I’ve heard of this Robby guy. Cool customer on the racetrack, precise and unblinking, with talent and training to spare. Throw in factory support from Audi, with a seemingly unlimited budget, and I’m feeling the pressure here at FAST Parcmotor Castelloli, a hilly, 2.6-mile dustbowl of a race circuit near Barcelona. Robby is getting inside my head, and I can’t get into his. Well, at least without a laptop.

Robby’s an autonomous car, a 560-horsepower RS7 sedan. Where other self-driving Audis have been negotiating everyday traffic from Shanghai to San Francisco, this one’s designed to kick ass and push the dynamic limits on track.

Today, Robby has set a 2m, 9s lap time Parcmotor Castelloli, which Audi assures me will take effort to beat. Robby’s big brother, Bobby, after all, was saddled with 882 extra pounds—bulkier computer controls, plus a back seat—when it set the speed record for a piloted car, 149 mph, at the Hockenheimring in Germany. It did a 2:01 at Sonoma Raceway in July, beating many track-experienced drivers in the process. And this digital scion has a tradition to keep, a family album that includes Shelley, the autonomous Audi TT that drifted its way up Pikes Peak. (Please, Audi, name the next self-driving racecar Ricky Bobby. I beg you.)

I spot Robby in the pits, wrapped in a tidy black-and-white livery. Under the hood is a 4-liter twin-turbo V8, with a lightweight exhaust system that sends rasp echoing off barren ravine walls. I gotta admit, he sounds amazing. I take to calling it Robby the Robot, after the seven-foot cyborg from the 1956 classic Forbidden Planet. I can only imagine what sci-fi fans in that Jet Age—a skies-the-limit era of tailfinned, Virgil Exner specials—would make of the Audi.

Autonomous tech is advancing at a breakneck pace. Google and Apple see it as their entryway into making cars, and a potential advantage over legacy automakers. But the established brands aren’t ceding the battle. Audi’s piloted A7 has topped 130 mph on the German Autobahn; the company’s all-new Q7 crossover, which we’ll drive in a few weeks, can manage its own steering, throttle and brakes in stop-and-go highway situations. In 2017, an all-new A8 flagship sedan takes things to the next level, with so-called “sensor fusion” creating an integrated 360-degree picture of the road. Radar scans the road ahead, with 3D cameras detecting everything from lane markings to vehicles and pedestrians. A laser diode pulses nearly 100,000 times per second, creating detailed scans of objects nearly a football field away. Forget the Jet Age; kids who grew up on Star Wars can barely believe this stuff.

Dr. Miklós Kiss, Audi’s head of predevelopment for driver assistance systems, walks us through it. Where Bobby’s hatch is crammed with gear, Robby’s has room to spare. It’s only 155 pounds heavier than a stock RS7. There’s a single Microautobox brain and power supply, and two other small computers. Incredibly, the differential GPS unit can fix Robby’s position within two centimeters, using redundant cameras to triangulate and confirm location. That’s vastly superior to today’s best production-car GPS units, which can locate to within roughly 1.5 meters; keeping a car in its lane on public roads will require zeroing in to around 50 centimeters.

The gadgetry is impressive. But sliding into Robby’s passenger seat, I’m more nervous than I am riding shotgun with a professional racer. Engineers manually drove the RS7 to measure the track’s left- and right-hand barriers and geo-fence a no-go zone. Still, I’m relieved to find an Audi engineer in the driver’s seat, holding a plunger attached to a cord that’s like a suicide grenade in reverse: Let go of the button, and the Audi will come to a safe halt on track. Theoretically.

With the wave of a checkered flag, we’re off. The RS7 howls down the front straight, then dives into a right-hander. Its steering wheel twirls and unwinds as it rolls back into throttle. Robby turns out to be a smoothie, a Skip Barber-instructor type: Fast and flowing, keeping the car balanced, easy inputs. I notice that the brake and throttle pedals don’t actually move, controlled by an unseen electronic hand. The ghosts are fully in charge of the machine.

Robby’s consistent, too. The racing line varies by only a few centimeters, lap after lap. It cranks off times varying by less than 0.3 seconds: From a best of 2:09.2 to 209.5. Though locked onto GPS coordinates, the autonomous RS7 also reacts in real time to conditions, such as tire wear or a slippery track, dialing back power or adjusting steering angle. Oversteer, we learn, is much easier to digitally correct than understeer.

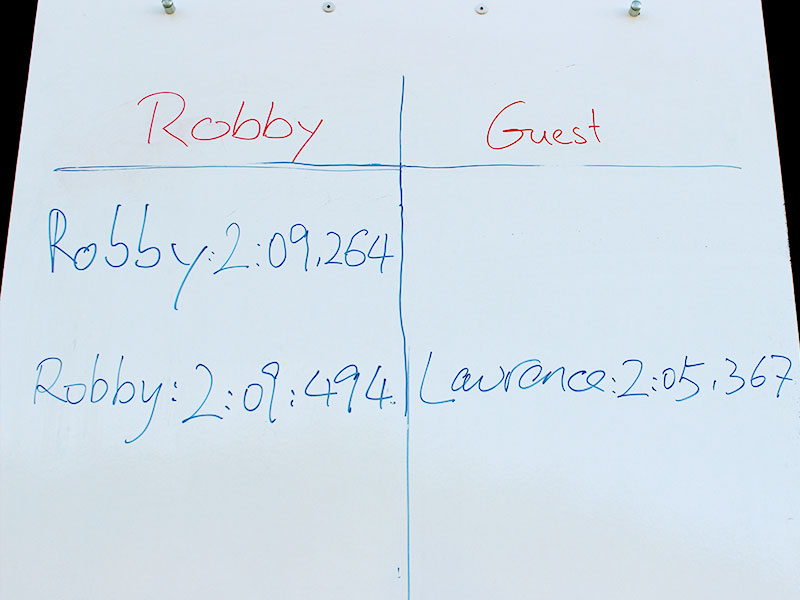

My turn. I grab a helmet and hop aboard a stock RS7. An engineer scribbles Robby’s latest lap time onto a whiteboard. The gauntlet is thrown. And, suddenly, I’m Bobby Fischer and John Henry, a fallible human fighting in the name of his increasingly obsolescent species. Slow in, fast out, eyes up, I remind myself. I may not have 360-degree vision, but I’m praying I’ve got enough senses and skills to avoid being embarrassed.

After one reconnaissance lap, I turn it loose. One lap. One shot.

What seems like moments later, I’m rolling back into the pits. My inner race coach, the naysayer and critic, tells me it wasn’t my best. But there’s a smattering of polite applause. Applause?

It’s official: My time of 2:05.4 is nearly four seconds quicker than Robby’s. Even with a few hundred laps under its belt in recent weeks, the automated RS7’s best here is more than two seconds behind my first-ever trip around Castelloli. On the racetrack, that might as well be an eternity. Take that, you unholy Terminator.

There are, of course, concessions. Where I was trying to beat Robby, he was emotionally uninvolved; the word “race,” and all its competitive baggage, is not in his vocabulary. Where I howled the Pirelli P Zero tires, adjusted my line and pushed the limits, Robby followed his programming to run fast, safe and endlessly repeatable laps. A few tweaks of the algorithms, a few more generations, and the Robbies of the world will be chip-enabled Schumachers, programmed to chase down overmatched humans and leave us choking on silicon dust. What’s to stop them?

No form of mobility has ever died out, whether it’s horses, sailboats or the racing thereof. But, eventually, when an entry-level Honda comes standard with the skills of a professional racer, it might be hard to convince regulators and lawmakers that people—distractible, unpredictable, some drunk or otherwise lethal—deserve a place behind the wheel. When deaths and injuries plummet, and robot cars lead parades in their own honor, people will shake their heads and recall the days of mortal pilots and their endless, tragic fuck-ups.

I hope I don’t live to see a day when the keys are pried from our hands. But some part of me, surely the overprotective one, wishes it for my daughter. Because, love for the machine be damned, I’m only human.