of Understanding

Automation is only as good or safe as our understanding of it, and we have entered the uncanny valley where understanding it in cars requires a level of driver training equivalent to that of pilots.

What is the solution? It could be driver training via gamification of Autopilot (and similar systems), but no car manufacturer wants to add potential liability. It is both cheaper and easier to wall off responsibility behind warning systems and legalese, but these are passive defenses rather than active solutions.

As long as humans are in the loop, everything must be done to educate them not only to what automation can do, but what it can’t. Everything must be done to prevent users from abusing it, even due to their ignorance. If this isn’t done by government mandate, auto makers should do it by moral imperative.

A system that works as designed does not equate with a perfect system. If perfection is “the action or process of improving something until it is faultless, or as faultless as possible,” then it must include a good faith effort to inform users of both its limitations and purpose.

What is the purpose of Tesla Autopilot and its only functionally equivalent peer, Cadillac SuperCruise? It’s not safety, it’s convenience. The foundational safety functionality of both systems—radar-based braking—is the core of the Automatic Emergency Braking (AEB) which is active under human control. All Autopilot and SuperCruise equipped vehicles offer radar-based adaptive cruise control which can maintain both speed and distance to a car in front. That any cruise control is safer with radar than without is obvious, but that additional safety is available without activation of the functionality that enables Autopilot and SuperCruise, which is active lane keeping, or what Tesla calls Autosteer.

I have greatly enjoyed using both Autopilot and SuperCruise, but I’m unaware of any study proving that active lane keeping enhances safety. The NHTSA claim that Tesla Autopilot reduces crashes by 40%? They remain unable to explain it, nor has it been verified by any third party I’m aware of. There is every reason to believe that Autopilot safety claims are largely—if not entirely—based on the effectiveness of radar-based braking within TACC and AEB, and that attributing any additional safety to the use of Autopilot/Autosteer may in fact diminish safety, at least in series type-systems.

Let’s find out why.

How Safe Can Series Automation Be?

As long as Tesla Autopilot and Cadillac SuperCruise require the “driver” to take over anytime while allowing them to remove their eyes from the road and/or take their hands off the steering wheel, an element of danger will remain. Automated braking and steering may improve, but the half-life of danger will always depend on how aggressively the systems compel driver awareness and reduce human response time to takeover warnings.

As long as there’s wiggle room, humans will exploit it.

Given the complex nature of traffic, every millisecond counts. If driver awareness is linked to whether one’s eyes are on or off the road, and response time is linked to whether one’s hands are on the wheel, a conceptual safety matrix looks like this:

Why is eyes on/hands off safer than eyes off/hands on? Because you can’t steer around what you can’t see, but you can brake for what you do.

Now let’s add the element of eyes off/hands off time intervals:

The shorter the eyes off interval the better, and this can only be reduced via a camera-based driver monitoring system. The shorter the hands off interval the better, and this can only be accomplished by a steering wheel sensor.

What happens when you put the two best series automated driving systems on the chart? Prepare for fireworks:

Why does SuperCruise land where it does? It’s got an infrared camera pointed at the driver’s face. You can look away, turn your head or lean over, but the system warnings will light up within seconds. Take too long and SuperCruise will shut off. It’s very hard to cheat, and I tried. Also, it has a big visual state of engagement light perfectly placed on top of the steering wheel. Is SuperCruise on or off? There’s never any doubt. Why isn’t SuperCruise further to the right? Audible warnings aren’t as good as visual, and because of its liberal hands off policy; you’re going to need that extra second to get your hands back on the wheel.

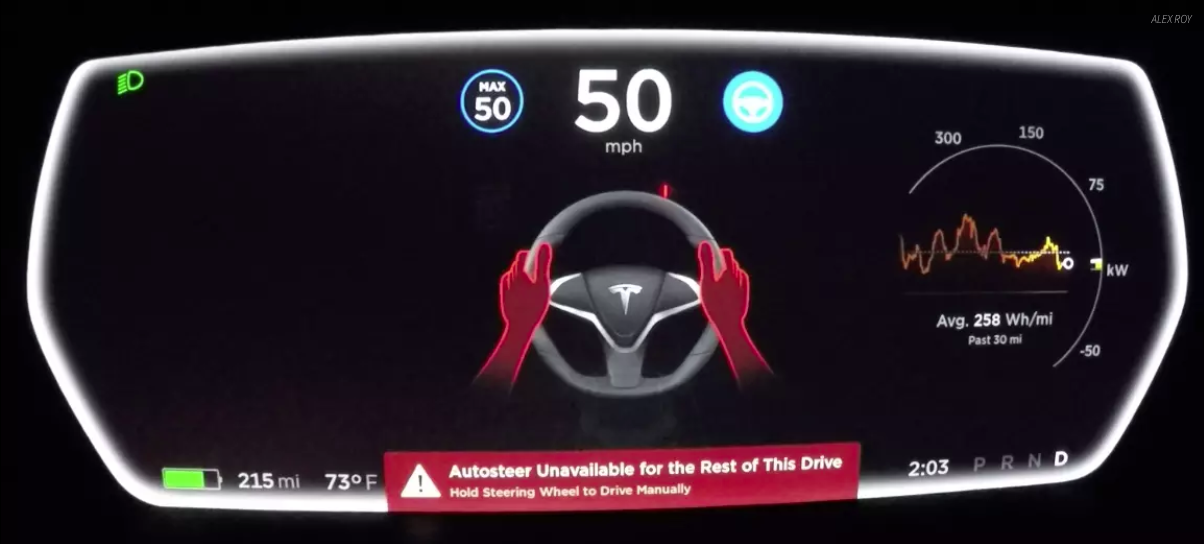

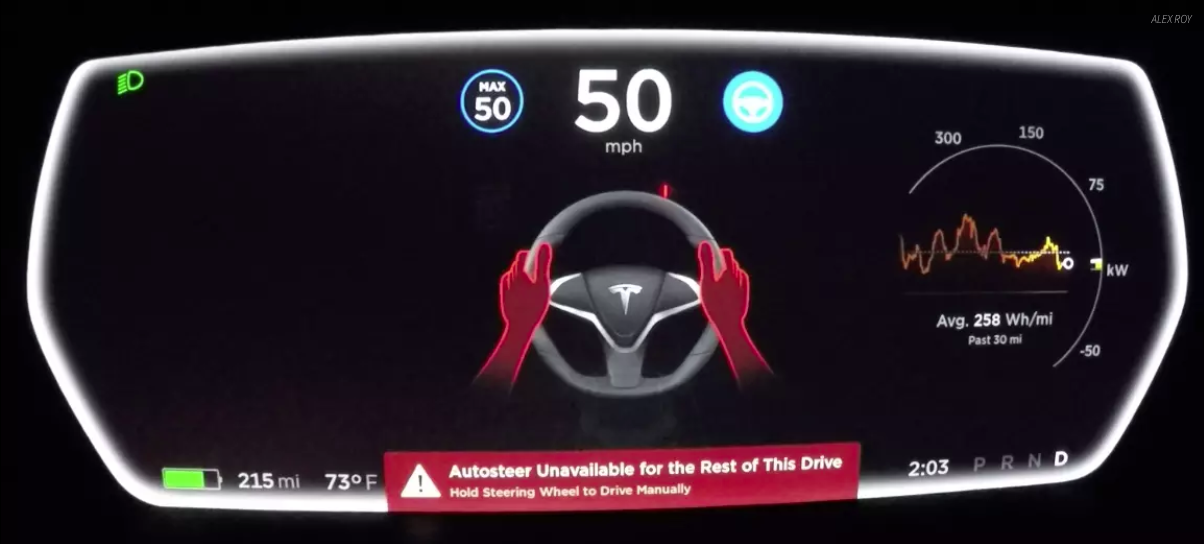

What about Tesla Autopilot? It’s complicated. To their credit, Tesla has consistently improved Autopilot’s safety since its release in October of 2015. From the 1st gen Autopilot 7 & 8 though the current 2nd generation, hands off intervals have gotten shorter and visual warnings have gotten clearer. Unfortunately, audible warnings remain only adequate and Tesla still doesn’t offer an active driver monitoring system. Unless the tiny camera above the Model 3’s rear-view mirror wakes up and turns out to have been designed for this purpose, Tesla’s current safety hardware is behind Cadillac’s. How about those S/X models? No camera. Tough luck.

Furthermore, Tesla’s hands off intervals are measured by a steering wheel torque sensor rather than capacitive touch. It’s not that hard to cheat a torque sensor with one or more water bottles. It’s very hard to cheat a capacitive sensor, and any car with heated steering is a few dollars away from enabling capacitive touch functionality. There’s only one reason not to offer capacitive touch, and that’s cost.

What is the point of series automation if the convenience of eyes off/hands off must be designed out in order to reduce the half-life of danger? None. At current levels of technology, companies are selling convenience at the expense of safety. I love both Autopilot and SuperCruise, but I don’t reduce my vigilance when using them. I increase it. Not because they force me to, but because I know that if I don’t, I could be the next Josh Brown or Walter Huang.

What is the solution to the limitations inherent to Autopilot and SuperCruise?

Series Vs. Parallel Automation

The alternative to series automation is a “parallel” or what Toyota Research Institute (TRI) call a “Guardian” system. Parallel systems have barely entered the thinking of an automotive sector trapped within the prison of the SAE automation level definitions. Parallel systems are the opposite of series; they restore the relationship of the driver to driving by forcing hand/eye engagement and limiting the user’s ability to make mistakes. If current series systems are like Wall-E chairs that work some of the time, future parallel systems put us all in Iron Man suits.

#WouldYouLikeToKnowMore? Here you go.

What is the perfect car of the future, after all? The perfect car of the future is self-driving when we allow it, and—if and when we choose to take the wheel—won’t let us harm anyone else. That perfect car requires two things we don’t yet have on the ground: universal autonomy/self-driving, and parallel automation. Broadly, it would include an Airbus-type system: series automation (autopilot) and parallel automation (flight envelope protections). An Airbus won’t let you exceed the limits of the airframe. Why should a car let you steer into a wall?

What about autonomy? Safety requires clarity. If a car requires a human operator or external control anywhere, it’s not autonomous, it’s automated. Until that arrives, let’s call things what they are, and focus on problems we can solve.

How can we seriously attack the half-life of danger until parallel systems and universal autonomy/self-driving arrive? I see at least three options at this time, although there may be others:

- Ban all active lane keeping, and therefore Autopilot, SuperCruise and any other emergent systems. No one will like this except regulators and Luddites.

- Mandate geofencing of all series automation to low density, separated highways a la SuperCruise. Tesla could easily do this via wireless update, but who is to say where to place those geofences? Even the excellent SuperCruise works some places it shouldn’t.

- Mandate Driver Monitoring Systems, to include both camera and capacitive touch, therefore banning Autopilot until hardware improvements arrive. Tesla and their investors and owners will hate this. Cadillac? I’m not sure they’ve sold enough SuperCruise equipped cars to care.

Or we can do nothing and suffer through the same clickbait and hand-wringing over and over until the next crash. And the next one. I’d rather not.

Alex Roy is the founder of the Human Driving Association, Editor at The Drive, Host of The Autonocast, co-host of /DRIVE on NBC Sports and author of The Driver, and has set numerous endurance driving records, including the infamous Cannonball Run record. You can follow him on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.