We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn more ›

This is from an interview I did with consumer advocate Ralph Nader that appeared in Car and Driver magazine in September of 2009:

C/D: You got plenty of attention in the enthusiast media, like Car and Driver.

RN: Oh, yeah.

C/D: Did you ever take it personally?

RN: No, because I knew they would look ridiculous in the light of history. If you read some of the stuff in Car and Driver that was hurled at me in the 1960s and early ’70s—I mean it was—what’s the name of that guy who worked there? That Fireball guy?

C/D: Brock Yates?

RN: Yeah, Brock Yates! I mean, he looks like an ass now! Some of the commentary was so absurd as to invite permanent satire. Whoever writes the history of this will, I’m sure, be able to comment on how the automotive magazines should have been in the vanguard, right? Well, they were basically defending a colossal technological stagnation subordinated by a colossally pornographic styling mania. And all they were really interested in was power and acceleration!

Hmm. “Pornographic styling mania,” and “power and acceleration.” You nailed it, Nader.

I met Brock Yates 31 years ago. Eventually, when I became executive editor and Car and Driver, Brock worked for me. Technically. He worked for me the way LeBron James “works” for Cleveland Cavaliers coach David Blatt. Brock was the star, the franchise player, and some people resented that, but I never did: Had I not met Brock Yates, I never would have had a career, thin as it might be, in automotive journalism.

Brock, of course, died Wednesday at 82, but his mind went long before that, courtesy of Alzheimers. My mother died from it, too. Toward the end, when he couldn’t remember names, everybody was “Pal,” or “Bud,” or “Teammate.” You could see his mind spinning the combination of the lock, but it wouldn’t open. And then – well, he deserved better. So did his family. So did all of us, deprived of what could have been another couple of books, or a hundred columns.

I have a lot of Yates stories, but the first one might be my favorite.

Brock stopped by the Dallas Times Herald in 1985, where I wrote a weekly test drive column in addition to my other duties, which was mostly doing endless, tedious investigative stories. Then, when you got your journalism degree, that’s what you were supposed to do: I hit the University of Missouri-Columbia journalism school in the churning aftermath of Watergate and Woodward and Bernstein as a junior, older than the other students after staying out of college for a year, when I rode motorcycles and waited to see if my number would come up for the Vietnam draft. I was 1-A. But it didn’t. So I stumbled through junior college, and ended up at Missouri not because it was the world’s oldest journalism school (it is), but because my girlfriend and I had broken up, and in a Grand Gesture, I got in my car and drove 425 miles to apply to Missouri. No one was more surprised than me when I was accepted. The admissions guy, Mr. Lister, said something about wanting at least one student that wasn’t a kennel-bred hothouse flower.

So, next semester, I showed up, the only J-school student driving a 1973 Plymouth Road Runner with a 400 cubic-inch engine, Thermoquad four-barrel with secondaries so big you could have tossed a silver dollar down them, and a Hurst pistol-grip shifter, towing a U-Haul with a yellow pearl Suzuki Titan with expansion chambers inside. I worked at night, went to school in the morning, never turned down a drink, and somehow graduated, starting my first job in journalism for $225 a week. I had been working nights at 3M, had risen to supervisor, and was making over $500 a week. Thus was my first lesson in what kind of a sacrifice it took to be a journalist. That, and having to sell my 1977 Pontiac Trans-Am, with its 6.6 T/A engine and Hurst T-tops, and my red 1970 Jeep J10. And my 1956 pink and white Mercury. And my 1958 Ford pickup that I had painted silver with spray cans, which was unfortunately not the last vehicle I painted drunk. At night. My dad gave me a 1972 Plymouth Duster with the 225 cubic-inch slant-six to drive. Humiliation complete.

What does Yates have to do with this?

Before I even got my drivers license, I was reading Car and Driver, where Yates and William Jeanes and Jean Lindamood and Steve Smith (Lindamood referred to me in a story as “the other Steve Smith,” so now I get to call him “the other Steve Smith”) were busy pointing out that you could be a damn good writer and make a living writing about cars and have fun.

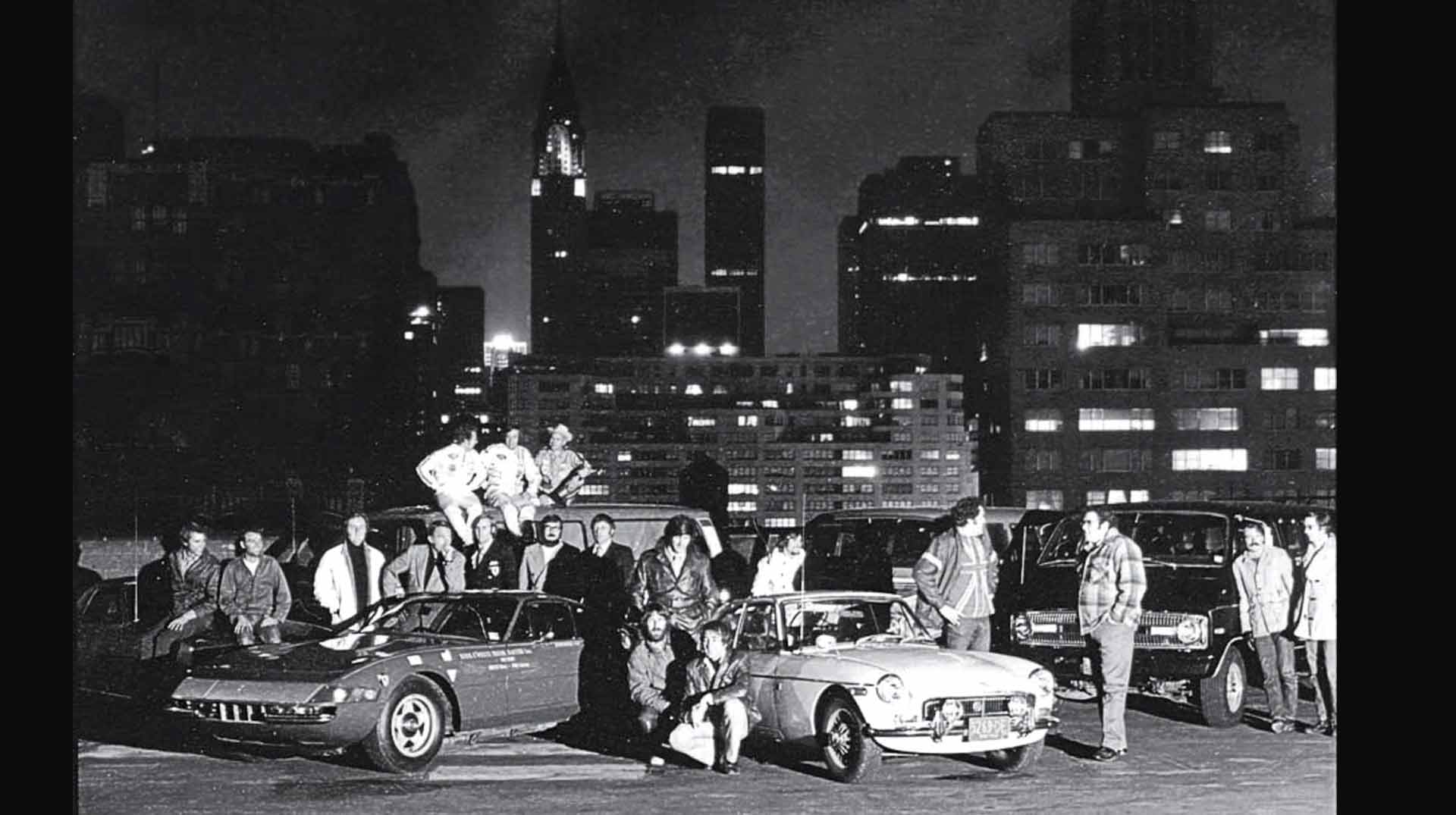

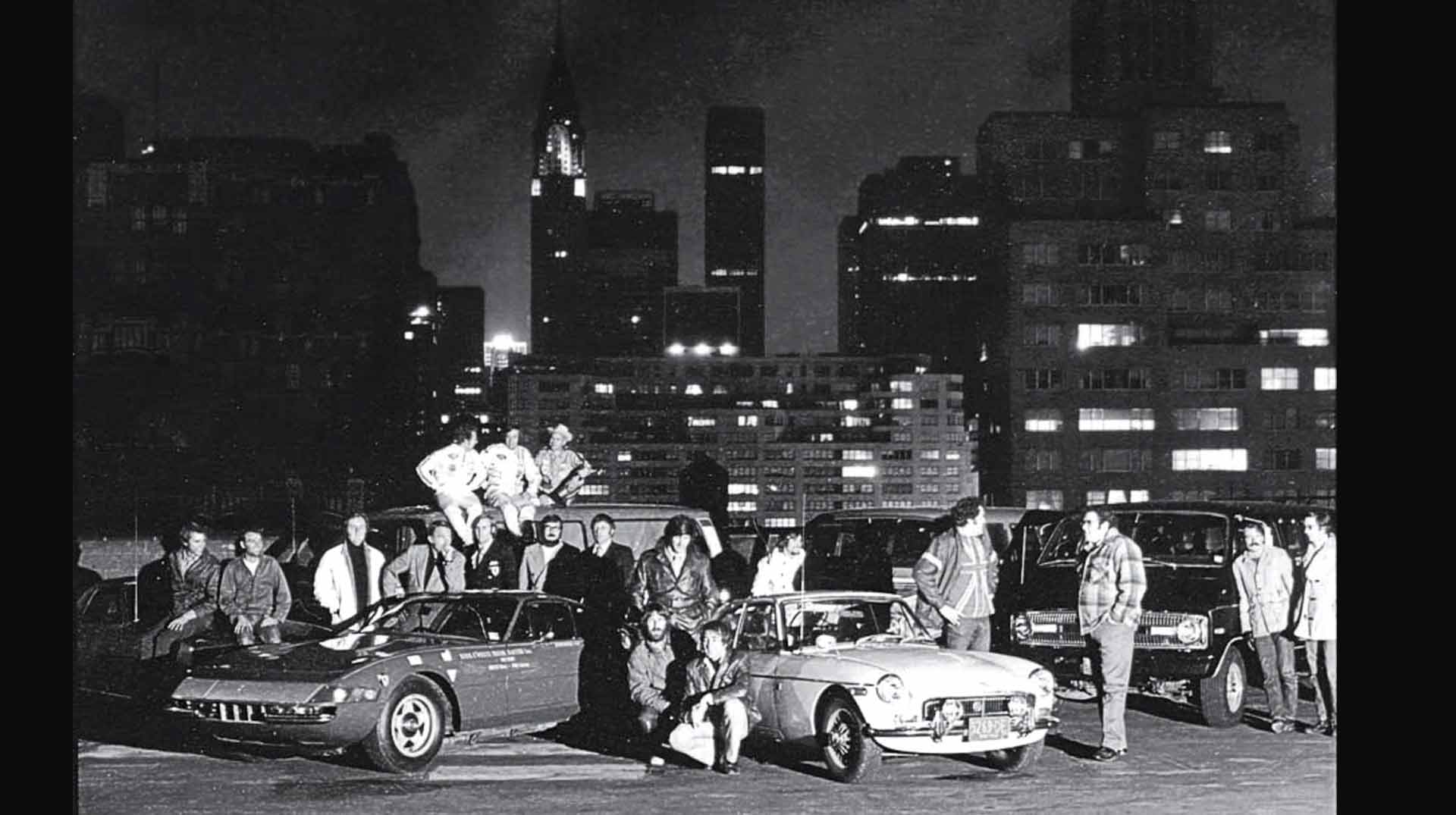

So, 10 years, three newspapers and one public relations job later, I was at the Dallas newspaper interviewing Brock about One Lap of America, the less sinister, more tiring spinoff of his Cannonball Run, which you already know about. Yates had organized a One Lap in 1984 that was sort of a practice run for 1985, when it would be big. Huge. Seventy-five (it turned out to be more) vehicles would leave the Renaissance Center in downtown Detroit, and would essentially make one lap of America.

March 1, leave Detroit, hit Portland, Oregon on March 3; turn left, drive to Redondo Beach, California on March 4, where we would overnight at the Portofino Inn. Turn left, pass through Las Vegas, down to Terlingua, Texas March 6, zip up to the Alamo, then through Louisiana to Brumos Porsche in Jacksonville, Florida, March 8. Up to the Lock, Stock and Barrel, a bar in Darien, Connecticut where some of the Cannonball Runs began. Then a left turn back to the RenCen in Detroit, arriving March 9. It was, as I recall, close to 11,000 miles, with all the time spent inside the vehicle, except for that one night in Redondo Beach at the Portofino.

Interesting, I said. How might a man get a ride in such an event?

Yates made a call to Bill Baker, who was doing some public relations for Chrysler, then went on to introduce Range Rover to America. Suddenly I was in a brand-new (then) Dodge Caravan “minivan,” they called it, with Ben Farnsworth, a CBS Radio reporter from New York, and Bobby Burns, a student who was a friend and neighbor of Baker’s. The Dallas newspaper agreed to let me do a three-part series that would go out on the news wire.

We got to Detroit a couple of days early to outfit the Caravan, which fortunately had the “big” engine – a 2.6-liter Mitsubishi four-cylinder, instead of the 2.2-liter Chrysler. I was responsible for the horrible decision to pull out all the seats but the front two: I figured the third person would have more room to stretch out and sleep in back, while his two co-drivers sat up front. But with nothing to tie you down, whoever was in back rolled from side to side like a bowling ball on every turn. Or worse: I’d sit back there and try to type on my Radio Shack TRS-80 “computer,” before attempting to hook it up to some gas station pay phone to send it back to the paper.

A highlight: Our Chrysler team car was a Le Baron Turbo. One of their guys needed to visit an auto parts store, and I volunteered to drive him. Which is how Phil Hill, the only American driver to win a Formula 1 championship, got chauffeured around Detroit in the right seat of a Chrysler minivan. “How was my driving?” I asked. “Excellent, since you didn’t hit anything,” he said.

Since One Lap was technically a TSD – Time, Speed, Distance rally – with a bunch of checkpoints around the country, we had installed a mechanical odometer and timer to help us meet the dictated average speed and time. That was how Yates got One Lap by the watchdogs: The winner wasn’t who got to the end the first (unlike the Cannonball), it was the one who maintained the “legal” average speed of 52 mph best. It was a joke: Everybody drove as fast as they could between checkpoints, in hopes you’d have time to gas up and grab a burger.

One watchdog didn’t buy it: Ralph Nader, Yates’ lifelong Professor Moriarty. Nader was outraged by this affront to the public: He sought a court order, enlisted former National Highway and Traffic Safety Administration chief Joan Claybrook, who complained to a Senate subcommittee, and appealed to state and local authorities to come to their senses and shut One Lap down.

Lacking that, he threatened to deliver a busload of crippled traffic accident victims in wheelchairs to block the road. Yates was apoplectic. Cannonball had required no planning, little organization, and sought no advance publicity. One Lap required dozens of people to plan and man the route, and he had sponsors to deal with. Those sponsors became nervous. Suppose somebody T-bones a van full of nuns?

Typical of many writers, Yates was not a detail man; having all these people pay a lot of money to do One Lap, and face the very real possibility that Nader could shut him down, was infuriating and potentially embarrassing on so many levels I was afraid Brock would implode. But it didn’t happen.

In typical Yates in-your-face fashion, he supplied his own accident victim in a wheelchair to flag off each car: Drag racer Shirley Muldowney, in her first public appearance after her near-fatal 1984 Top Fuel crash that crushed her hands, pelvis, and legs.

I’m not sure if Nader and Claybrook made any more noise: After we got the green flag from Muldowney, for the next nine days, every Kardashian in the world could have disappeared from the face of the earth and we wouldn’t have known it. Bill Baker managed to score us a radio-telephone, which allowed us to try to ring some operator atop a nearby mountain to relay our calls, and a “cell phone,” which none of us had ever seen before, but worked in like three cities in America then.

This was really a problem for Farnsworth, who had been told he would have phone service so he would be able to file his daily “Farnsworth Files” back to the radio station from the road. He’d manage to find a connection, and get almost to the end of his dispatch, and we’d drive under a bridge. We’d hear: “…and this is Ben Farnsworth, somewhere in North Dakota, for the Farnsworth Fi…. Shit!” Then he’d try to re-connect with Mabel, who we pictured sitting in a little windowless room atop Mount Pisgah, and file his story again. We even pictured Mabel listening in, and hitting “disconnect,” just because she was so bored and hated her job.

The worst part of the trip came early, as a blizzard was hitting Montana just as we were passing through. No one was on the road, because as we learned later the road had been shut down minutes after we got through, stranding half the One Lap competitors at some truck stop. I drove for hours, at speeds far faster than were prudent, just guessing where the pavement was because everything was white. Once an Audi Quattro flew by – inside was rally ace Ty Holmquist and Car and Driver’s Jean Lindamood. We spoke briefly on the CB radio. I tried to follow in Holmquist’s tracks, but no way could a scared Texan in a minivan match Holmquist in a Quattro. When their taillights disappeared I got really lonesome.

Eventually we got to Portland, then Los Angeles, when we checked into the Portofino for our only night in a bed. Have you ever been too tired to sleep? Yeah. I think there may have been some sort of dinner and breakfast, and it was back on the road, headed for Las Vegas, and as far south in Texas as you can go, and Louisiana Mississippi Alabama Florida Georgia Virginia, where radar detectors are illegal and I made Burns sit in the front passenger seat, put my radar detector inside his baseball cap, and lean forward. Worked. When his head beeped, I slowed down. Then north to Connecticut and left to Detroit, where we checked into the Ren Cen hotel and I got lost in the world’s most confusing building and wanted to cry. And then there was another dinner where we all swore we would never do this again. Then back home and a week later, we were looking for a ride for next year. I did maybe five One Laps before Tony Swan took over the beat, and he was welcome to it by then.

The whole thing was so Brock Yates: Bold, ambitious, hopelessly disorganized, somehow successful thanks to the pluck of the competitors, where we saw some of the most innovative on-the-fly fixes ever. Who would have thought that when the transmission in your S-10 Blazer was leaking out all its fluid, to re-route the windshield washer hose to opening of the transmission filler, pour transmission fluid in the washer reservoir, and when the trans started slipping, just hit the windshield washer button to squirt some fluid into the transmission? Kept them going for another thousand miles or so. This was also the One Lap where a team left a member at the gas station by accident, causing the stranded teammate, who was on crutches, to hitchhike to the local airport and charter a plane to fly him to the next checkpoint. And where Benihana Restaurant founder Rocky Aoki competed in his 1959 Rolls-Royce, equipped, as I recall, with a microwave so he could enjoy tasty Benihana frozen dinners while stranded by the road, waiting on a wrecker. Later he moved to a stretch Volkswagen Beetle limo.

Worth noting: Our Dodge Caravan performed flawlessly. The Dodge people were not amused when we made a quick detour to Pep Boys in Redondo Beach for curb feelers, fuzzy dice, stick-on TURBO badging, custom pinstripe tape and maybe a spoiler, I can’t remember. We finished 17th out of 77 entries, despite the fact that our fancy TSD computer crapped out in the first 10 miles, forcing Burns, the only one of us who could do math, to figure things out using my little solar-powered calculator, with a tiny flashlight taped to the solar part to make it work. Rally champions John Buffum and Tom Grimshaw won, which was appropriate. Fourth was a Mercury Topaz, which was the only time I actually felt good about also owning a Mercury Topaz back home.

In the end, Brock looked even more exhausted than we did. Every One Lap after that went more smoothly, and I think he realized that if his idea could survive this one, he was onto something.

That was the start of my automotive journalism career. Within two years I had stories in AutoWeek, and a year later, in Car and Driver. And I realized yeah, you can have fun in journalism, if you write about cars. And I owe Brock Yates for teaching me that.

RIP, my friend.