NASCAR’s at it again. Faced with a shrinking audience and an on-track product alternatively criticized for staleness and confusing new format changes, the organization is taking a somewhat radical approach to the 2021 schedule for its top-tier series. We’re not just talking about running Cup cars on a dirt track at Bristol. This year, the traditional short track and superspeedway mix also features a record seven road course dates.

Of those, two are entirely new (Circuit of the Americas and the Indianapolis road course), one represents a return after nearly 70 years (Road America), and two are back on the docket after being canceled last year (Sonoma and Watkins Glen). Daytona and Charlotte (which will feature the hybrid ‘roval’ setup) are the only repeats from the 2020 schedule.

So yes, NASCAR’s at it again. And while it’s easy enough to dismiss the Bristol event as somewhat of a gimmick, the expanded road course complement is something else entirely. The decision to more than triple the number of non-oval contests in 2021 reflects a new emphasis on selling NASCAR to a wider swath of racing enthusiasts—especially those more likely to tune in for something more than a high-speed, three-hour parade of attrition.

The funny thing is, this isn’t the first time NASCAR sought to highlight road racing in an effort to shore up a potentially flagging fan base. In fact, almost forty years ago Cup’s Daytona-based brain trust was on the verge of announcing an entirely new direction for the sport, one that would encompass its traditional roundy-round past while building a fresh future with the next generation of race fans and their fickle demands for turns in both directions.

It was called the Left-Right series. No, really. And it was to even have its own special stocker: the Left-Right car.

California Dreaming

Still a decade or so away from the peak of its massive popularity, the 1980s saw NASCAR feeling its way out from a regional attraction to a sport with serious national pull. Optimistic about growth but treading largely unknown territory for a stock car promotion, series owner Bill France Sr. and his crew of grassroots racers looked at the rest of the country from their southeastern stronghold and began to feel a little nervous.

The crux of the issue? For a promotion that built itself on the backs of 500-mile oval endurance tests, the distinct lack of NASCAR-appropriate racing venues in the western half of America made national expansion seem like a dead end. This was a huge problem, especially given the massive population boom that was filling not just California’s coast, but also states like Arizona and Nevada with transplants eager to escape harsher climes. The weather was a factor for NASCAR, too, which found itself locked out of several states due to winter’s grip for a significant portion of the year.

Things came to a head in 1985 when it looked like Riverside, California, was going to lose its race track. This road course was increasingly threatened by the area’s skyrocketing land values and encroaching housing developments—and it was the only date on NASCAR’s entire schedule that took place anywhere outside its traditional geographic footprint. Scrambling, officials took stock of what racing facilities remained available on the west coast and quickly discovered that almost every appropriately-sized track stretching from Washington on down to Baja was another squiggle of asphalt in the same road course vein as Riverside. Nary a usable oval in sight.

Unwilling to give up its Golden State foothold, NASCAR did something unexpected: it innovated. Rather than force its thundering behemoths onto a smaller stage, it decided to create an entirely new class of car, for a brand new subseries that would offer thrilling racing on street circuits carved out of major cities like a true urban Grand Prix. You know, with left and right turns.

The L-R Car: Smaller, Lighter and Not Quite Better

For an organization that loved to play up its backwoods moonshiner traditions, openly discussing a future that included blasting down metropolitan boulevards like the fancier Indy and F1 operations was a massive conceptual leap. NASCAR did far more than just talk about, too: it created a full development program for a Left-Right car (L-R for short), that would be lighter than the existing stock car formula and far better suited for turning in both directions.

While the above might read like a joke—and the dead-on name makes it irresistible, frankly—Cup engineers and car designers took it quite seriously. Recognizing that 3,700 lbs of Chevy wouldn’t exactly boogie through the 90-degree directional changes dictated by the majority of city streets (let alone flow effectively through sinuous road courses), NASCAR looked at next-step-down silhouettes from Detroit.

These included the Ford Mustang, the Pontiac Sunbird, and the Chevrolet Cavalier, each of which was significantly smaller than the Monte Carlos and Thunderbirds found at Daytona and Talladega. While engine options were undecided at the time, NASCAR intended the L-R cars to accommodate either the existing 600-horsepower V8s found in Cup, or the smaller V6 units driven in the Busch series.

“The idea is that we’ll be able to race anywhere,” NASCAR spokesman Chip Williams said at the time. “With this new car, we’ll be able to go to any city and race or any road course.”

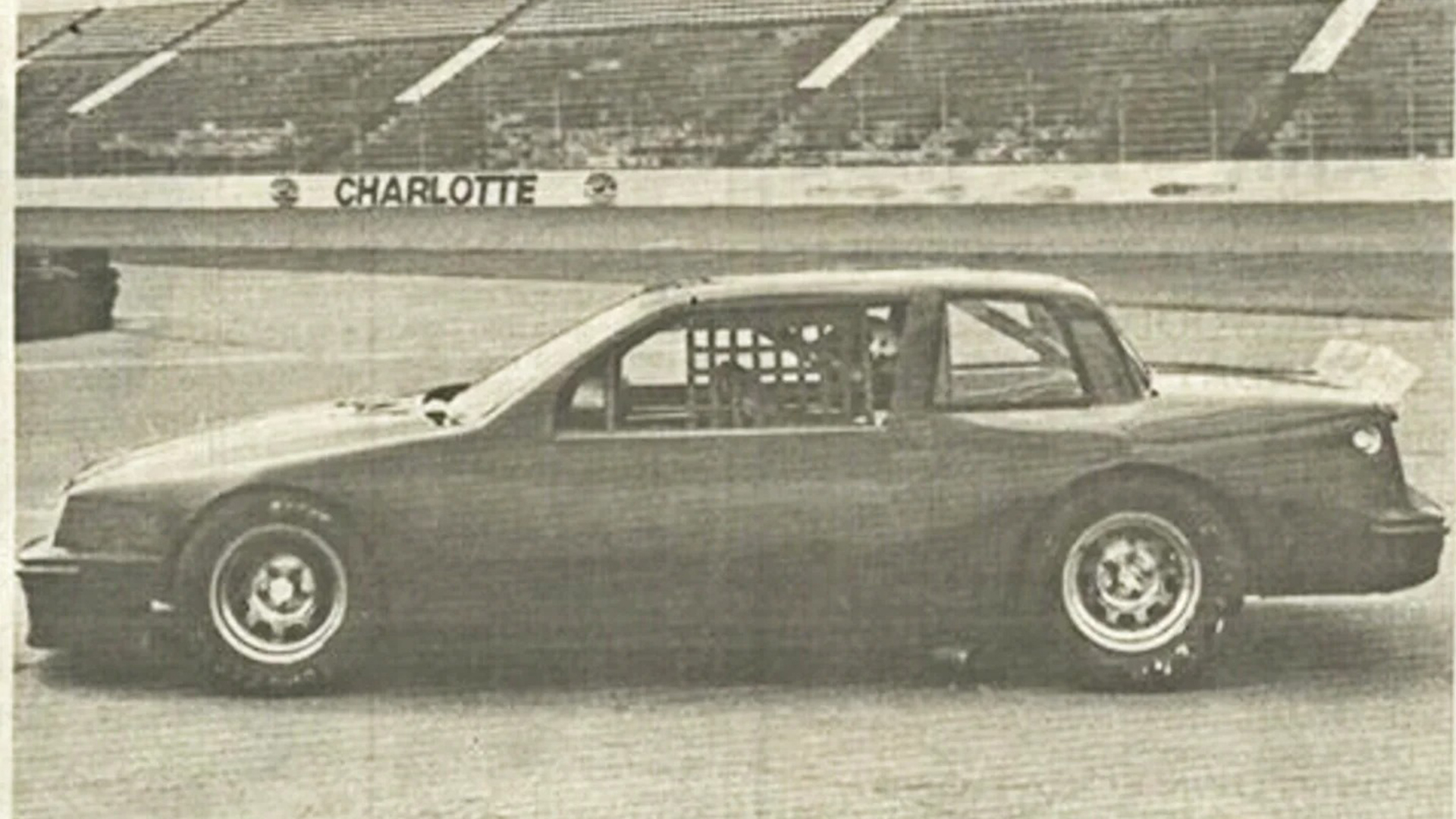

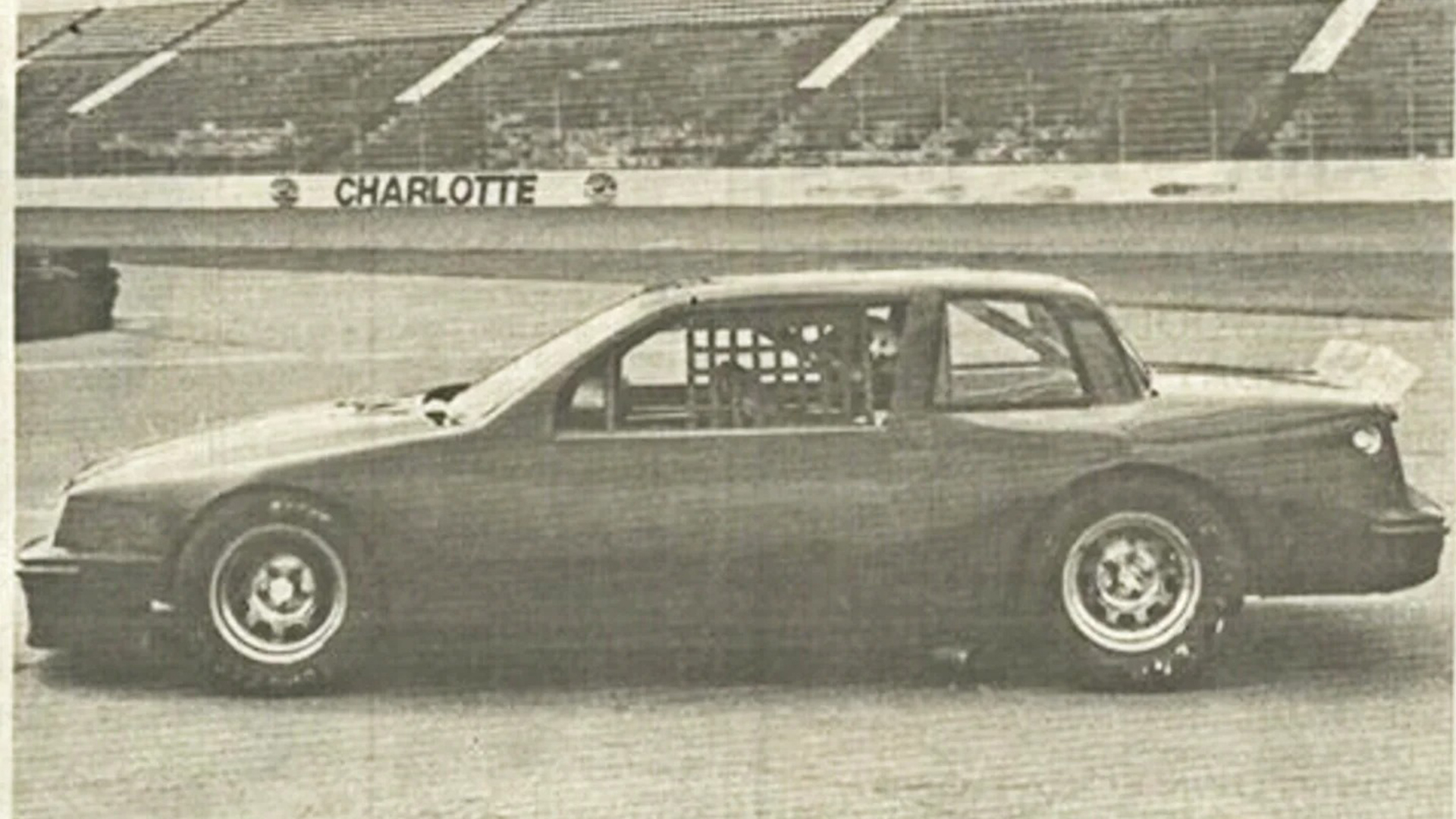

Smaller cars meant less weight, and the initial Pontiac prototype produced by longtime builder Ed ‘Banjo’ Matthews (and tested by Richard Childress Racing) came in at roughly 700 pounds lighter than a traditional stocker. This Sunbird was pushed to the limit by Dale Earnhardt and Bobby Allison in early 1986 on the same Charlotte road-course-oval-track setup that has of late become a NASCAR staple.

Initially, the results weren’t promising. Earnhardt declared the prototype to be unacceptably front-heavy, which gave it unpredictable handling and certainly impacted its mission of topping Cup cars in the curves. Meanwhile, Allison gave this choice quote to a local paper: “Boy that thing went left and right and right and left—on the straightaways. The car is neat and the idea is great, but they need to work on it a little.”

Eight months later, Allison would test an updated V2 Buick Somerset-based L-R car that had been commissioned from Mike Laughlin, another respected chassis developer. Now down to a svelte 2,600 lbs with a slightly longer wheelbase than the Pontiac and a near-perfect front-rear balance, it was almost there. Allison came away from the experience with a much more positive impression of NASCAR’s new program, as you can see in this vintage Inside NASCAR segment from 1986:

Officials seemed to agree, and further highlighted that the degree of parts interchangeability between the L-R program and the Cup cars would help to keep costs down for teams eager to campaign both.

Meanwhile, the hunt was on for venues willing to host as many as five L-R races as early as 1987. “I personally had meetings with and inspected the Oakland Ballpark parking lot. Candlestick Park parking lot in San Francisco. Along the waterfront in San Francisco and I was working with [former San Francisco Mayor] Willie Brown on that who was in favor of doing a big stock car race,” then-NASCAR executive Ken Clapp told Toby Christie. Negotiations were also underway with a long list of traditional road course owners eager to welcome NASCAR dollars, and NASCAR would further test the idea of street courses with a lower-level Winston West event in Tacoma, Washington, in 1986.

The Left-Right Series Lives On in 2021

So why aren’t we all watching spec Camrys and Mustangs haul ass around Laguna and Long Beach? A funny thing happened between NASCAR’s Riverside-related panic and its proposed start date for the Left-Right series: not only did the California road course get a stay of execution that would last all the way through 1988 (several years past what had initially been predicted), but series officials managed to scrounge up a pair of replacement tracks that were perfectly suited to the then-current state of Cup car design.

One of these was a genuine tri-oval located in Phoenix, Arizona, which had agreed to a series of infrastructure upgrades after 10 years of having hosted smaller NASCAR series events, while the other was California’s Sonoma, a wide-open road course then operating as Sears Point Raceway (which made similar facilities improvements). Together, they would expand stock car racing’s reach across the Rockies and help lay the foundations for the sport’s success as more than just a southern spectacle ahead of the 1990s, when things really took off for the sport.

In the midst of this expansion, the L-R series was put aside and largely forgotten. With new dates locked down, having a road course-specific NASCAR operation didn’t feel like a necessity anymore, nor were officials interested in risking the chaos that would result from throwing the wide-hipped Cup cars on a bunch of unfamiliar circuits. It didn’t help that engineering a whole new race car spec for this level of competition was a massive undertaking. NASCAR seems glad to leave the whole concept in the past; you won’t find many mentions of the idea or photos of the test cars in the organization’s official historical literature, and really the most comprehensive online record of it ever existing comes from a great article on racing-reference.info and an accompanying YouTube video. Without those works, the shrinking number of fans who even remember the Left-Right series would surely be smaller.

Only one of the L-R cars ever made it into actual competition, when Bobby Allison hauled the Buick prototype out of storage and self-funded his way into the 1988 24 Hours of Daytona in the GTO class. It failed to finish due to electrical issues.

Although an independent street course program never materialized, NASCAR would regularly make pit stops at Watkins Glen and Sonoma over the next three decades. Some NASCAR drivers turned to the ARCA circuit to brush up on their cornering skills, but by the 1990s the stock car racing began to welcome a steady stream of refugees and dilettantes from the world of sports car and open wheel competition, including future champion Tony Stewart, past Indy 500 winners like Juan Pablo Montoya and Sam Hornish, and of course F1 champ turned soft rock legend Jacques Villeneuve.

Today, the crossover between NASCAR and open wheel goes both ways. Current Cup series title holder Chase Elliott competed in this year’s Rolex 24 for Cadillac, following the footsteps of Kyle Busch, and Jeff Gordon (who won for Cadillac in 2017). It feels only natural that this spirit of cross-pollination will be furthered by NASCAR’s big step into road course racing this year—and it’s impossible not to see the link between the righteous spectacle of Cup cars at COTA in May and yesteryear’s flirtation with full-time ‘left-right’ responsibilities.

Then again, it’s also impossible to avoid the sense that if the Left-Right series had lived, it might’ve given NASCAR another leg to stand on as it’s struggled this century—and the sport could’ve had a running start at figuring out the puzzle that is piecing together a mass audience in today’s world. Time will tell if it’s too little, too late.

Got a tip? Send us a note: tips@thedrive.com